By Elyssa Yong

By far one of the most notorious families in the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda Marcos, made their mark on the country, but not in a way one would expect. Elected to the Philippines House of Representatives in 1949, Ferdinand quickly moved up the ranks and by 1965, he was inaugurated to his first term as President of the Philippines. This marked his 20 years regime that became increasingly authoritarian and corrupt.

ᐞ Ferdinand Marcos, 1982

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr., known simply as Ferdinand Marcos, was a Filipino politician, lawyer, and kleptocrat who served as the 10th President of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. As president, he adopted “Constitutional Authoritarianism” under the New Society Movement, which essentially allowed him to rule as a dictator under martial law from 1972 until 1981, and keep most of his legal authority until he was forced to step down in 1986.

In the first term of Ferdinand Marcos’ presidency, the Philippines became the second-largest economy in Asia, and Marcos pursued an aggressive program focused on infrastructure development funded by foreign investors and loans. This made him popular amongst the people, securing him a second term as president. Amongst the major projects that he embarked on in his first term, one of the most notable ones was the construction of the Cultural Center of the Philippines complex. His entire first term as president was deemed a success marked by the industrialisation, infrastructure development, and an increase in rice production for the country.

Moreover, after his election, Marcos began developing close relations with the officers in the military and expanded the armed forces by allowing loyal generals to stay in their positions until past their retirement age or giving them civilian government posts.

Later in 1969, Marcos campaigned for a second term, beginning with his nomination as the presidential candidate of the Nacionalista Party at its July 1969 general meeting. To garner the favour of the electorates, Marcos invested US$50 million into infrastructure projects. However, this backfired on him as the rapid and massive expenditure would ultimately be responsible for the Balance of Payments (BoP) crisis in 1970. The subsequent inflationary effect caused widespread social unrest and dissent.

ᐞ President and Mrs. Lyndon Johnson and President and Mrs. Ferdinand Marcos at the White House, 1966

The Marcos administration had to go to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help. The IMF offered a debt restructuring deal, which resulted in the implementation of new policies, including greater emphasis on exports and a relaxation of controls over the peso. The conditions from IMF included a reduction in selected tariff rates as well as a 43 percent monetary devaluation on the peso. In fact, due to the BoP crisis, the exchange rate plummeted from 3.9 pesos to a US dollar in 1969, to 6 pesos to a US dollar in 1970. This led to rapid inflation.

In 1969, Marcos was re-elected for his second term, but this time, his term was characterised by social discontent stemming from the 1969 Balance of Payments Crisis. At this point, opposition groups have begun to form, with the media classifying the various civil society groups into two categories: the “moderates” and the “radicals”.

The “moderates” included church groups, civil libertarians, and nationalist politicians who were demanding change through political reforms. The “radicals”, on the other hand, included several labour and student groups who wanted broader, more extreme systemic political reforms. A slew of protests and demonstrations against Marcos and his administration began rocking the nation.

In 1972, following a series of bombings in Manila, Marcos was warned of an imminent communist takeover and enacted the martial law in response. With the issue of Proclamation 1081, Marcos had effectively overwritten the constitution. His term was supposed to end in December 1973 in accordance with the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines, which states that he was only allowed to be the president for two four-year terms. The martial law allowed him to extend his term indefinitely, marking the beginning of his authoritarian rule.

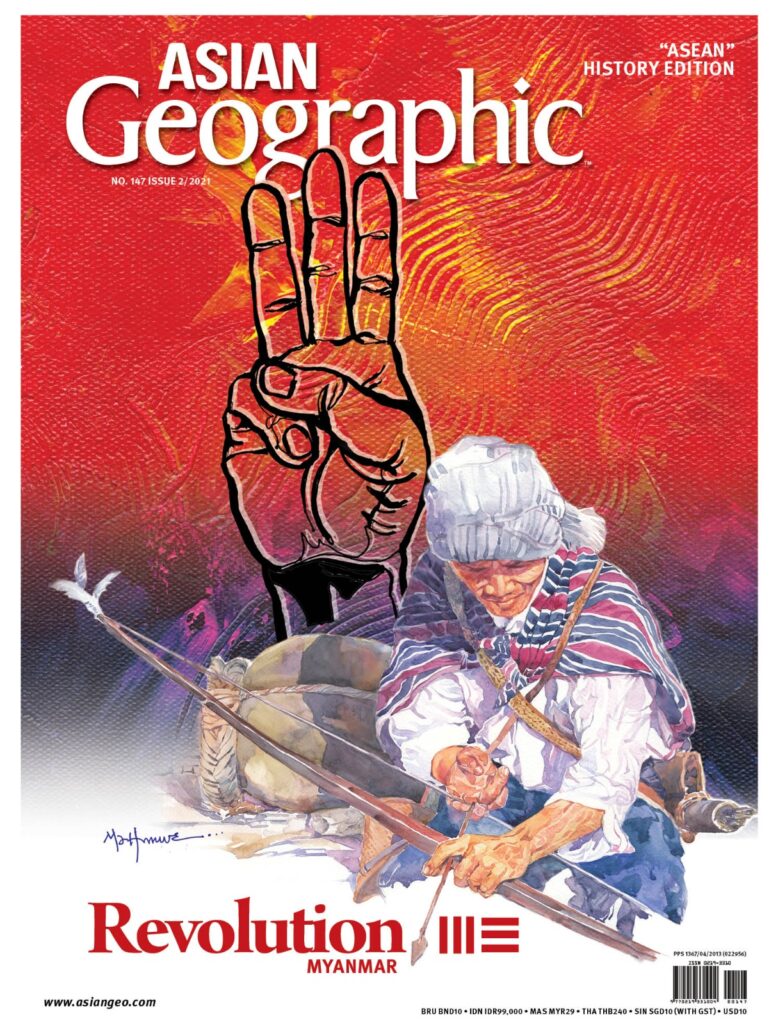

Read more about the History of the Philippines and their departure from authoritarianism, check out Asian Geographic Magazine Issue 2/2021 coming to the shelves soon or reserve your copy by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com.

Read more about the History of the Philippines and their departure from authoritarianism, check out Asian Geographic Magazine Issue 2/2021 coming to the shelves soon or reserve your copy by emailing marketing@asiangeo.com.

Subscribe to Asian Geographic Magazine here or for more details, please visit https://www.shop.asiangeo.com/