Is MSG really that bad for you? We unpack the controversial ingredient thought to produce “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”

Text Alex Campbell

Monosodium glutamate (“MSG”) has gained a somewhat notorious status globally as a foodie villain – a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The Japanese ingredient has been blamed for making people nauseous, even ill, in what has been dubbed“Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (CRS), with symptoms including headaches and asthma.

And yet in most of Asia, it appears that people hold no fear of MSG, which has been credited with the sensation of umami: the fifth taste. In fact, the Japanese have gone so far as to pay public homage to it, in the form of the Yokohama Ramen Museum and Amusement Park. As food critic Jeffrey Steingarten famously challenged in 1999, if MSG is so bad for you, “Why doesn’t everyone in China have a headache?”

Numerous studies have attempted to unpack the connection between the consumption of MSG and the symptoms it is blamed for. Scientific studies have repeatedly shown that MSG is safe at ordinary levels of consumption. And yet, remarkably little is understood in the general public about this food additive: what it is, how it’s used, and why it is controversial.

Related story: Extreme Salt

Related story: The World’s Wee Riches

The story of MSG begins with one Professor Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese chemist at the turn of the century. By 1901, he and his team had illustrated the human tongue, mapping out the locations of our tastes: sweet, sour, bitter and salty. However, Ikeda felt that something was missing – that “taste which is common to asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat but which is not one of the four well-known tastes”. He identified this “fifth taste” by the Japanese word umami, which loosely translates to “savoury”, or, literally, “deliciousness”. He launched a scientific mission to isolate the key ingredient at the heart of this tip-of-your-tongue “deliciousness”.

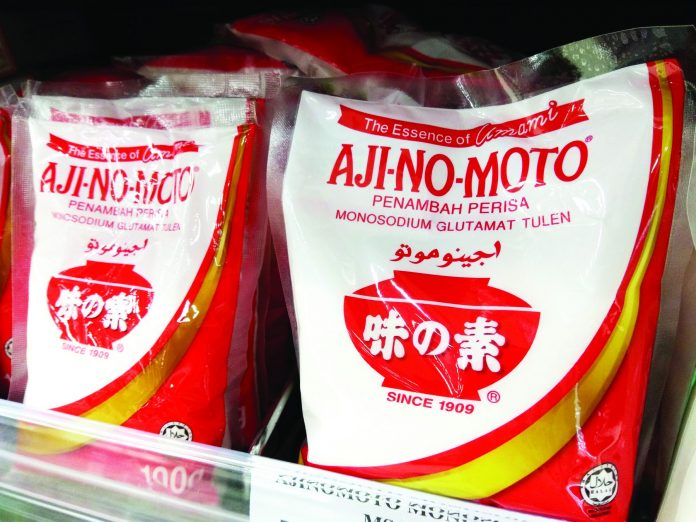

What he found was what we now know as MSG – the sodium salt of glutamic acid. As Ikeda rightly assessed, this occurred naturally in various foods, such as seaweed and shitake mushrooms; it was subsequently also found in human breast milk. Ikeda was able to isolate this ingredient and transformed it into a crystal that could be added to foods where it did not occur naturally. He patented this method, and began selling his brand of MSG, Aji-no-moto, commercially.

The product was a huge success, and within a matter of years, it was being sold all over Asia. By the 1950s, it was in the United States – at a key time, too, as manufacturing processed food was booming.

However, in 1968, Dr Ho Man Kwok wrote a medical op-ed in which he observed: “I have experienced a strange syndrome whenever I have eaten out in a Chinese restaurant… The syndrome, which usually begins 15 to 20 minutes after I have eaten the first dish, lasts for about two hours, without hangover effect. The most prominent symptoms are numbness at the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back, general weakness and palpitations…”.

This launched investigations into MSG and its effects. In 1969, Dr John Olney conducted a study in which he force-fed newborn mice with large doses of MSG, and reported that they suffered brain lesions. A year later, a human study had participants ingest MSG daily for six weeks – but found no adverse reactions. By the 1980s, scientific circles had grown tired of the debate and inconclusive studies. Since then, public organisations – including the United Nations food agencies, the European Union, and several other governments – have declared MSG as perfectly safe.

However, this did little to curb the media storm surrounding the MSG food scare. Russell Blaylock’s book Excitotoxins: The Taste That Kills drove a nail in the proverbial coffin in establishing public opinion as generally anti-MSG. It is still widely accused of causing asthma attacks, migraines, dehydration, chest pains, depression, attention deficit disorder, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, amongst others, although by and large, scientists proclaim this as unsubstantiated. However, there is a group of respected nutritionists who maintain that MSG is responsible for causing behavioural problems in children – but ranks are still divided.

One thing is clear: the controversy surrounding MSG is far from over!

For more stories from this issue, get your copy of Asian Geographic Issue 127, 2017.