Tracing the journey of the “Sea of Light” and the “Light of the Eye” diamonds from a mine in south-central India to a cavernous vault in the capital of Iran

Mention the “Crown Jewels” and you’ll likely immediately conjure in your mind the pomp and ceremony of the British monarchy. In 2023, the world got a rare glimpse of a couple of impressive crowns from the collection on the heads of Charles III and his wife Camilla. The Crown of Queen Mary, worn by the new queen, is notable for having three large diamonds cut from the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found, the Cullinan Diamond.

Of course, the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom aren’t the world’s only collection of royal ceremonial objects. In the regalia of monarchies around the world, there are crown jewels that are equally dazzling and have a fascinating history stretching back centuries. One such example is the Iranian Crown Jewels, properly known as the Iranian National Jewels, which include various elaborate crowns, numerous tiaras, a dozen swords and shields, and a number of unset precious gems. If you’re visiting Iran, you can drop by the Treasury of the National Jewels, situated inside the Central Bank of Iran on Tehran’s Ferdowsi Avenue, and see for yourself some of the most precious bejewelled objects in the world.

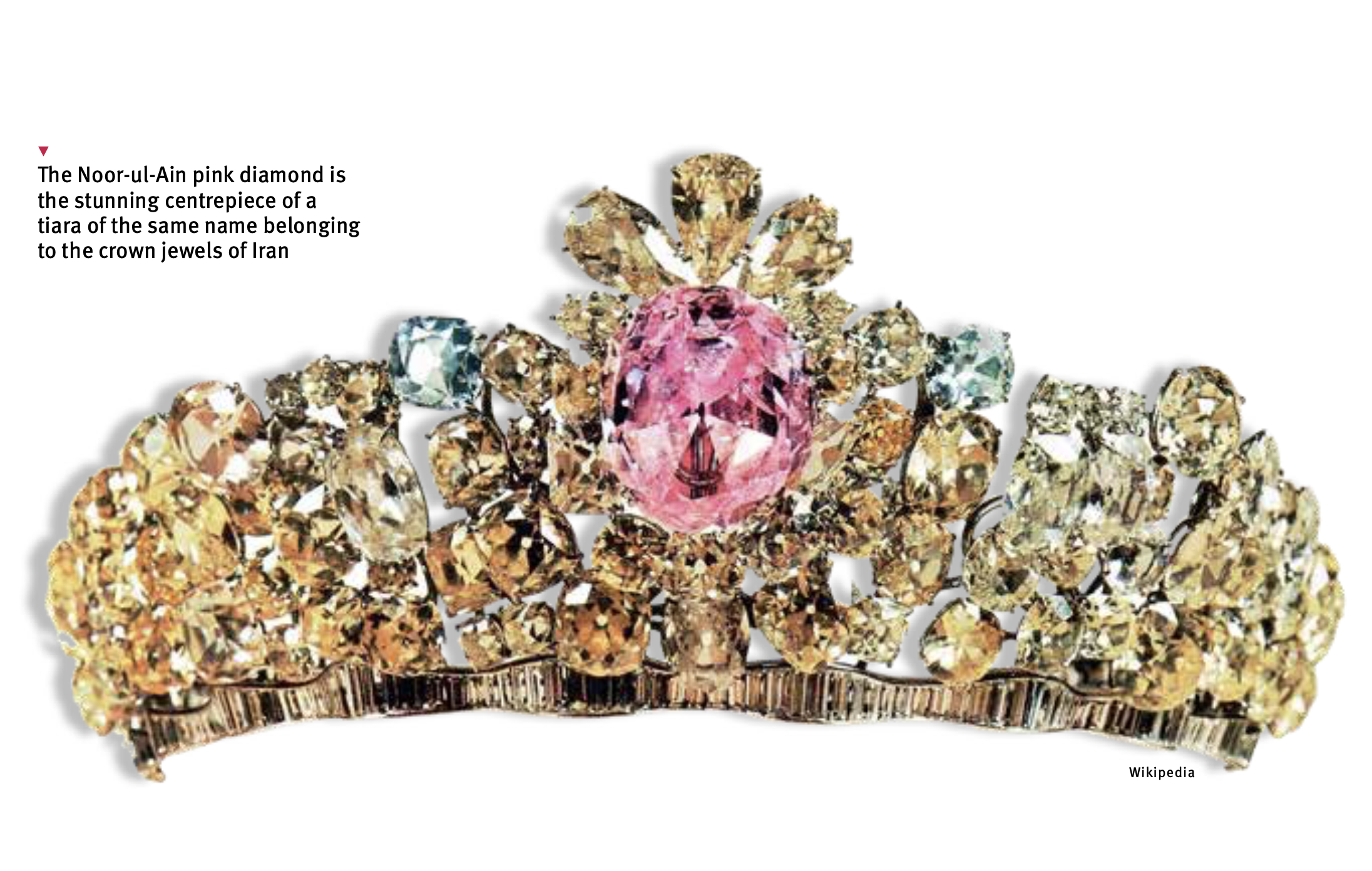

Among the most important of the priceless jewels on display are the Daria-i-Noor, the world’s largest known pink diamond, and another pink diamond, the Noor-ul-Ain, with almost identical colour and clarity. These two storied diamonds are believed to have been cut from the same huge pink stone, named the Great Table diamond, which was once studded in the throne of Shah Jahan, the fifth Muslim emperor of the Mughal Empire.

THE DARIA-I-NOOR

The earliest mention of the diamond named Daria-i-Noor is in a work from the times of Nader Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty

of Iran who ruled as shah of Iran (Persia) from 1736 to 1747. In that work, the stone was listed among the jewels confiscated by Nader during his invasion of India in 1739. As payment for returning the crown of India to the 13th Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah, Nader took possession of the entire treasury of the Mughals. This included the Daria-i-Noor diamond, the fabled Koh-i-Noor diamond, and the Peacock Throne, a splendid jewelled throne that was the seat of the Mughal emperors.

After the assassination of Nader Shah in 1747, the Daria-i-Noor passed into the hands of Alam Khan Arab, one of Nader Shah’s military commanders and the viceroy of Khorasan (1748–54). The diamond, along with other jewels, was then gifted to Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar, later first ruler of Iran from the Qajar dynasty. When Mohammad Hasan Khan was killed in 1759, defeated in battle by the army of the Zands, his political rival, Mohammad Karim Khan (r. 1751–79), the first ruler of the Persia from the Zand dynasty, became the next owner of the Daria-i-Noor.

In 1791, the last monarch from the line of Zand, Lotf Ali Khan (1789–94), desperately needed funds for the fight with the Qajars and planned to sell the Daria-i-Noor abroad with the aid of a British man named Harford Jones, who was engaged, among other things, in the gem trade. Jones advised giving the Daria-i-Noor a brilliant cut to make it more marketable in the West. No such sale ever happened. Instead, in 1794, Lotf Ali Khan decided to send the diamond to Qajar ruler Agha Muhammad Khan, to whom he was losing the war.

Three years later, Agha Muhammad Khan was in possession of the Daria-i-Noor when he was murdered by his servants, who stole the stone and sent it to the Kurdish emir, Sadeq Khan Shaqaqi, hoping to assure protection for themselves. The diamond then journeyed to Azerbaijan when Sadeq Khan decided to contest Fath Ali Shah (1797–1834) for rule over Iran. When he lost the fight for the throne, as a sign of subjection to the new Qajar ruler, Sadeq Khan handed over the Daria-i-Noor. Fath Ali Shah was in possession of the stone until his death in 1834. Legend has it that the Daria-i-Noor was the last object on which the shah gazed on his deathbed.

Later ajar rulers were similarly attached.Naser al-Din Shah (1848-96) believed the Daria-i-Noor had medical and amuletic properties. When he felt weakened after an illness, he had the diamond brought to him, hoping that it would heal him, and he reportedly did not part with it even in the bath. Naser al-Din Shah showed his jewels, including the Daria-i-Noor, to important visitors to Tehran, and he often wore them on his person during travels abroad. He would show off his jewels to visiting European monarchs, who also presented themselves to the shah decorated with diamonds. Britains Queen Victoria was one of the first European monarchs to see the Daria-i-Noor during a display of the Persian Crown Jewels in 1851. She was so impressed by its size and beauty that she even commissioned a painting of the diamond.

By 1931, a change in status of the royal jewels, including the Daria-i-Noor, had begun when they were valued by famous French jewellery firm Boucheron. This allowed the jewels use as collateral for the government’s obligations in connection with the issue of its banknotes. In 1938, the jewels, no longer the private property of the shahs, were transferred to the National Bank of Iran, with the Central Bank of Iran taking over custody in 1960.

NOOR-UL-AIN AND THE GREAT TABLE

In 1642, merchants from Golconda, the capital of the Qutb Shahi kingdom in southern India, offered a pale pink diamond to a famous French diamantaire named Jean-Baptiste Tavernier for 500,000 rupees or about five tonnes of silver coins. Tavernier reported that the stone weighed “176 1/8 mangelins”, equivalent to about 248 carats, and named it “Diamanta Grande Table” – the Great Table diamond.

More than three centuries later, during the reign of the last shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941-1979), Canadian gemologists V.B. Meen and A. Douglas Tushingham examined the treasury of Iran and concluded that the Great Table and the Daria-i-Noor were one and the same stone. The mineralogists further claimed that sometime between 1791 and 1834, the Great Table “suffered an accident”, and as a result, the irregular part was cut off. As it happened, the Iranian treasury contained another smaller pale pink diamond, adorning the wedding tiara of Mohammad Reza’s wife, Farah. The Canadian team was convinced that this diamond – which had an almost identical clarity and colour as the Daria-i-Noor – was likely the remaining part of the Great Table. The diamond, and the tiara in which it is set, is known as the Noor-ul-Ain, or “Light of the Eye”.

According to researcher Anna Malecka, it is highly probable that the Great Table came into the possession of the Indian rulers of the Great Mughal dynasty as early as the 17th century. In 1739, when the Indian subcontinent was invaded by Nader Shah, the contents of Delhi’s treasury were transported back to Iran, and according to historians, the Noor-ul-Ain was among the king’s loot. In other words, the Great Table must have been divided up at the Mughal court before the Persians invaded. Since the Persian occupation of Delhi lasted two months, there would not have been enough time to separate the Great Table, as that would have required at least three months work. This supports the idea that the Mughals cut the major part of the Great Table, the Daria-i-Noor.

According to 19th-century Turkish chronicler Ahmed Cevdet Pasa, when Nader Shah was murdered in 1747, the Noor-ul-Ain was under the supervision of the royal treasurer, and after his death, the stone passed into the possession of various Persian nobles. Cevdet Pasa claims that a visiting Ottoman merchant was informed of the intention of one of these Persian nobles to sell the stone. When the merchant informed the officials of the Ottoman court about the opportunity to acquire the stone, it was brought to Istanbul and presented to Sultan Selim III for inspection. According to Cevdet Pasa, the monarch ordered the purchase of the diamond, for 600 purses of akçe, the chief monetary unit of the Ottoman Empire, and the stone was worked on in the brilliant-cut that was fashionable among the Ottoman elites of the time.

Researcher Anna Malecka says there is no mention of the Noor-ul-Ain in texts referring to the Turkish treasury during the reign of Selim III. But since it is known that the diamond was in the possession of Qajar ruler Fath Ali Shah in 1834, then the Noor-ul-Ain must have been returned to Persia, possibly as a gift from the Ottoman court. Cevdet Pasa notes that Western diamond cutters, considered in the Islamic world to be the great specialists in the art, were employed by Selim III to cut the Noor-ul-Ain. According to researcher Onnik Jamgocyan, envoys of the sultan engaged two French experts, a Parisian named Monsieur Lison and an unnamed cutter, in the 1790s, and it was very likely these men who cut the Noor-ul-Ain.

Without doubt, the intertwined stories of the “Sea of Light” and the “Light of the Eye” diamonds only add to their allure, but we will perhaps never know the full truth behind these precious gems journeys. One thing is certain, however: These stunning pink diamonds deserve to be recognised not just as exquisite gemstones, but also as symbols of Asia’s rich and complex cultural heritage.

The Science of Pink Diamonds

There is some debate in the gemmological world as to how the colour of pink diamonds is formed, but the generally accepted theory is that it is the result of a combination of intense heat and shear pressure, which causes distortions in their crystal lattice. Research has established that these distortions are the source of the colour in 99.5% of pink diamonds, not trace elements, such as nitrogen or boron, which are responsible for creating yellow and blue diamonds, respectively.

Pink diamonds were most commonly found in the Argyle Mine in Kimberley, Western Australia, which produced around 90 percent of all natural pinks in the world. Most of the remainder come from Russian diamond mines. Most Argyle diamonds are classified as Type Ia – in which nitrogen atoms are the main impurity – but they have been found to have low levels of nitrogen, their pink colour instead coming from structural defects of the crystal lattice.

Researchers examining Argyle diamonds have discovered that most are not uniformly pink but have pink zones that alternate with clear areas. According to the scientists, these zones, called twin planes, were formed by some sort of shock, something that happened to them as they were being formed or possibly the result of volcanic activity that propelled the diamonds to the surface. It is thought that certain defects are formed when those twin planes slide back and forth against each other, like a fault plane. They just haven’t been able to figure out the actual atomic structure of the defect causing the pink colour.

Much rarer pink diamonds of Type IIa, which are almost or entirely devoid of impurities, have generally come from India, Brazil, South Africa and Tanzania. It is these diamonds that are thought to have undergone extreme pressure and tension, creating distortions in the crystal structure which lead to the imperfections responsible for the pink colour. The Daria-i-Noor and the Noor-ul-Ain are the most famous examples of Type IIa pink diamonds.

Atomic level distortions in a diamond’s crystal structure through such “plastic deformation” cannot be introduced through laboratory treatment processes, but many colour-producing defects can be created in laboratory-grown pink diamonds. The most common method is irradiating a laboratory- grown diamond with nitrogen impurities, and then subjecting it to high temperatures (600°C to 1000°C). This process creates a defect in the crystal lattice called a nitrogen-vacancy centre that is responsible for the pink colour. Among natural pink diamonds, the ultra-rare Type IIa pink diamonds possess this nitrogen-vacancy centre. In general, natural nitrogen-vacancy pinks have pale colours, while laboratory-grown diamonds have a more intense pink colour.

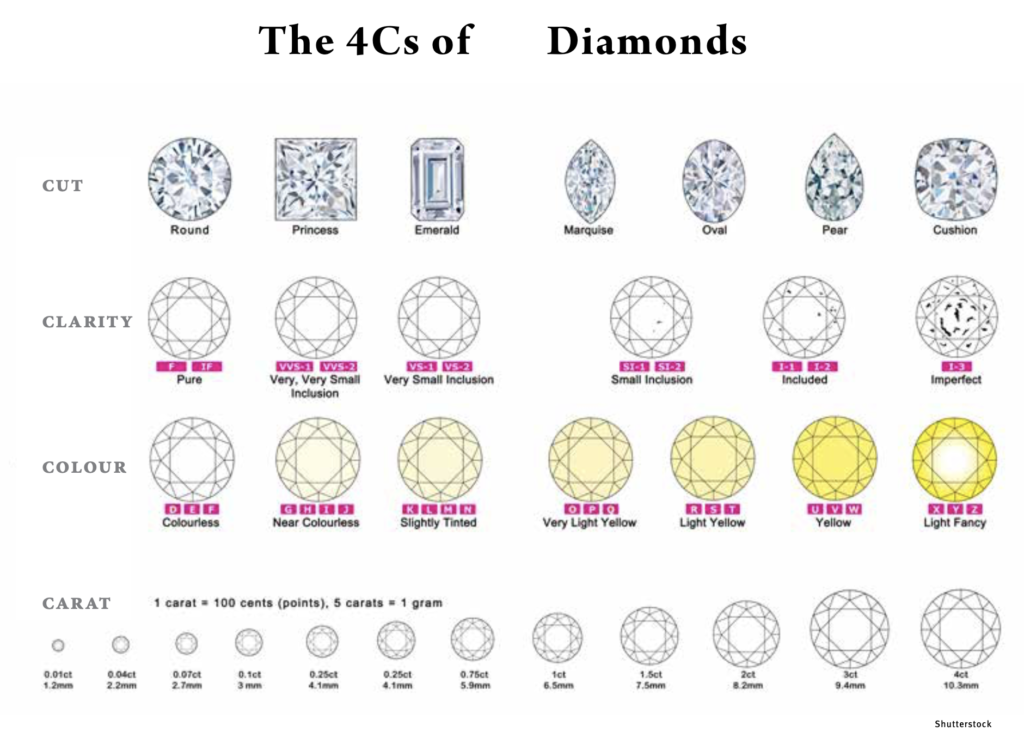

The 4Cs – cut, clarity, colour, and carat – are the globally accepted standards for assessing the quality of a diamond. Cut is determined by how a diamond’s facets interact with light, clarity is a measure of the purity and rarity of the stone, colour refers to the natural tint inherent in white diamonds, and carat denotes the weight of a diamond.

CUT

Two diamonds may have the same clarity, colour and carat weight, but cut is what determines whether or not one is superior to the other. A diamond’s cut is determined by three factors: (i) precision of cut, how the size and angles relate to the different parts of the stone; (ii) symmetry, how precisely the various facets of a diamond align and intersect; and (iii) polish, the details and placement of the facet shapes as well as the outside finish of the diamond.

Three diamond cuts are used to craft every diamond shape: brilliant cut, step cut, and mixed cut. The choice of diamond cut is usually decided by the shape of the rough stone, the location of imperfections (inclusions) found within the structure of the diamond, and the preservation of carat weight. The cutter must take each of these factors into consideration.

The most popular facet arrangement is the brilliant cut, which is made up of triangular and kite- shaped facets. The modern round brilliant, which has 58 facets, is the most dazzling of diamond cuts. The brilliant faceting style is also used to cut cushion, oval, marquise, pear and heart-shaped diamonds.

In contrast to brilliant diamonds, step-cut diamonds have trapezoidal facets that run parallel to the middle, or girdle, of the diamond. These stones typically have their corners truncated, as sharp corners are points of weakness where the diamond may cleave or fracture. The result is the emerald-cut diamond, which classically has a length-to-width ratio of around 1.5. A related cut is a square modified emerald cut called the Asscher cut. Mixed cuts have a combination of brilliant and step-cut facets.

CLARITY

Diamond clarity is a measure of the purity and rarity of the stone, graded by the visibility of these characteristics under 10-power magnification. As per the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) grading system, a stone is graded as flawless (FL) if no inclusions (internal flaws) and no blemishes (external imperfections) are visible. The IF grade is given to a diamond that is internally flawless.

Diamonds with the most minimal inclusions are designated VVS-1 and VVS-2 (meaning “very, very slightly” included) and VS-1 and VS-2 (meaning “very slightly” included). Diamonds with more noticeable imperfections are denoted SI-1 and SI-2, denoting “slightly included”, while the poorest grades are reserved for diamonds deemed “included” (I-1) or “imperfect” (I-2 and I-3).

Inclusions are materials – solids, liquids or gases – that were trapped in the diamond as it formed. These produce structural imperfections that may make a diamond appear whitish or cloudy. The relative clarity of a diamond can be affected by the number, size, colour, location, orientation, and visibility of inclusions. In addition to such internal characteristics, surface defects, called blemishes, can also influence clarity. These include grain boundaries, scratches, chips, and spots.

Interestingly, only around one in five diamonds has a clarity rating high enough for it to be considered appropriate for use as a gemstone. The remaining 80 percent are relegated to industrial use, such as in cutting and grinding tools. As you’d expect, diamonds become increasingly rare – and therefore more valuable – as clarity increases. VVS, VS and SI diamonds are among the most expensive, while the diamonds that command the highest premiums are FL and IF stones, which are so rare that they are sometimes referred to as “museum quality” diamonds.

COLOUR

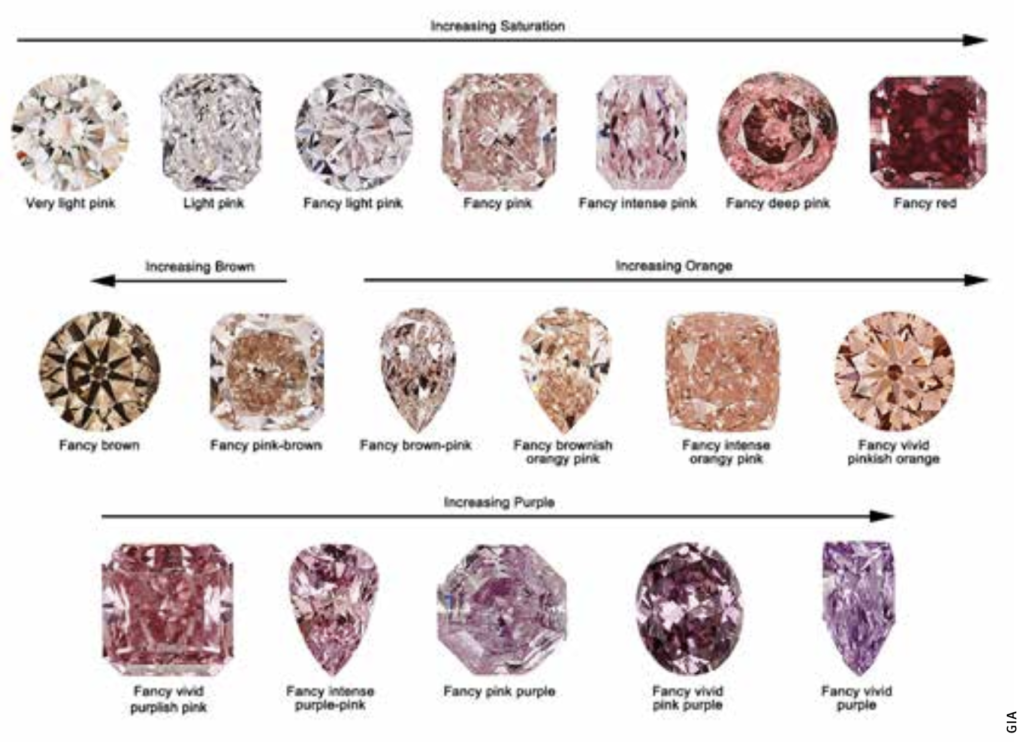

Most mined diamonds fall within the so-called “normal colour” range. Such diamonds are graded from D (totally colourless) to Z (pale yellow or brown). Diamond graders compare a specimen of unknown grade against a master set of diamonds, assessing where in the range of colour the sample resides. Diamonds of more intense colour – usually yellow, but also red, pink, green, blue and black – are termed “fancy colour” diamonds.

Diamonds are classified into two main types and various subtypes, according to the nature of their chemical impurities. It is these impurities, measured at the atomic level using an infrared spectrometer, that determine a diamond’s colour. Type Ia diamonds, which make up 95 percent of all natural diamonds, contain nitrogen as their main impurity. The absorption spectrum of the nitrogen clusters causes the diamond to absorb blue light, making it appear pale yellow or almost colourless.

Type IIa diamonds, by contrast, have no measurable nitrogen impurities. Such stones, which make up one to two percent of all natural diamonds, were formed under very high pressure for longer time periods. These diamonds can be subjected to extreme pressure and tension during the growth of their crystal structures, and this “plastic deformation” is believed to lead to imperfections that confer various colours to the diamond: yellow, brown, orange, pink, red, and purple. Rarer still are the Type IIb diamonds, which contain significant boron impurities, lending these stones a light blue or grey colour. Some blue-grey diamonds are Type Ia, not Type IIb, and have large concentrations of defects and impurities; the origin of their colour is not well understood.

CARAT

The unit of measurement for the physical weight of diamonds is the carat. One carat equals 200 milligrams or 1/5 grams and is subdivided into 100 points or cents. Carat weight is measured using a highly accurate, calibrated digital scale. Large diamonds are rarer than small ones, and as the carat weight increases, the value of the diamond increases with it. However, the increase in value is not proportionate to the increase in size. For example, assuming colour, clarity and cut grade are the same, a 1-carat diamond will cost more than twice that of a 1⁄2-carat diamond.

*AG

For more stories from this upcoming Asian Geographic Pink Edition No.160, please subscribe at https://shop.asiangeo.com