(text & photos: SOPHIE IBBOTSON & MAX LOVELL-HOARE)

WHEN IT COMES TO WINEMAKING, the French are the new kids on the block and New World wines are scarcely more than a glint in the milkman’s eye. We know that the Greeks and Romans, both the mortals and their gods, enjoyed an amphora of wine or two; indeed, the Greek’s earliest name for southern Italy was Oenotria (“the land of vines”). This is far from the start of the story, however, as a little to the east, in a southern corner of the Caucasus, the Georgians had been confidently making fine wines since at least the seventh millennium BC.

Some 8,000 years after the first Georgian successfully fermented his grapes, drank the proceeds and felt sufficiently generous to enlighten his neighbours about his discovery, we arrived in Tbilisi, the country’s modern capital, on an Aerosvit flight from Kiev. The official cast a cursory glance at our passport photos, wielded his stamp with a flourish and then, la pièce de résistance: we were each presented with a bottle of Georgian wine. It wasn’t an attempt to bribe visiting journalists; it’s standard protocol. Every new arrival receives red wine. This simple gesture says that you’re warmly welcome in Georgia, and that even in the 21st century, wine remains at the very heart of Georgian hospitality and culture.

With so many vines and so little time, we needed an expert guide. Fortunately, they don’t come much more expert than Eko Glonti of Lagvinari, a Georgian wine lover and fine wine producer, who has made it his mission to revive the traditional art of Georgian winemaking and to share it with the world. Our palates were in for a treat.

A fine wine starts with the raw materials:the grapes. There are nearly 400 grape varieties indigenous to Georgia, though less than a tenth of these are still commercially grown. Of these, the Rkatsiteli (white) and Saperavi (red) are the two most popular. Traditionally, each different variety of vines was paired with a specific terroir (the natural environment, including soil, topography and climate, in which vines are grown) to produce the highest quality of grape and also unique regional wines.

Meticulous records of these pairings, and indeed of all aspects of viticulture, were made and preserved in Georgia’s Orthodox monasteries, as the tending of vines and production of both sacramental wine and wines for everyday drinking was an integral part of the monks’ work. Some of the most detailed historical wine records were kept at the sixth-century Ikalto Monastery near Telavi in Kakheti (Georgia’s dominant wine-producing region) and as you wander around the recently restored complex, the churches and other ecclesiastical buildings still lie side by side with grape presses and wine cellars, and lines of discarded kvevris (vast clay jars in which wines are traditionally fermented and stored) are propped up along dry stone walls.

Only now, 20 years after independence, are Eko and his fellow Georgian winemakers able to rediscover this wealth of ancient knowledge; what was collected and so carefully preserved for millennia was almost lost forever during the Soviet era when monasteries were destroyed, their monks killed or exiled, and mass production without regard for quality became the focus of agricultural policy.

Georgia’s finest vines have always been grown on the mountain slopes as opposed to flat valley bottoms. Though yields on these slopes are often lower, mineral-rich springs and streams feed the vines, and the drainage of the soil is also better. The Caucasian Mountains have a moderate climate, with warm, moist air drifting across from the Black Sea. The winter months are relatively mild, with little, if any frost at the lower altitudes, and the long, warm summers give the grapes plenty of time to ripen and become naturally very sweet.

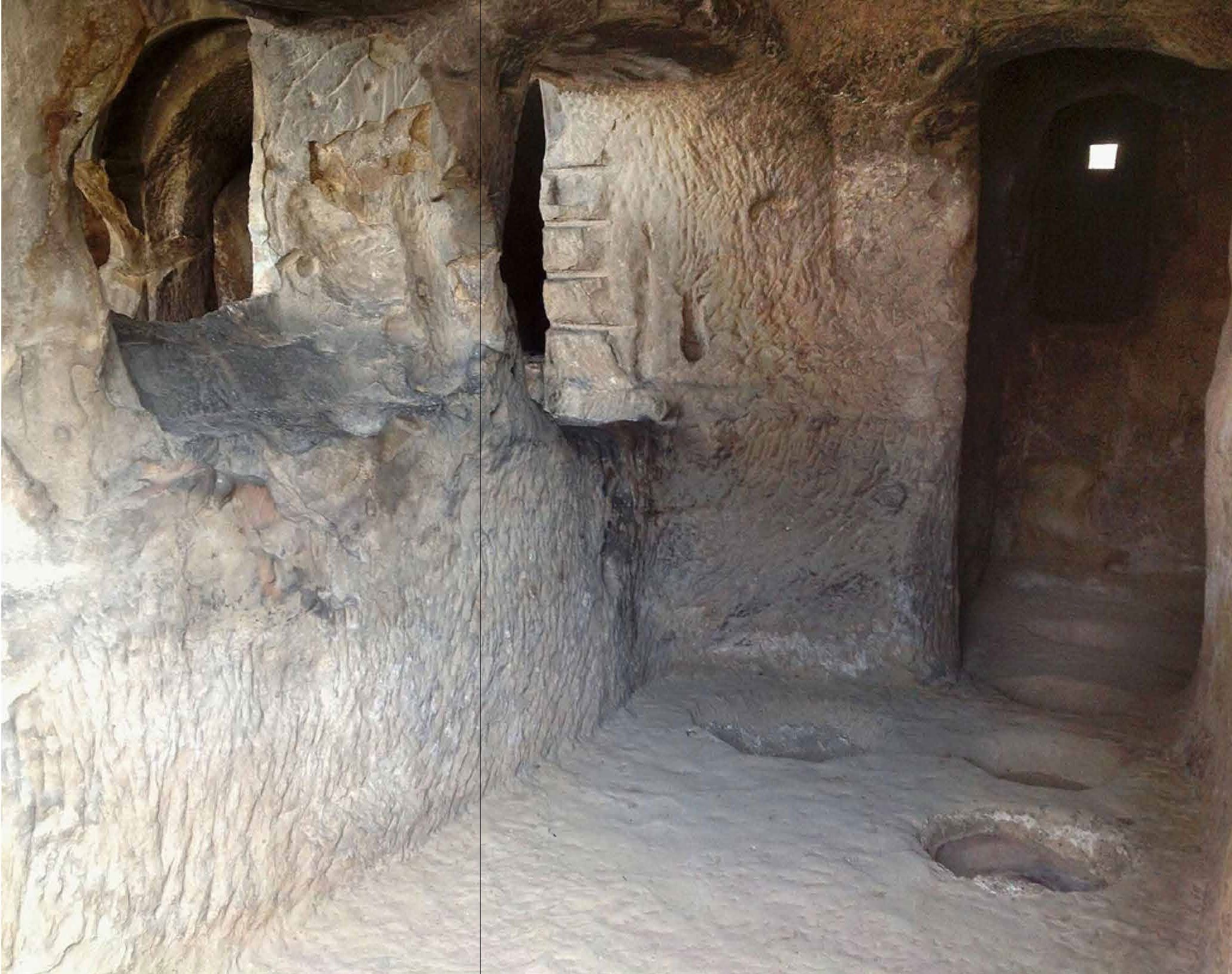

Grapes are still harvested by hand, then pressed to release their juice in one of two ways. Deep stone troughs in the Uplistsikhe Archaeological Museum, a rock-cut monastery complex first carved out in the 10th century BC, show that the crushing of grapes was historically done underfoot, the juice running out through narrow channels into a second trough below. Each trough is more than three metres long, which indicates the scale of this ancient production.

More familiar to today’s artisanal winemakers, however, are the wooden presses still often found in the cellars of older houses. Some two to three metres wide, the grapes are tipped into the top, and a giant brass screw can be turned to ensure maximum juice is extracted. The skins are not to be wasted, though, for Georgian winemaking requires that the skins (called the must) should be fermented along with the grape juice, giving the resulting wine its unique colour and flavour.

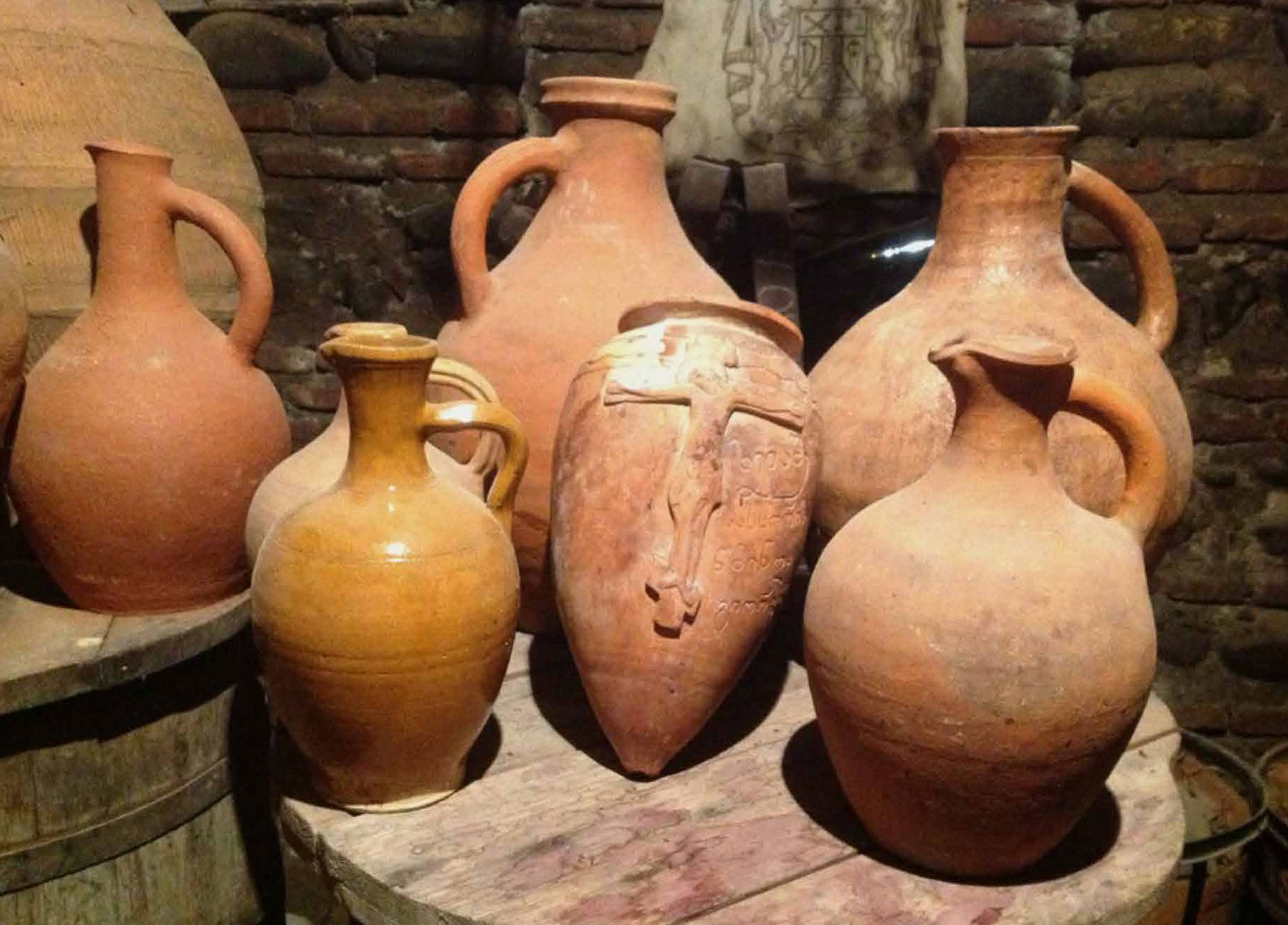

Wine is fermented, and later stored, in a kvevri, a vast clay pot – 8,000–10,000-litre capacity is not uncommon – coated outside with lime and sealed inside with natural beeswax. The kvevri is buried beneath the ground, and it is this step that enabled Georgia’s ancient winemakers to achieve such early successes, as it ensures the wine is kept at a constant temperature throughout the fermentation process. As the kvevri is pointed at the bottom, grape seeds sink to the bottom whilst the skins float to the top; no additives are required to separate the sediment from the wine.

Though kvevri making was once widespread in Georgia, it is sadly a dying art. There are now kvevri makers in only three of Georgia’s regions: Kakheti, Imereti and Guria. With the majority of winemakers using modern metal vats, purists have a second fight on their hands – saving kvevri production – if they are to be able to continue making Georgian wines in the traditional way.

Read the rest of this article in No.96 Issue 3/2013 of Asian Geographic magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.