Back from the beach and behind the terraces of Georgian town houses in the bustling, if windswept, British seaside town of Brighton, is a little piece of India. And China. And a few other places we haven’t quite been able to identify, but certainly owe more to Asia than the south of England. Above the shops and mature trees incongruously poke tapering minarets and fat onion domes, stone fretwork and elaborate finials. Welcome to Brighton Pavilion.

This elaborate, eclectic construction was the pleasure palace of George IV, a regency playboy, prince and, later, king who was known for his extravagant lifestyle, numerous mistresses and, more positively, patronising of the arts. Not satisfied with modernising his existing royal residences of Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, George commissioned the architect John Nash to build for him a folly by the sea where he could escape from the disapproving eyes of London, entertain his secret (and not-so-secret) lovers and host the most flamboyant of parties for fashionable society figures of the day.

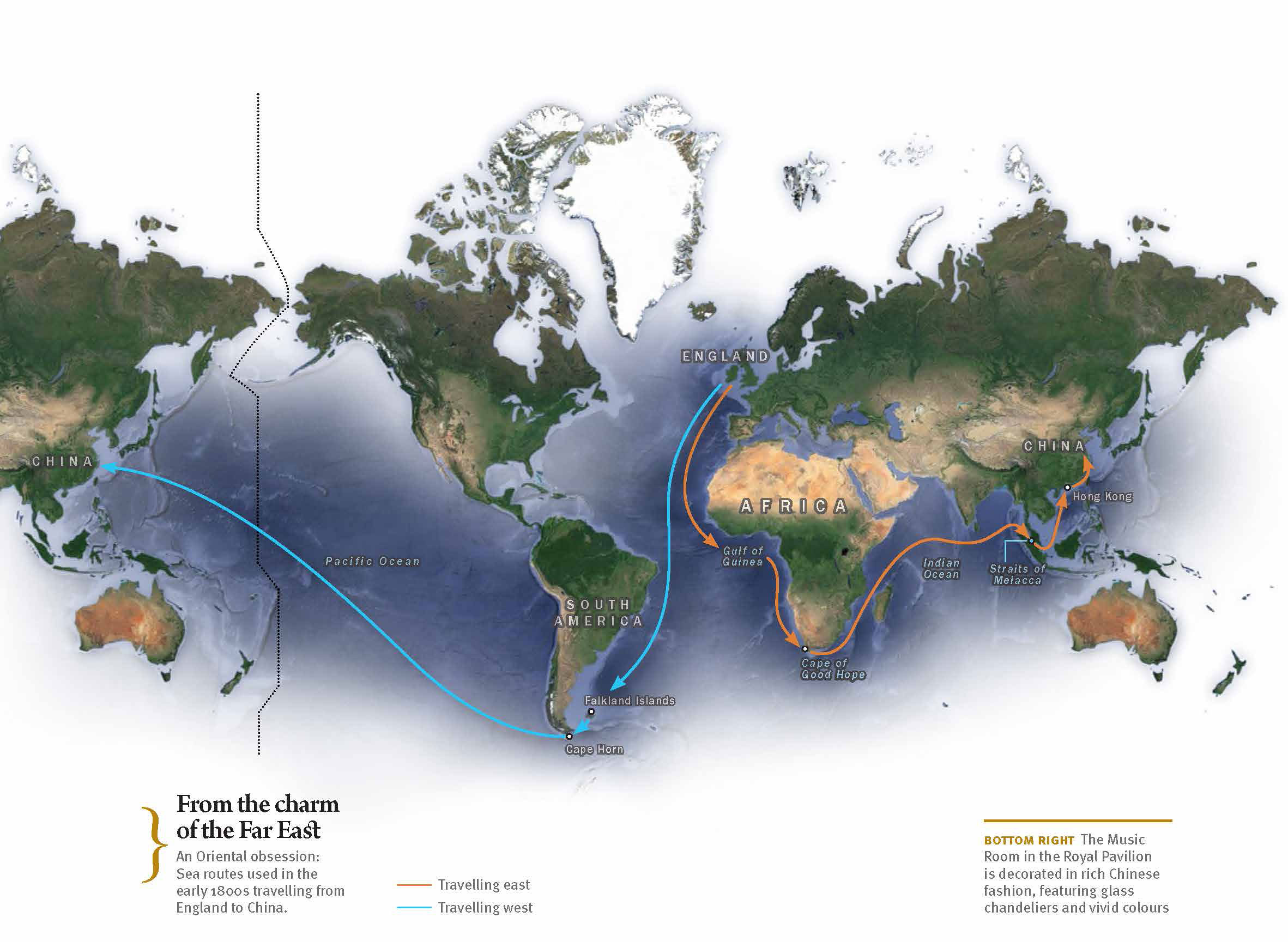

In the early 19th century, George and his contemporaries felt themselves to be at the very centre of the world. Politically, Britain was expanding its influence and territories overseas and the East India Company was shipping back to London the finest goods the world had to offer. “The Orient” – a place few people had actually been, but many dreamed about – was on everyone’s lips. They saw it as a place of unimaginable wealth, where despots in silken robes lounged in harems filled with women wearing nothing but gold and jewels, and where dragons and phoenixes soared above pagodas and elegant gardens. In a rigidly hierarchical society, where etiquette and constraint were prized (unless, of course, you happened to be royal and rich), this mystical, eastern land of hazy geographical location was at once fascinating and horrifying, something everyone wanted a piece of and yet, no one could risk fully embracing.

The solution to the conundrum was Orientalism, a European fashion that took inspiration from the Orient, but gave everything a Western twist so that no one’s expectations (however unrealistic) would be disappointed. Products were made in China specifically to suit European tastes, and back home, artists, designers, furniture makers and all manner of other artisans produced works in an Oriental style. Without a shadow of doubt, the finest and most ostentatious of all these Orientalist creations was Nash’s Royal Pavilion at Brighton.

Visitors today, as when it was first built, step across the threshold of the palace into an octagonal entrance hall, the shape of which was inspired by an Arab’s tent. The pale, green-white walls are the colour of unbleached cotton and, along with the stained glass, feature dragon and serpent motifs. The Orient, after all, encompassed many styles and neither geography nor cultural variation between the countries of Asia would be allowed to interfere in the Orientalists’ dream.

Off the entrance hall is a 50-metre gallery, one of the longest in England. Here the visitor is transported into a Chinese garden, the dusky pink walls reminiscent of the colour of the sky in the half-light before sunset. Greater than life-size plants – a stylised representation of bamboo – decorate the walls, and though the furniture and balustrades might look like bamboo too, they are in fact made from carved beechwood or cast iron, the work of London furniture makers.

Vast curved lanterns with red silk tassels hang from the ceiling to supplement the natural light, fine porcelain (in this case authentic antique pieces imported from China) graces the mantelpiece, and pairs of foo dogs (Chinese guardian lions) and elephant-shaped planters reinforce in the minds of viewers that they have been transported far from home.

Amongst the most curious of pieces in the gallery are the 12 painted “nodders”, 18th-century tin statues of Chinese figures in traditional dress. Made for the export market, they are larger versions of traditional earthquake detectors: the heads are separate from the bodies and so the figures appear to nod when the ground shakes or the wind begins to blow.

These particular pieces were shipped across the world with the heads and bodies separate from one another, for reassembly on site, but what their dispatchers had failed to realise was that the recipients had no way of knowing which head went with which body, un-attuned as they were to the nuances of dress and hairstyle. As a result, the servants at the pavilion did the best they could, not realising that they’d placed male heads atop bodies dressed in female clothing, or the head of a fisherman above a mandarin’s tunic. The bodies retain their mismatched heads to this day.

Amongst the most impressive of the pavilion’s rooms is the banqueting room, where 30 people could sit at the table for dinner with plenty of room to spare. When George IV entertained the Russian Grand Duke Nicolas (later Tsar Nicolas I) here in 1817, the magnificent spread included eight soups, eight fish courses, five platters of vol-au-vents, 40 entrées, eight cuts of wild boar and venison, eight patisseries centrepieces, eight roasted birds, 32 desserts, and 12 rounds of soufflés and fondues.

The banqueting room lies beneath a vast and gilded dome, where gold and silver dragons swoop slightly menacingly around the magnificent crystal chandeliers and its glass, lotus petal-shaped shades. Black and gold murals feature shields with motifs of phoenixes and yet more dragons, and around the room are larger than life size portraits of Chinese figures and scenes: old men with long, white beards; elegant ladies with fans; and children playing in their mother’s skirts. The textiles and accessories might look authentically Chinese, but the facial features of the figures are not: these are the works of European artists and whilst they would have seen and possibly even handled Chinese products, it is unlikely they’d ever have laid eyes on a Chinese person.

The only space that rivals the banqueting room in inspiring awe is the jewel-like music room where the likes of Gioachino Rossini once performed. The blue and gold dome that arches across the room, decorated as it is with 10,000 cockleshells, shimmers like fish scales. Opulent wall paintings stretch from floor to ceiling, their lacquer red background painted with gold landscape scenes above which green-blue serpents and dragons hover, and either sides of the pipe organ pagoda-like roofs top a matching pair of doors. The victim of an arson attack in 1975 and, in 1987, further damage when falling masonry crashed through the roof during a storm, this is probably the most unfortunate of the pavilion’s many rooms, though thankfully it is now fully restored.

Elsewhere in the pavilion, guests may wander through George’s private apartments, and also those of Queen Victoria. The vibrant and exquisite handprinted, and in some cases hand-painted, wall papers that decorate each room are authentic reproductions of those that hung here in the early 19th century, the phoenix motifs, birds, exotic flora and splendid suns as alluring now as they must have been then. Painted screens, inlaid cabinets and desks, and yet more mock bamboo chairs and tables reveal how the Orientalist fashion was not just for show, but penetrated deep into the royals’ private quarters too.

Read the rest of this article in No. 103 Issue 2/2014 of Asian Geographic magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.