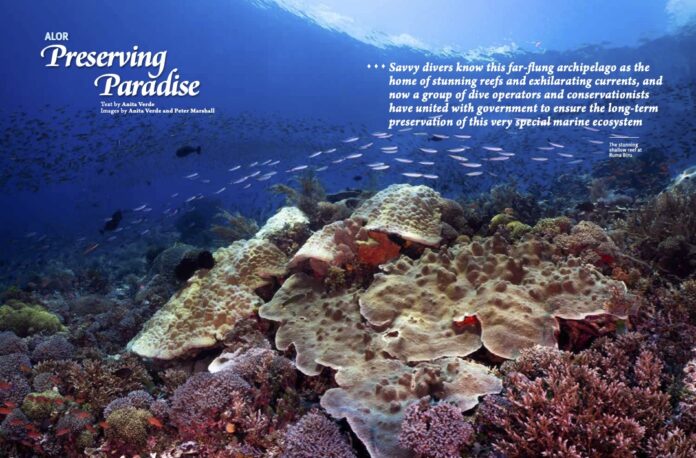

Savvy divers know this far-flung archipelago as the home of stunning reefs and exhilarating currents, and now a group of dive operators and conservationists have united with government to ensure the long-term preservation of this very special marine ecosystem

Against a gilded dawn sky, a reclusive, torpedo-shaped figure bathed in the day’s first light gently breaks the sea’s surface.

The blue whale, the largest animal to have ever existed, is making its way south from its breeding grounds in the Banda Sea, through Alor’s Pantar Strait, passing by Timor on its way down the west coast of Australia, to its feeding grounds in the Antarctic. This is the Alor Archipelago, a wild and beautiful region of Indonesia located to the east of Flores and to the north of Timor, and an important migratory path for more than 20 species of cetaceans.

Diving in Alor is like stumbling across a treasure chest with a kaleidoscope of colours and hidden gems that take your breath away. Boasting over 50 dive sites, with an array of marine life, the reefs are exceptionally healthy, tourism is relatively undeveloped, and the islands are still inhabited by many of the Flores sub-ethnic peoples who preserve their traditional ways of life. Alor has everything: pristine reefs, sharks, whales, dolphins, rare critters, astonishing visibility and adrenaline pumping currents.

Renowned for having some of the more demanding diving in Indonesia, Alor is suitable for experienced divers only. While they keep the reefs in pristine condition and bring a variety of pelagic fish species, the currents can be very challenging, depending on the moon phase. The unpredictability of the currents means you must be experienced enough to be flexible and nimble with your dive plan. Strong currents are also present on the surface, so make sure you bring your SMB, as there are few boats to find you if you were to drift far from your group.

Many of the dive sites are located near local villages, which provides a wonderful up-close encounter into village life. On many dives, you are greeted by children swimming or waving from the shore, or local fishermen with their homemade wooden goggles and spears. If you’re lucky, you’ll encounter a local fisherman freediving to depth to check their bubu, or fishing basket.

THE DIVES THEY ARE A-CHANGING

As we disembark from our Wings Air flight, it appears things here are not as they once were. The tiny airport shed has morphed into a legitimate airport, complete with digital displays and boarding calls. To make our way to our favourite dive resort, the usual two-hour bumpy car journey from the airport to the water’s edge is now a mere 50 minutes along a new, smooth bitumen road.

We are torn as to whether we should tell people about special places like this. This is, in our view, one of the most intact and pristine underwater marine environments in Indonesia. The sheer remoteness makes it special, along with the opportunity to connect with local communities that have a deep affinity with their natural environment. It is far-flung, out of the ordinary, and uncrowded – both on land and underwater.

But now that the airport is bigger and the roads are better, we worry. While these strategic investments are welcomed to support the economic development and prosperity of local communities here, now that the world has awoken from its pandemic slumber, the inevitable future onslaught of visitors to this precious part of Indonesia has the potential to trample the very reasons we choose to come here.

Indonesia is no stranger to mass tourism and its negative impacts are well known and documented. Destinations including Bali, Nusa Penida, the Gili Islands, Komodo and even Raja Ampat are all experiencing it now. Even those that had what they thought were robust marine parks and management models in place are now trying to enact better, stronger and more enforceable sustainable tourism management plans. Sadly, much of the damage in these destinations has already been done and will be difficult to undo. Change takes considerable time, effort, a willing government, and operators committed to following the rules – not swayed by commercial gain.

Luckily for Alor, mass tourism has not yet arrived, but things here are at a crossroads. Pleasingly though, we’re not the only ones concerned about Alor. There is a ground swell, and change is imminent. If government and industry can work together, they just might be able to prevent the marine ecosystem decline seen in so many destinations the world over.

A MASTERPLAN FOR ALOR

Although the Alor marine protected area (MPA) has been in place at a regency level since 2006, it wasn’t until its recent transition to the provincial level that enforcement started to be taken seriously. In 2018, the World Bank offered its support to further develop the MPA to increase economic prosperity in the region. In partnership with the Provincial Ministry of Marine and Fisheries in Kupang, the capital of East Nusa Tenggara, the plan for Alor was to further develop the MPA for tourism, fisheries, and other business areas – on the condition that it would be sustainable.

To support this project, Aliansi Bahari Alor (ABA) (English: Alor Marine Alliance) was established. A partnership between eight local dive operators and the Provincial Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries in Kupang, ABA is currently providing technical advice and partnering in the management of the MPA and the development of a sustainable tourism model for the region – otherwise known as the “Grand Design Masterplan”.

According to ABA President, Frenchman Gilles Brignardello, from Alor Divers, one of the operators championing the project, the principal issue is how the potential future incursion of visitor numbers can be managed in such a delicate ecosystem with challenging dive conditions. “One of the key projects includes a carrying capacity study by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to control the number of marine tourists to the region, and to strengthen regulations in the MPA before irreversible damage occurs to the underwater ecosystem,” he says.

It’s a complex endeavour, to say the least. Everything from diving and snorkelling guidelines, diver behaviour, and rules and regulations for

dive resorts and liveaboards; to better protections across the entire MPA are all being considered. Various other challenging issues also have to be addressed, including reef and fish bombing, cyanide fishing, exploitation and trade of protected marine species, anemone and coral extraction and exports for aquariums, illegal sand mining, depletion of fish stocks, protections for cetaceans and oceanic sharks, pearl farming zones and practices, economic development for local communities, and handling of waste.

The protections being worked up now will hopefully ensure a sustainable tourism model prevails in this region for generations of ocean lovers into the future. But having a comprehensive plan only works if it is implemented effectively through a robust management model that is transparent and accountable.

ENSURING SUCCESS

A local “co-management body” is being put in place to ensure the plan is successfully delivered and the MPA is effectively managed. With a board of representatives from the private sector, government, and NGOs, it will be one of only two examples in Indonesia where a local leadership group is empowered to manage its own MPA.

The board will have the authority to collect the marine park fee when it is implemented in early 2023 (along with other revenue streams), and apply a defined part of these funds for the exclusive purpose of the marine park’s management, ensuring funds get directly to where they are needed with minimal political interference or administrative wastage. While 2022 was a transition period, with a number of projects at various stages, it is expected that the board will begin its role as custodian of the Alor MPA early in 2023.

Illegal, unreported and unregulated activities in the MPA are a serious threat to Alor’s marine environment, so an important element supporting the board’s management of the MPA (aside from the official patrols) will be the Indonesian Government’s existing POKMASWAS programme, which engages local communities in monitoring activities occurring in the MPA. There are currently 11 POKMASWAS groups operating in the 102 villages across the MPA. These “informers” undertake surveillance, monitoring, and recording of illegal activities – collecting and reporting information so that swift enforcement action can be taken.

Key to the programme is the work of the TAKA Foundation, a non-profit organisation engaged in marine conservation. The NGO’s field team is working directly to encourage and empower local communities, in particular women and the younger generation, to stand up, get involved, and call out inappropriate activity in the MPA. TAKA’s Executive Director Maula Nadia says: “The ongoing community capacity building we are doing is integral to both increasing the numbers of POKMASWAS operating in the region, and the effectiveness of the programme overall, particularly in relation to the ongoing management of the MPA.”

THRESHERS ON THE LINE

Alongside migratory cetaceans and pristine coral reefs, aggregations of oceanic sharks such as schooling hammerhead and thresher sharks make Alor’s waters home. Communities here have relied on the local thresher shark population as a food source for more than 50 years, but they are now embracing change as global populations of these animals continue to decline. Thanks to a programme by local NGO Thresher Shark Indonesia, resident fisherman Bapak (Mr) Haji Teibang, no longer fishes for the sharks. “I started fishing thresher sharks in 1975,” he says. “On a good day, I would catch three sharks. They were always plentiful in the sea and I felt blessed when the sea gave us thresher sharks.”

Since 2018, Thresher Shark Indonesia has been gathering data about the presence of thresher sharks in these waters in an effort to transition fishermen from thresher shark fishing to alternative fisheries like tuna. According to Rafid Shidqi, co-founder of Thresher Shark Indonesia, research suggests it is predominately heavily pregnant females that are being caught by fishermen in Alor, particularly in the local fishing grounds inside of Kalabahi Bay. The assumption is that the bay may be a breeding ground for these sharks. Although the evidence for this is inconclusive, it is clear that continuous fishing of the species could be detrimental to sustaining the population into the future – unless this fishing can be stopped.

By providing local fishermen with new boats, engines, and training, Thresher Shark Indonesia has been successful in transitioning nine out of 12 local fishermen from the fishing of these sharks to other species. “Since we began the programme, the thresher shark mortality in Alor has dropped around 50 percent from the baseline,” says Shidqi.

SECURING ALOR’S FUTURE

Pak Saleh, head of the local office of the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries for East Nusa Tenggara, says: “There will be a number of changes for both divers and operators under the Grand Design Masterplan, which will be legislated and included in MPA regulations. There will also be much stronger enforcement of the rules through the POKMASWAS programme and fisheries patrol.”

All divers, snorkellers, and other marine tourists will need to attend a mandatory briefing by MPA officers, pay the marine park fee, and receive a permit before being allowed to undertake their marine activities. Minimum levels of dive experience will be required for both divers and dive guides, and the latter will require special certification to dive in the Alor MPA, over and above their internationally recognised certification.

In addition, resort and liveaboard operations will be regulated in the MPA, and on specific dive sites. Due to their fragility and unique underwater landscapes, a number of iconic dive sites will be closely monitored to prevent damage and overcrowding. On all dive sites, it will be ensured that diver numbers do not exceed the carrying capacity determined by the WWF for each site. There will also be increased protections legislated for coral reefs, turtles, marine mammals, thresher sharks, mangroves, seagrasses, and pelagic fish.

Without question, a comprehensive and sustainable tourism management plan for such an important marine ecosystem is an ambitious task. But there is indeed dedication, commitment, and action being taken by those that can make a difference – simply by choosing to work

together. The protections being put in place in Alor promise to become an exemplar marine ecosystem management model, ensuring both

the continued prosperity of local communities and the preservation of wilderness values for future generations.

PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO ALOR, EAST NUSA TENGGARA

HOW TO GET THERE

Wings Air services Alor’s Mali Airport with direct flights daily from Kupang, with Lion Air connections to the major Indonesian cities of Jakarta and Denpasar, Bali. Kupang is only currently serviced domestically, so transiting through Bali or Jakarta is necessary.

WHEN TO GO

The best time to dive Alor is between April and November. Most dive operators in the area close from mid-December to mid- March. Water temperatures range from 26°C to 29°C year-round, but thermoclines mean temperatures may drop to 20°C or less at certain dive sites.

WHO TO DIVE WITH

Alor Divers (www.alor-divers.com) is a reputable, longstanding dive resort that champions sustainable practices, cultivates environmental awareness, and empowers local communities to protect and preserve local marine life. Nestled amongst the native vegetation on a pristine white sandy beach on the island of Pantar, the resort caters to 16 divers in a selection of standard and deluxe bungalows, each tastefully appointed in the local traditional style and complete with all the comfort divers need. The resort’s dive boats are small, quiet and efficient, adhering to the strictest emissions standards. Water is supplied from the resort’s own underground water reserve.

MORE INFORMATION

Discover how the TAKA Foundation is working to realise the sustainability of marine resources and the welfare of coastal communities in Indonesia, by visiting www. taka.or.id. To find out more about how Thresher Shark Indonesia is protecting endangered pelagic thresher sharks in Alor, go to www.threshershark.id.

Text by Anita Verde

Images by Anita Verde and Peter Marshall

For more stories from this issue, get a copy of Asian Geographic Passport No.156 or subscribe at https://shop.asiangeo.com