by Asian Geographic Editorial Team

The Malayan Emergency

Following the establishment of the Federation of Malaya, looming uncertainty befell the Chinese majority, who felt excluded from the development and special guarantees of rights given to the Malays, as well as the establishment of a colonial government under the British. This ultimately manifested in the displeasure of the Malayan Communist Party [MCP] (or otherwise officially known as the Communist Party of Malaya [CMP]), which was an organisation that was composed largely of Chinese members committed to achieving an independent, communist Malaya.

MCP was a Marxist-Leninist and anti-imperialist political party that was founded in 1930. They led the resistance effort against the Japanese during WWII, responsible for the creation of both the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army and the Malayan National Liberation Army.

Due to the MCP’s endeavour to fight for Malaya’s independence from the British Empire and establish a socialist economy in its place, there were frequent clashes between MCP and the Commonwealth forces. On June 16, 1948, the MCP launched an attack that led to the deaths of three British plantation managers in the Sungei Sitput district of Perak. That same day, the High Commissioner of the Federation, Sir Edward Gent, declared a state of emergency in several areas in Perak and Johor. The emergency power regulations called for the imposition of the death penalty upon those found in unauthorised possession of firearms, ammunition, or explosives.

In what is known today as the Malayan Emergency, the emergency status was later extended to the whole of Perak and Johor on June 17, 1948, and subsequently the entire Federation of Malaya on June 18, 1948. On June 24, 1948, a state of emergency was also enforced in the Colony of Singapore.

ᐞ British artillery firing on insurgents in the Malayan Jungle, 1955

Forced to flee, the MCP regrouped deep in the Malayan jungles and founded the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the guerrilla army utilized against the British authorities. In attempts to force the British out of Malaya, MNLA launched a series of attacks against soldiers, police, colonial collaborators, and conducted industrial sabotage. Their troops would also destroy rubber plantations and mines in an attempt to harm the British economy as at that time, the British were financially indebted to the Americans and their post-war recovery relied heavily on these plantations.

In the face of intensifying insurgency, British General Sir Harold Briggs developed the Briggs Plan to counter the growing dissent. The Briggs Plan sought to isolate the insurgents by cutting them off from their supporters amongst the population.

Unfortunately, before the plan was finalised, Britain’s High Commissioner in Malaya Sir Edward Gent died in an aeroplane collision. When the emergency reached its peak in 1951 Gent’s replacement, Henry Gurney was assassinated by MNLA members in an ambush against his convoy. Hence, the Briggs Plan only came to fruition when Field Marshall Sir Gerald Templer took over as commissioner.

The next commissioner in line was Gerald Templer, who has to this day, been credited by many historians as being the person who was the most successful in defeating the MNLA.

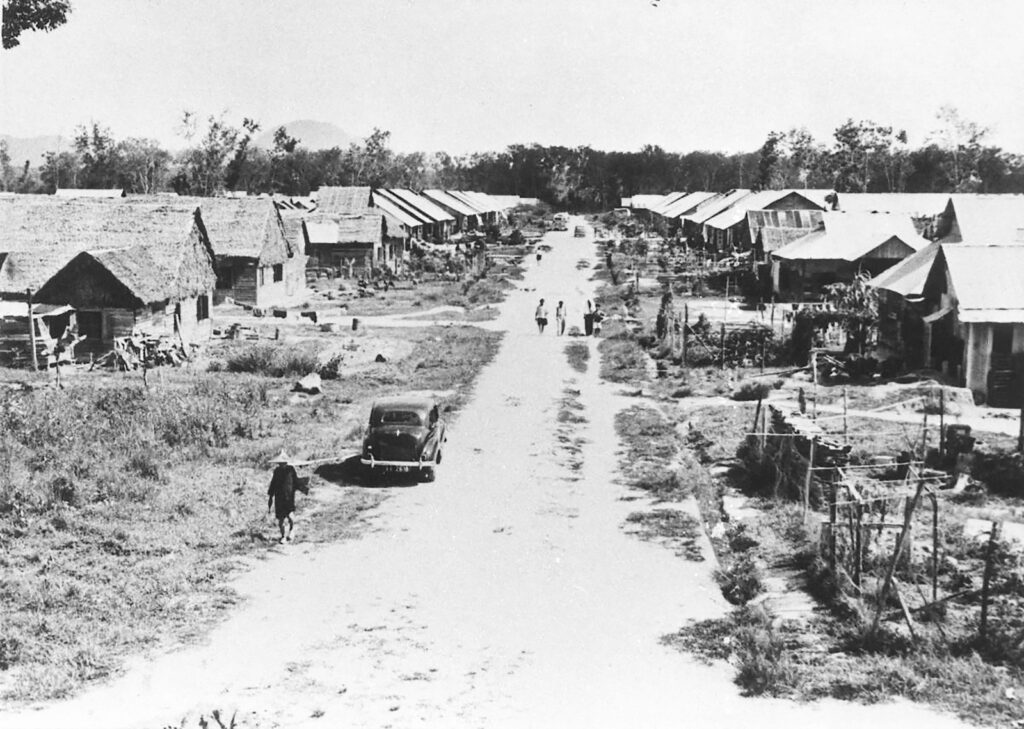

ᐞ A model “New Village” designed as part of the Briggs Plan

Templer oversaw the finalising of the Briggs’ Plan, and though such measures were unpopular amongst the people, its efficacy against the communists could not be denied. Templer constructed new settlements known as “New Villages” and forcibly relocated most of Malaya’s ethnic-Chinese population there. By early 1952, he had successfully moved over 500,000 people (400,000 of them of Chinese majority) from the fringes of the forests into these guarded camps. Additionally, he torched farmlands and sprayed chemical herbicides to destroy the crops in hopes of starving out the communists. A strict food rationing system was also put in place to prevent the Malayan villagers from sharing food with the MNLA.

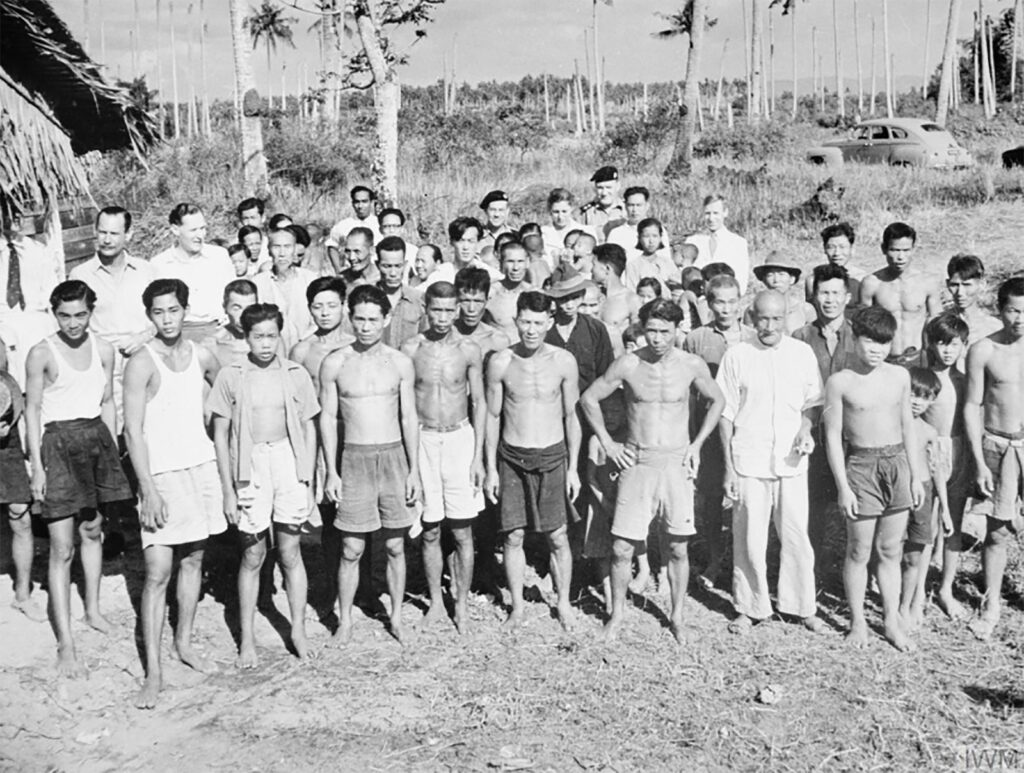

ᐞ Civilians forced to relocate to the “New Villages”

Through the Briggs Plan, Templer and the British military succeeded in separating the MNLA guerrillas from their supporters within the general civilian population. By the mid-1950s, the rebels of the insurgency had been successfully stranded, which severely impacted and impeded the party’s ability to continue fighting.

As the battle against the insurgents raged on, Malaya held its first general elections in July of 1955, seeking to elect members into the Federal Legislative Council. Prior to the elections, members were appointed by the British High Commissioner of Malaya.

The elections were a decisive win for the Alliance (which consisted of the United Malays National Organisation, the Malayan Chinese Association, and Malayan Indian Congress) and led to the formation of a new government with Alliance leader Tunku Abdul Rahman (known simply as “Tunku”) as Chief Minister. Once in power, Tunku was quick to address the ongoing insurgency, declaring partial amnesty for insurgents in exchange for peace. To discuss the terms, Tunku met with communist leaders at Baling on December 28 and 29, 1955.

The Baling talks and Malaya’s independence

After a string of military setbacks, the guerrilla units were forced to retreat to the Malayan-Thai border for refuge. During the Baling talks, the MNLA made several demands, of which the two most notable were that if the MCP were to accept the amnesty, they would be recognized as a legitimate political party in Malaya and that the communist insurgents who accepted the amnesty would not be detained and screened. Tunku initially rejected the two requests.

Refusing to back down, the leader of MCP, Chin Peng, told the Alliance government that the communists would cease their hostilities if the government was able to obtain the powers of internal security and defence from the British government. Chin Peng was under the impression that such a condition was an impossibility and would lead to Tunku’s eventual acceptance of the MNLA’s two requests.

ᐞ Tunku Abdul Rahman at Malaya’s Proclamation of Independence

Tunku broached the topic with the British at the London talks and in an unexpected turn of events, obtained the powers of internal security and defence as well as secured Malaya’s independence from the Crown. The British’s easy acquiescence came down to their desire to end the insurgencies in Malaya. Hence, on August 31, 1957, the Federation of Malaya received full autonomy from the British and the country was finally independent. Tunku Abdul Rahman became Prime Minister

Read more about Malaysia’s History and the lead-up to their separation from Singapore, check out Asian Geographic Magazine Issue 2/2021 coming to the shelves soon or reserve your copy by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com.

Read more about Malaysia’s History and the lead-up to their separation from Singapore, check out Asian Geographic Magazine Issue 2/2021 coming to the shelves soon or reserve your copy by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com.

Subscribe to Asian Geographic Magazine here or for more details, please visit https://www.shop.asiangeo.com/