With the establishment of locally managed marine areas around just three of the Mergui Archipelago’s 800 islands, the race to safeguard this jewel of the Andaman Sea faces a long uphill battle

When a nominally civilian government was installed in Myanmar in 2011, and the ensuing years saw the country gradually opening up,

there was cause for optimism. The Southeast Asian nation was hailed as the “last frontier” by foreign business leaders eager to secure a share of a promising emerging market. There was huge potential for investment in infrastructure and manufacturing, a youthful population of 60 million, poised to become consumers, and of course, vast untapped natural resources.

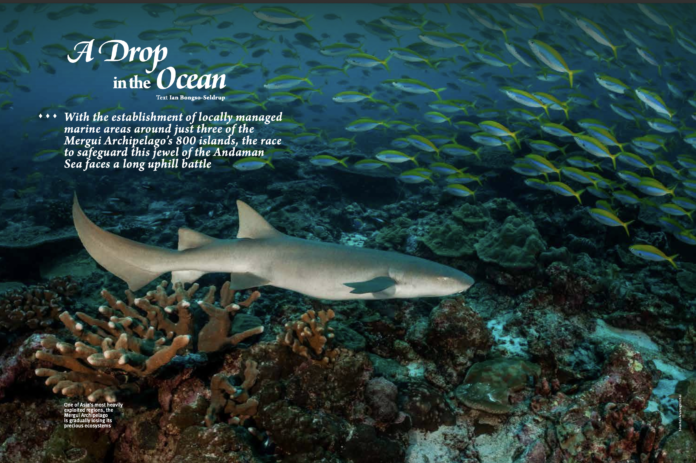

A lucky few had already caught a glimpse of some of these rich natural resources as early as 1997, when the Mergui Archipelago, an immense region comprising hundreds of tropical islands stretched out along Myanmar’s Andaman Sea coast, opened to divers travelling in boats from Thailand. Dozens of world-class dive sites began to be catalogued, including offshore sites such as “Black Rock” and “Western Rocky”. International dive magazines reported bustling reefs festooned with soft corals, abundant fish life, and big animals like sharks and many different species of rays, including mantas.

International dive magazines reported bustling reefs festooned with soft corals, abundant fish life, and big animals like sharks and many different species of rays, including mantas.

The archipelago’s “sea gypsies” – the Moken – completed the idyllic picture. We read about the self-sufficient, nomadic way of life they had led along the Andaman coast for hundreds of years. We learned of their subsistence lifestyle on small, wooden boats, foraging for food using spears – enough to feed their families with a little left over to trade for necessities. Numbering in only the thousands, these seafaring nomads had found a way to live in harmony with the ocean.

Yet this was no “unspoiled paradise” awaiting discovery by the outside world. With the Mergui Archipelago supporting millions of people, principally through direct livelihood benefit as fishers and traders, and as a vital source of

protein, the once-pristine ecosystems were already in decline.

A RELIANCE ON THE SEA

While the majority of islands in the Mergui Archipelago are unpopulated, there are several with sizable settlements and many smaller

villages scattered across the islands. Burmese and Karen ethnic groups predominately occupy these settlements, with their main livelihood being from artisanal fishing, mostly using gill nets.

There are many more artisanal fishers operating out of the small towns and cities dotted along the coast of the mainland, especially Myeik, the largest city in the Tanintharyi Region, which encompasses the Mergui Archipelago (properly called the Myeik Archipelago). According to

one 2015 estimate, there are as many as 8,000 to 10,000 inshore vessels. Moreover, beyond the artisanal fisheries, there is also a sizeable commercial fishing fleet, which uses damaging trawl nets, purse seines, and drift nets among their arsenals.

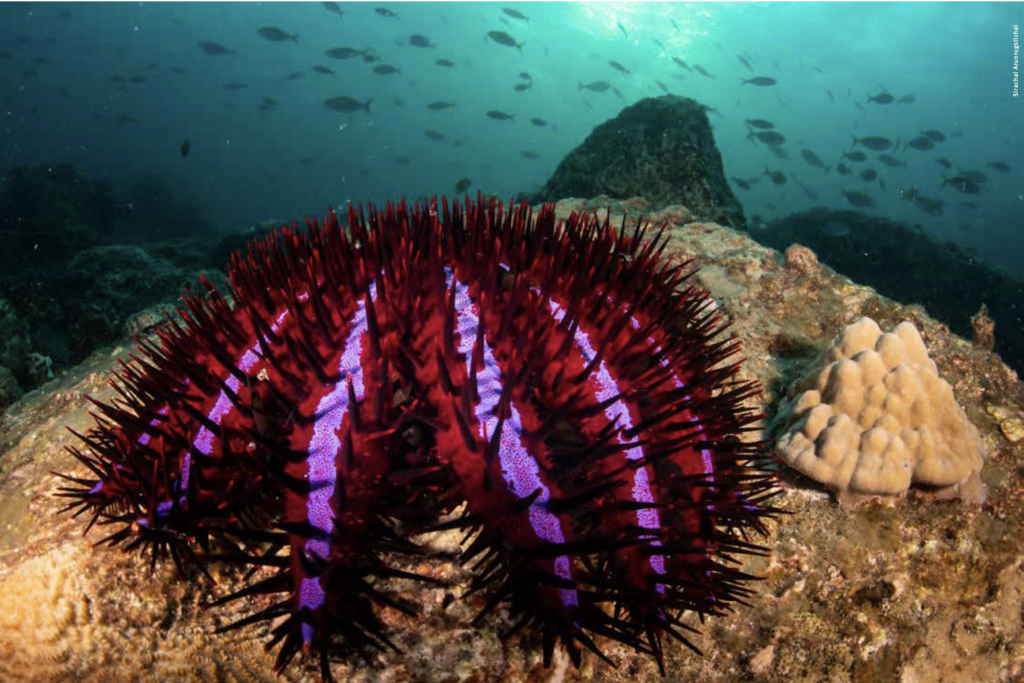

Over the last several decades, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, destructive practices such as blast fishing, and the discarding of fishing nets have all taken a severe toll on this precious marine environment.

Over the last several decades, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, destructive practices such as blast fishing, and the discarding of fishing nets have all taken a severe toll on this precious marine environment.

COMMUNITY-BASED CONSERVATION

Myanmar’s gradual opening up from around 2011 also encouraged non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to begin working

in the country. The largest and most active wildlife conservation charity has been Fauna & Flora (until recently, named Fauna & Flora International), a UK-based organisation with a 120-year history and more than 120 conservation projects across 40 countries.

The charity’s work in the Mergui Archipelago began around 2010, with detailed surveys between 2013 and 2017 aimed at understanding the status of the region’s habitats and species, Sirachai Arunrugstichai and identifying priority areas for protection.

Working with scientists and students from local universities, staff from Myanmar’s Department of Fisheries and Forestry Department, and various international researchers, the Fauna& Flora team conducted in-depth studies of the reefs and their associated fish and invertebrate life, as well as the seagrass beds and the fished species they support.

“We were trained as scientific scuba divers in Thailand,” Zau Lunn from Fauna & Flora’s marine team tells ASIAN Geographic. “Then we trained more staff, from the Department of Fisheries and the Forestry Department. We also trained one scuba diver from the navy. The team dived together to collect the coral data.”

Lunn and his colleagues then organised several workshops to explain the findings to the various stakeholders: local community members, government officials, and members of the Myanmar Fisheries Federation, a non-profit supporting and promoting the fisheries sector. Working together, they identified three areas for protection, designed to operate as locally managed marine areas, or LMMAs.

“When we worked to establish the locally managed marine areas, it was very strange for everybody. Nobody, especially in the community, believed this would become a reality,” says Lunn, explaining that people were only familiar with the “top-down” approach to management;community-led conservation was an alien concept. “They said that it would be impossible, but they worked together, because they knew that fish stocks were declining.”

With the stakeholders on board, despite some remaining scepticism, Lunn and his colleagues eventually submitted their management plan to the Department of Fisheries, and in 2017, Myanmar designated its first three LMMAs – Langann, Done Pale Aw, and Lin Lon. Aiming to protect some of the most species-rich habitats in the archipelago, they promised to enable local communities to play a driving role in the better management and conservation of their surrounding marine areas.

The creation of the LMMAs was an important step in a country that has otherwise designated just a single small marine protected area (MPA), the 200-square-kilometre Lampi Marine National Park, established in 1996, at the southern end of the Mergui Archipelago. The news was celebrated by the conservation community. Having included the archipelago among its list of “Hope Spots” owing to its diversity of species and habitats, Mission Blue, the non-profit marine organisation led by legendary oceanographer Dr. Sylvia Earle, named Fauna & Flora as the Champion of the Mergui Archipelago Hope Spot.

Now, for the freshly appointed community managers of Myanmar’s special new marine areas, the hard work was about to begin. Without enforcement – patrolling the waters to ensure compliance with the rules – the LMMAs could never be effective.

The creation of the LMMAs was an important step in a country that has otherwise designated just a single small marine protected area

With the establishment of the LMMAs, the community agreed to three structures to guide management efforts. Firstly, “no-take zones” meant the total prohibition of fishing activities in important coral or seagrass areas. Secondly, “seasonal closure zones” required areas such as spawning or nursery areas to be protected from fishing during certain critical periods. And thirdly, “gear restriction zones” prevented the use of specific kinds of fishing gear, for example, fishing nets that do not allow juvenile fish

to escape.

In the initial stages, Fauna & Flora supported patrols with a grant to the community for three months. Thereafter, the community members conducted patrols on their own and with the help of staff from the Department of Fisheries. “In Done Pale Aw village [one of the LMMAs], they stopped fishing for four months, and after four months, the fish were flourishing again in that area,” says Lunn, adding that nobody

in the community could believe that the no-take zone worked. “Everybody was very surprised.”

For Fauna & Flora, the community-based approach at the centre of the three established LMMAs is integral to their success, and an expanded system of LMMAs is one of several models that the organisation believes can lead to the creation of an effective MPA network across the Mergui Archipelago.

ENFORCEMENT CHALLENGES

Founded in 2018 – the year after the establishment of the LMMAs – Myanmar Ocean Project has been working in the region to assess the impact of abandoned, lost or discarded commercial and artisanal fishing gear across the archipelago. They conducted six expeditions in 2019, surveying 87 sites over 43 diving days. The main survey areas were Lampi National Marine Park and its surrounding areas, the three LMMAs, and three dive sites previously frequented by divers but subsequently abandoned due to pollution by ghost nets.

Shockingly, the Myanmar Ocean Project team found 95 percent of the sites they surveyed had some form of ghost nets present. Around one-third were classified as “hotspots”, areas deemed to pose a severe threat to coral reefs, marine life, and the livelihood of the community. Here, the team recorded regular intentional discarding of nets by resting boats as well as multiple layers of lost nets covering reefs. During the work, more than 1,800 kilograms of ghost gear was removed and analysed.

Only Lampi National Marine Park revealed less-polluted sites, with moderate and severe levels of ghost gear recorded beyond the designated marine park zone. At High Rock, one of the former dive sites surveyed, the expedition revealed how rapidly – within just two fishing seasons – areas with high fishing boat traffic could become hotspots. The team had already conducted a survey at High Rock three years earlier, in 2016, finding a dive site vibrant with healthy corals, but when they returned in 2019, they discovered multiple layers of ghost nets had accumulated, and a seascape devoid of life.

Most concerningly, of the LMMAs, Langann was found to have an alarming level of pollution with ghost nets: Some 64 percent of the sites surveyed were identified as hotspots, though it should be noted that the sites surveyed included those outside of the designated LMMA as well as those within its boundaries. No hotspots were found at the Lin Lon or Done Pale Aw LMMAs, but every site surveyed had various types of ghost gear.

The Myanmar Ocean Project report detailing the findings, “Abandoned, Lost or otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG) in Myanmar’s Myeik Archipelago”, notes that Langann, which contains two villages with a combined population of around 500 Burmese and Moken people, is “a busy area with a steady stream of boats in the bay and fishermen frequenting the village shops”. They estimate that 50 fishing boats use the bay throughout the day, mostly small-scale fishers using gill nets and squid boats, while the areas outside of the LMMA are often targeted by illegal shark and ray fisheries using larger vessels, including so-called “baby trawlers”.

“Every fisherman interviewed admitted to discarding unusable nets into the water whilethe boat was taking shelter (in and outside the village bay),” states the report, which is authored by Myanmar Ocean Project founder Thanda Ko Gyi. However, discarding nets was not the principal reason behind Langann’s ghost net problem. The interviewees highlighted gear conflict – between illegal baby trawlers and gill net fishing boats – as the main reason for the loss of their nets.

“Lost gear is more deadly due to its size,” Thanda Ko Gyi tells ASIAN Geographic. “These are usually very large pieces of net that engulf the whole reef, entangling marine life and damaging marine biodiversity for years. Discarded gear tends to be smaller pieces, so are less damaging.”

SHARK AND RAY CONSUMPTION AND TRADE IN MYANMAR

Shark fishing has been banned in Myanmar for more than two decades, but there is very little enforcement, while there are no regulations in place to manage ray fishing. Sharks and rays, often endangered, are also commonly taken as bycatch. Many of these fisheries, both legal and illegal, operate in the Tanintharyi Region, which includes the Mergui Archipelago. Shark and rays are consumed across the country, especially in coastal communities, while dried gill rakers and shark fins are traded internationally via wholesalers in Myanmar’s capital, Yangon.

“Shark factories” operate with impunity in the Mergui Archipelago. Thai photographer Sirachai Arunrugstichai tells us that he gained access to the villages processing sharks very easily, even as a foreigner. “They don’t do finning out at sea. They just get the whole sharks and cut them in the factory,” says Arunrugstichai. “But when you are there, it’s more than just about the sharks. It’s about the people, because the workers there are young kids, teenagers, 13 or 14 years old, working so hard. They’re just trying to make a living.”

“Carefully planned and research conservation management is very much needed, but where communities have nowhere else to turn to for income and food, simultaneous effort to lift these communities out of poverty should also be a priority,” says Thanda Ko Gyi from Myanmar Ocean Project, which has studied the shark and ray trade in Rahkine State, further north along the western coast. “I watched a 12-year-old boy process a small mobula ray and his uncle said, “The knife is the only thing we have to learn to use and make a living with. What else are we supposed to do.’”

FINDING SOLUTIONS

Above all else, interactions between the communities of the Mergui Archipelago and non-profits like Fauna & Flora and Myanmar Ocean Project have demonstrated that fishers recognise that fish stocks are indeed declining and that both overfishing and ghost gear are contributing significantly to the problem. There’s a desire to find answers and a willingness to change behaviours. But it’s a complex picture, and there will be no simple remedies.

To tackle the issue of discarded ghost nets, Myanmar Ocean Project is exploring the idea of collection points for end-of-life gear. These could be located within villages where there are good relationships and significant interactions with fishing boats. Another possibility is end-of-life

gear being collected by wholesale or market boats that are interacting with resting fishing boats while selling their goods. “Preventing and

reducing discarding of end-of-life gear should be fairly straight forward, if the country is stable and communities are more engaged,” says Ko Gyi from Myanmar Ocean Project, which has been trialling collection at strategic locations. She notes that their collection trials have been encouraging so far and “fishers have been very keen to be involved”.

A much thornier issue is lost nets due to gear conflict – particularly where it occurs between the local, small-scale fishers and the bigger, often illegal fishing operations. The Langann LMMA and surrounding area, where Myanmar Ocean Project recorded a high concentration of ghost gear, is a case in point. “Those are legal fishing boats, but they fish illegally near the islands,” says Zau Lunn, referring to the bigger boats coming from the mainland. “They are baby trawlers. They fish about two to three miles from the islands. These are coral and seagrass areas where they are not allowed to fish.”

While the establishment of Myanmar’s first three LMMAs should be seen as a victory, it’s clear that the future of the Mergui Archipelago rests on enforcing zoning and the creation of an effective system that allows local fishers to report illegal fishing activities. As long as better regulation and enforcement remain elusive, the valuable habitats and incredible biodiversity of this special region will continue to be imperilled.

Text by Ian Bongso-Seldrup

For more stories from this issue, get a copy of Asian Geographic No.159 or subscribe at https://shop.asiangeo.com