Text by Gregg Yan

Like The Hobbit, this tale begins in a hole in the ground.

There is only darkness whether I open my eyes or not – for in this cave of hidden wonders, the sun never shines.

I focus on the pulsing pitter-patter of water droplets, accented by the clicks of bats and the chirps of birds. Staccato sounds echo through the cavern, making it hard to distinguish where the critters are. I try another sense by inhaling. The damp air smells musty and old, but very much alive.

The Philippines has over 3100 known caves. Featuring 12 chambers over its seven-kilometre span, the Langun-Gobingob Cave in Samar is the king of them all. Discovered by Italian Guido Rossi in 1987, it opened to the public in 1990.

“We’re done recording ambient cave sounds. We can turn on our lights and go,” says LUPAD director Nataniel Luperte. Together with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Department of Tourism (DOT), and the LUPAD film crew, our team from the United Nations Development Fund’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (UNDP-BIOFIN) is helping document the largest cave system in the Philippines.

Caves are underground chambers, usually situated in mountains, hills or cliffs. Generations of imaginative fear-mongers have made them the home of everything from treasure-hoarding dragons to a whip-wielding Balrog. In reality, caves are special ecosystems which need our protection, particularly from unscrupulous miners who would break apart tons of rock for a handful of precious stones.

Like waking fireflies, the team slowly activates helmet-mounted headlamps, illuminating an eerie landscape. It’s a mustard mosaic of shapes: Spikes, pillars. and every figure you can imagine. Down here where darkness rules, your mind does a lot of imagining.

Our headlamps barely pierce the darkness, so a powerful superlight is unleashed to gauge just how high the cave is. I estimate it to be at least a hundred feet tall, enough to house a small skyscraper. “There’s an even bigger chamber up ahead, large as a football field,” whispers cave guide Alvin Rafales.

We saddle up and continue wending through a warren of chambers, careful to minimise what we touch to avoid smearing dirt, oil, and acids on the ancient structures. Suddenly, Alvin points to something coiled around a pillar. A menacing, metre-long rat snake. “It hunts birds, not people. It won’t harm us if we leave it alone.”

Unique But Threatened Biodiversity

Samar Island, overshadowed by more popular places like Palawan and Boracay, isn’t usually considered a top tourist destination, owing to its long history as a hotbed for insurgencies and a punching bag for typhoons. Though the Philippines’ third largest island exudes rugged beauty, its real value as an ecotourism destination lies beneath the earth.

“Samar is unique because it is a karst landscape made primarily of limestone. Millions of years of weathering has created numerous caves and sinkholes on the island,” explains Anson Tagtag, head of the Caves, Wetlands and Other Ecosystems Division of the DENR. “Caves are special ecosystems which harbour highly-evolved fauna, most of which have adapted to the dark.”

For instance, the bats flitting around us use echolocation to map out their surroundings. Around us crawl cave crickets, spiders and scorpions. Ahead flow chilly streams teeming with blind cave fish and crabs.

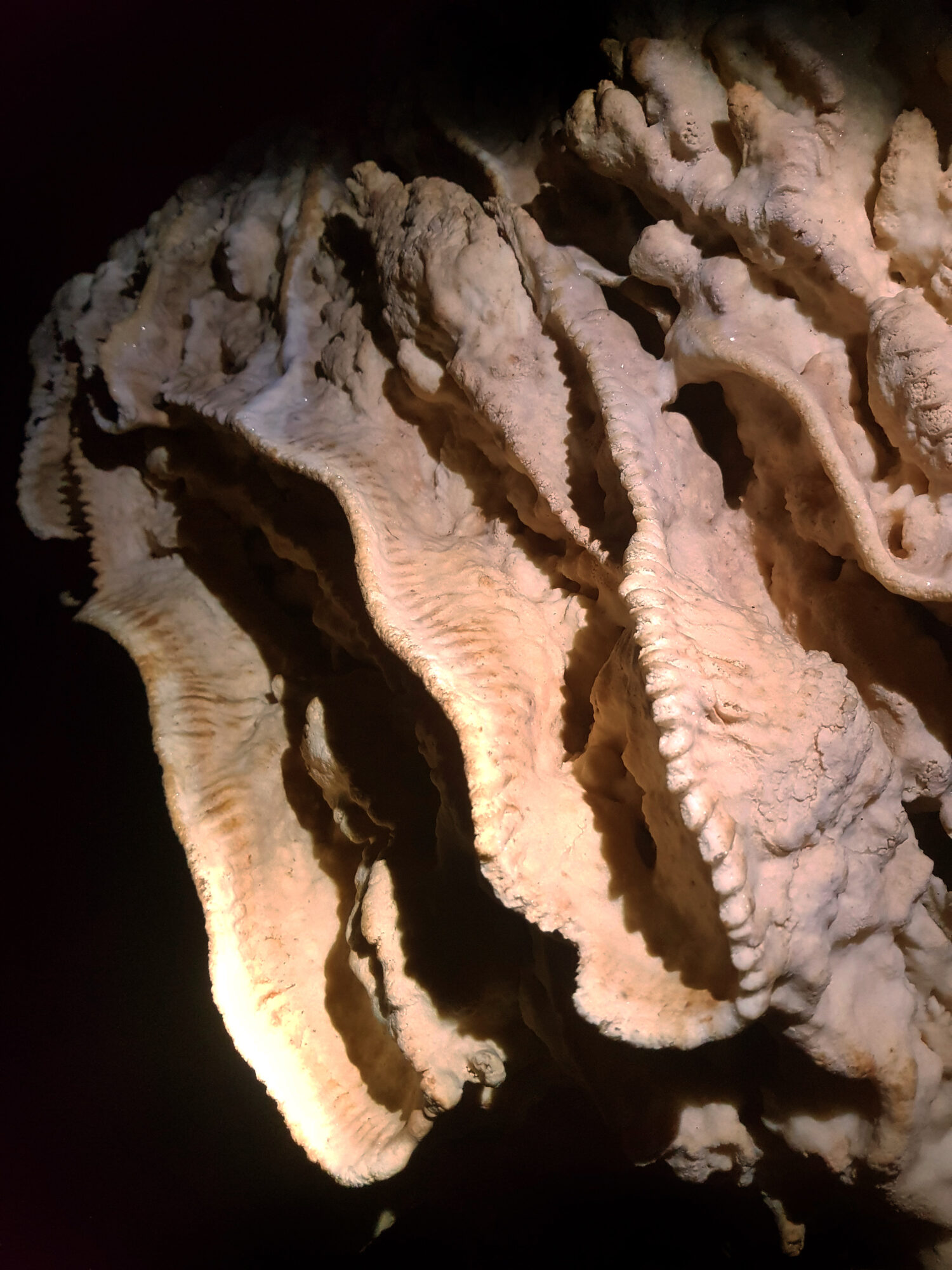

The lack of light confines plants to cave entrances, but mushrooms and other types of fungi cling to life as discreet denizens of dark, damp places.“The speleothems or rocks in caves are in a very real sense ‘alive’ – they just grow and move at timescales difficult for people to comprehend,” explains Dr Allan Gil Fernando, a professor at the National Institute of Geological Sciences in UP Diliman. “The constant dripping of water, for instance, leaves minute traces of minerals like calcite. Over time, these traces pile up to form hanging stalactites and their inverted kin, stalagmites. It takes about a century for a stalactite or stalagmite to grow one inch.”

Judging by their height, some of the cave’s formations look like they started forming long before our species evolved. I’m stunned by the various forms and shapes formed by calcite, aragonite, and other minerals: Having spent quite a bit of time as a SCUBA diver, they looked a lot like coral reefs to me.

Unfortunately, it is because of this surreal beauty that many caves are sundered.

“People used to enter the Langun-Gobingob Cave to break apart and mine stalagmites plus white calcite rocks for collectors,” says Samar Island Natural Park (SINP) Assistant Superintendent Eires Mate. Our guide Alvin confirms this. “Locals used to mine the cave for Taiwanese businessmen, who paid a paltry PHP7 for a kilogram of rock. Balinsasayao or swiftlet nests were plucked out too, to be shipped to Chinese markets.”

The cave was finally declared a protected area in 1997. “Thank God for legal protection. Mining was effectively stopped,” says Eires. The Langun-Gobingob Cave is just one of many natural systems benefiting from the country’s protected area system.

“Declaring key biodiversity sites as protected areas is one of the best ways to ensure that future generations can continue enjoying their beauty,” says UNDP-BIOFIN Manager Anabelle Plantilla. “Visitors should positively support local communities but be mindful of the environmental impacts of their travels. They should, for instance, avoid taking wild plants or leaving trash in tourist sites.”

Year of the Protected Areas

Launched in May 2022, the Year of the Protected Areas or YOPA aims not just to educate people on the need to conserve the 246 protected areas of the Philippines, but to encourage them to visit the sites themselves. YOPA hopes to generate funds from tourists to ensure continued management of protected areas hard-hit by COVID-19 budget cuts.

The Langun-Gobingob Cave is part of the Samar Island Natural Park, one of YOPA’s six highlighted parks, the others being the Bongsanglay Natural Park in Masbate, Apo Reef Natural Park in Occidental Mindoro, Balinsasayao Twin Lakes Natural Park in Negros Oriental, Mt. Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary in Davao Oriental, and Mt. Timpoong Hibok-Hibok Natural Monument in Camiguin.

The country’s caves are now open for tourism, but visitors should know what not to do inside them. “Cave tourism should be well managed and there are cave do’s and don’ts,” says Buddy Acenas from the GAIA Exploration Club, a Manila-based caving and exploration group. “A comprehensive assessment should be conducted before a cave is opened for tourism. Trained guides and set trails should be used to minimise human impacts. Like so many of our fragile wilderness areas, caves must be stewarded by those visiting them.”

For its part, the Philippine government is doing what it can to promote responsible tourism. “Our caves, mountains, beaches, and other protected areas are now open for tourism. We invite both Filipinos and foreigners to come and visit, but to do so in an environmentally-responsible manner,” adds DENR-BMB Director Natividad Bernardino. “By practising responsible and regenerative tourism in PAs, we’re helping our national parks flourish and recover from the economic blow they suffered from the COVID-19 pandemic.” DENR-BMB is the agency mandated to establish and manage terrestrial, coastal, cave, and wetland ecosystems, conserve wildlife, promote ecotourism, and raise awareness of biodiversity conservation.

Forbidden Underground Treasures

Back at the cave, Mon’s superlight illuminates an enormous flowstone, a massive building-sized tower formed by millions of years of mineral deposits. Its base features embedded crystals. As we approach for a closer look, the crystals dance and glitter in the light.

My heart stops not just because they look like diamonds, but because the discovery of precious stones might just spell the end of this cave.

“It’s a good thing no one ever found gold or diamonds in our caves. If someone did, they might tear the caves down. Even I might go crazy looking for precious stones,” joked cave guide Larry Rambacod a few days earlier, when we explored another cave system in Sohoton. He’s right. Even I feel the tiniest inkling of gold fever, of wanting to grab just one shiny crystal. My precious . . . . .

I clear my head and quash the urge.

The dwarves and dragons from The Hobbit were driven mad by their lust for gold, for things that glitter. The irony of the global jewellery industry is that once beautiful swathes of nature are razed for a few scant ounces of metal or crystal, to be worn by the elite at closed-door parties or other social events.

History brims with sad examples: Unending wars spurred by Africa’s blood diamonds, legendary civilisations like the Aztec empire were eradicated for gold, whole mountains hollowed out for cash.

As we ascend back to the cave opening, we see the first rays of light in hours. Muddied but deeply moved by what we experienced, I whisper a quick prayer for the protection of the Langun-Gobingob Cave and the other cave systems of the Philippines. May they stay relatively pristine. And may no one ever, ever find precious jewels in them.

Filipino explorer Gregg Yan braved slithering snakes, scuttling spiders and scented mounds of bat guano for this latest expedition. Catch more of his adventures here!