Text & photos by Sophie Ibbotson & Max-Lovell-Hoare

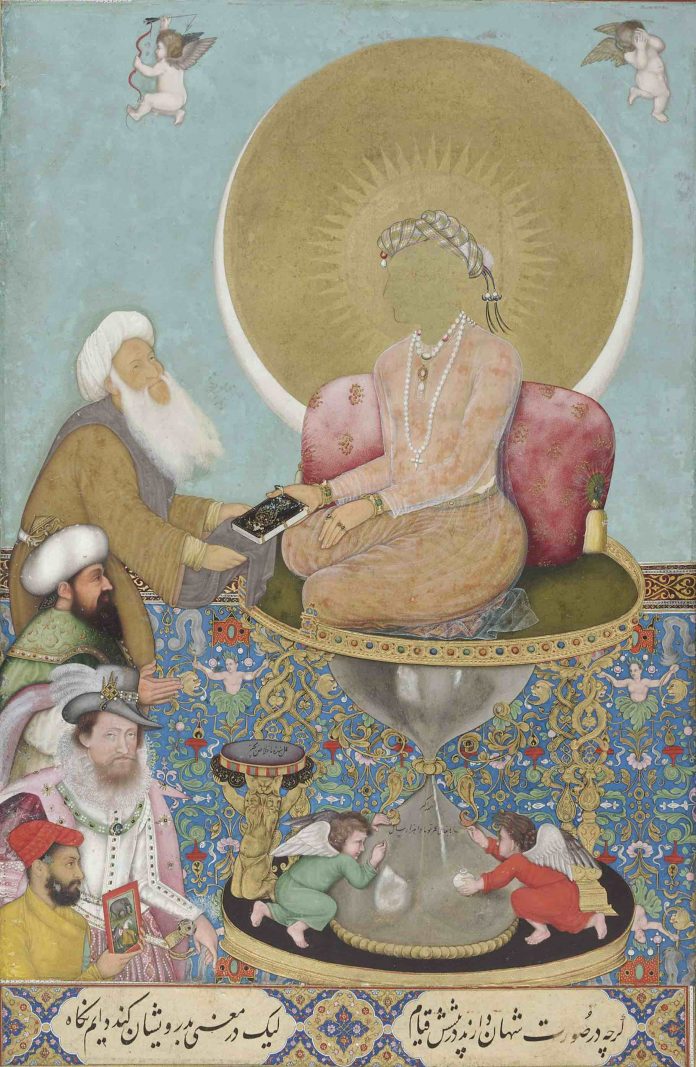

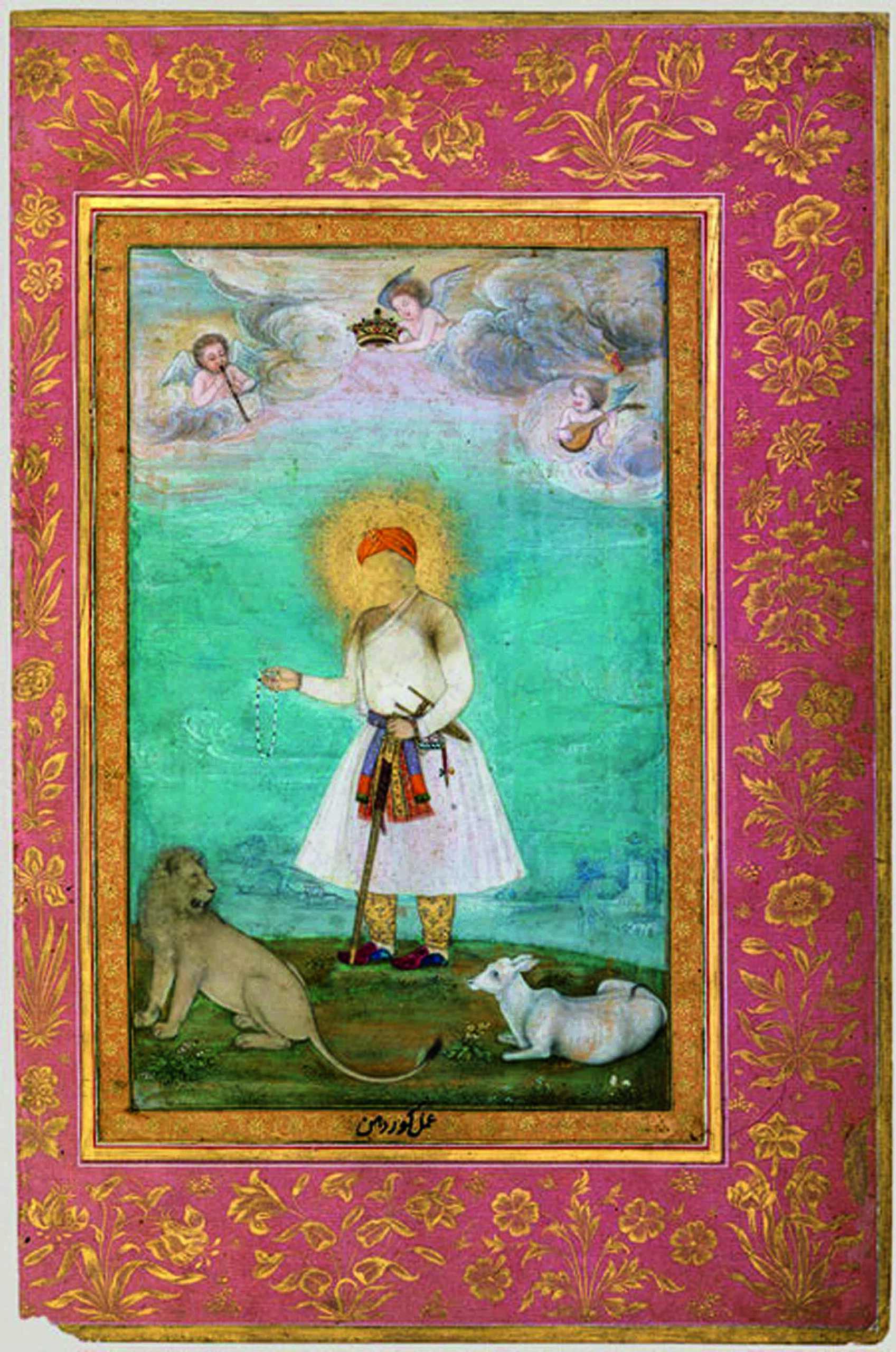

It is often said that Islam does not permit the portrayal of living things in art but, from the earliest days, there have been those who begged to differ. From the Umayyad caliphs to the miniaturists of Persia and India’s Mughal emperors, Muslim patrons and artists alike have experimented with human and divine forms.

Unlike the Christian or Buddhist artistic traditions in which paintings were used to illustrate religious texts, Islam, as a religion, never had a widespread practice of producing and commissioning works of art showing religious subjects. Therefore, when we speak of “Islamic art”, we do not refer specifically to the religion but rather to art patronised and produced by people who shared an Islamic culture.

There is in the Qur’an no explicit ban on creating painted images of God, Prophet Muhammad or of any other living being, but it does prohibit the worship of graven images. The Hadith, the oral traditions relating to the words and deeds of Muhammad, say: “Those who paint pictures would be punished on the Day of Resurrection and it would be said to them: Breathe soul into what you have created.”1 It is therefore from the Hadith and not the Qur’an that the idea that Islam does not permit the portrayal of living things in art comes.

The rejection of figurative art is, however, by no means universal amongst Muslims, with many believing that works depicting living things are acceptable as long as the images do not themselves become objects of worship.

The Umayyad caliphs

The Umayyad caliphate was the second of the four major Arab caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate, meaning “dominion of the successor” in Arabic, was the first system of government established in Islam. It was initially led by the disciples of the Prophet and it represented the political unity of Muslims. The caliph (the head of state) and his officials were to rule over the citizens in accordance with Islamic law.

The Umayyad caliphs’ immediate predecessors in Persia, the pre-Islamic Sassanids (224–651), were keen patrons of the decorative arts, including portraiture and sculpture, and the caliphs followed their traditions. Both empires minted figurative coins to proclaim the identity and sovereignty of the ruler, with new coins being minted when a new emperor came to power.

The British Museum has a particularly interesting collection of coins issued during the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705): not only do we see depictions of the caliph himself, but also apparent representations of the Prophet standing between his companion Abu-Bakri

and wife Aisha. Dating from 693, just 67 years after his death, this may well be the earliest known image of

Prophet Muhammad.

Even in this early period, the depiction of figures was a matter of controversy amongst the Muslim community. A number of clerics voiced their objection to the figurative coins, and consequently they were taken out of circulation and many were destroyed. Abd al-Malik instead introduced a new series of coins where figures were replaced with inscriptions; the name of the caliph and the mint were replaced with Kufic script professing the Islamic faith.

For the rest of this article (Asian Geographic No.81 Issue 4/2011 ) and other stories, check out our past issues here or download a digital copy here