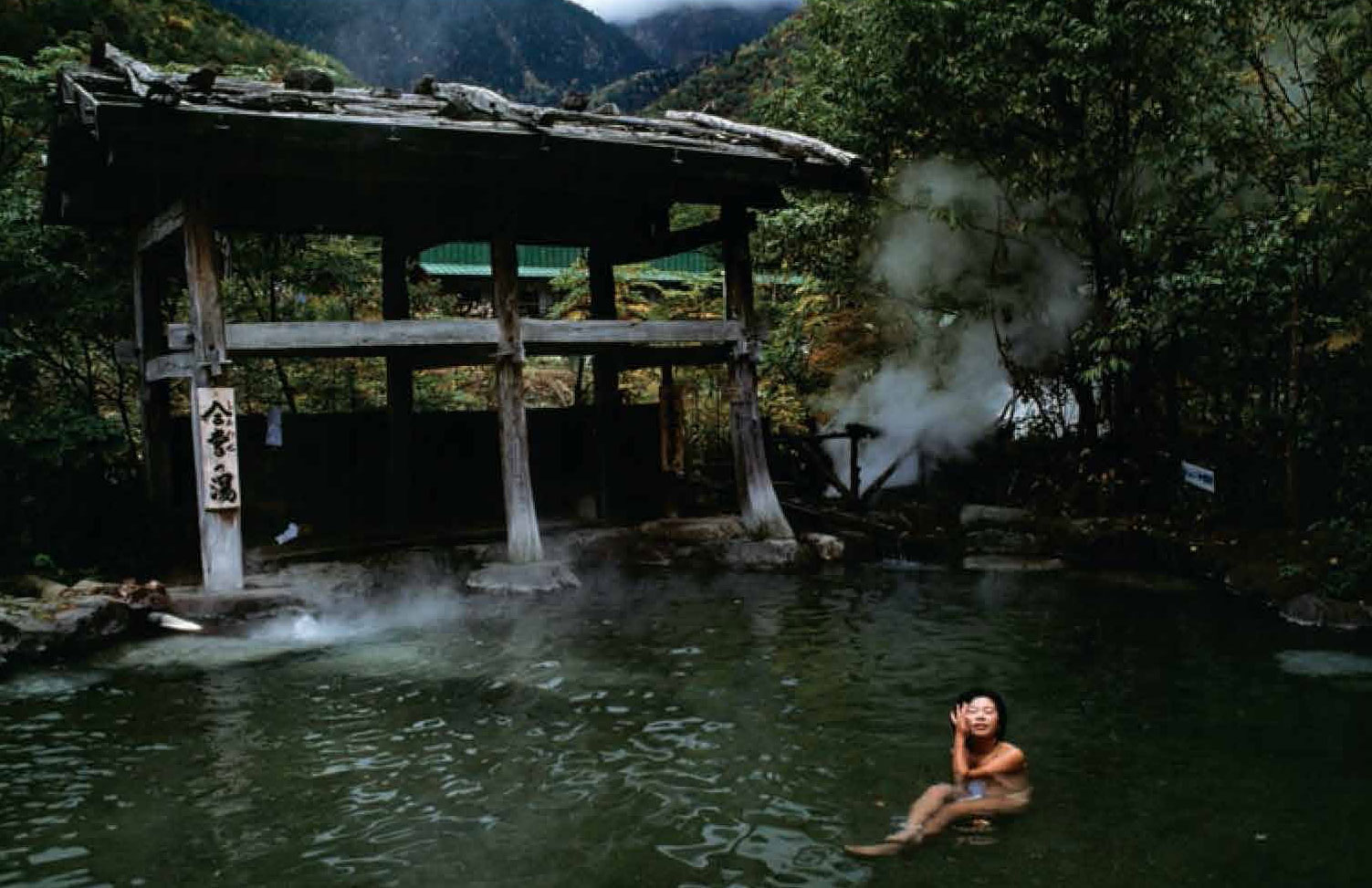

There’s a story in the Nihon-shoki, the 1,300-year-old annal of Japanese history and legend, that at DÕgo, in what is now the city of Matsuyama on the island of Shikoku, a white heron was spotted dipping its injured leg into hot water gushing out of the rocks.

The bird was healed in the process, encouraging the local aristocracy and priesthood to take to bathing

in naturally heated spring water. Soon everyone was following suit and a thousand years later, Japan’s craze for bathing in what are known as onsen is still going strong.

Straddling a major fault line in the earth’s crust, Japan is particularly blessed with onsen. Natural al fresco baths (called rotemburo or notemburo) occur pretty much anywhere from mountainsides and rivers to rocky holes along the seashore. However, the vast majority of onsen are housed indoors either in public bathhouse complexes or attached to ryokan-style accommodation – visiting such places to enjoy the baths, fine cuisine, general pampering and enforced idleness is the most popular way for Japanese to unwind.

For a spring to qualify as an onsen, it has to contain specified amounts of minerals, which vary by area. Different elements in the water are believed to soothe the body and heal various ailments. For example, an onsen containing sulphur may smell like rotten eggs but is said to be good for the arteries. Springs with a high salt or iron content will help calm inflamed joints and are best for skin problems. Carbonation in the water is believed to improve blood circulation and neurological complaints, while acidic springs are the choice of those who suffer diabetes.

Legally, onsen also must be able to produce naturally heated water above 25degC. For true enthusiasts however, the hotter the water, the better – the ultimate aim being to braise yourself until you turn into a yudedako (boiled octopus).

Check out the rest of this article in Asian Geographic No.73 Issue 4/2010 here or download a digital copy here