(Text and Photos by SOPHIE IBBOTSON AND MAX LOVELL-HOARE)

WHAT do you give the man who has everything? How about the heavens? Not content with their earthly domains, kings have often looked to the stars for confirmation of their divine right to rule, and indications of what the future might bring. Their patronage and personal interest in astronomy has driven forward our understanding not only of our own Solar System but also of the planets beyond.

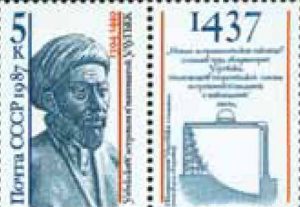

Astronomy had been a royal pursuit for thousands of years. The ancient Egyptians aligned their pyramids to the stars and were able to accurately predict the flooding of the Nile by observing the star Sirius and the summer solstice. The Babylonians were producing star catalogues as long ago as 1200 BC. But it was the medieval emperor Ulugh Beg (1394–1449 AD) who took astronomy into the modern age, building a vast observatory and producing the most detailed star catalogue before that of respected Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe.

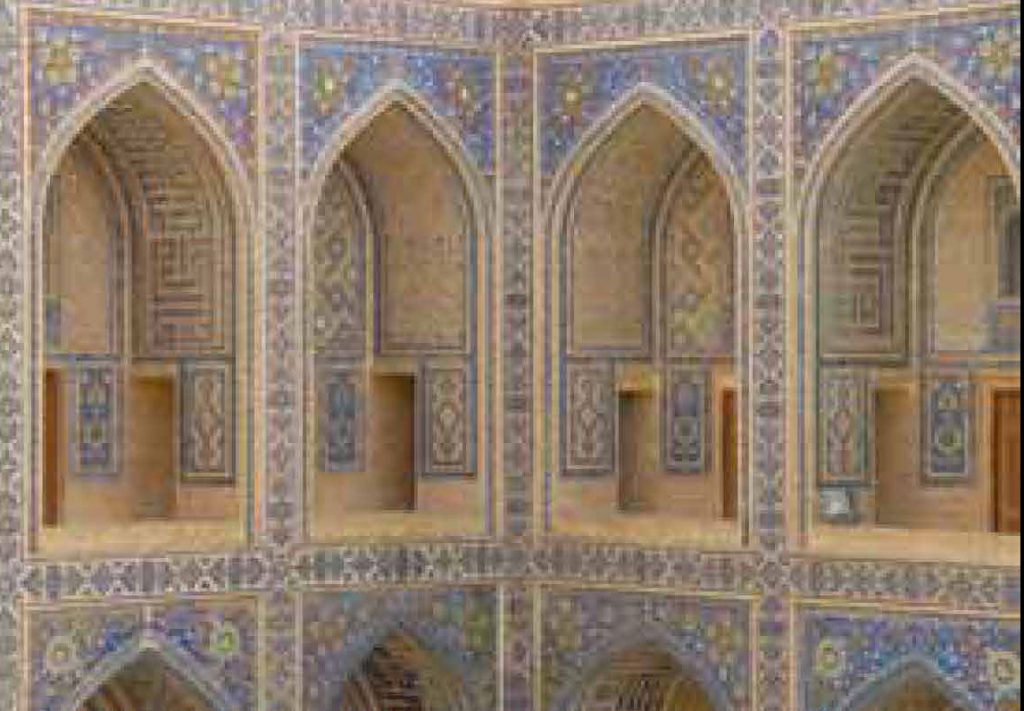

Ulugh Beg was born in Samarkand, present-day Uzbekistan, in 1394, and was the grandson of legendary conqueror Tamerlane. He lacked the political skills of his predecessors but instead focused on turning his capital into an intellectual centre for scholars from across the Islamic world. Having travelled to both India and the Middle East as a child, he was well aware of scientific developments in both those regions and was determined to build

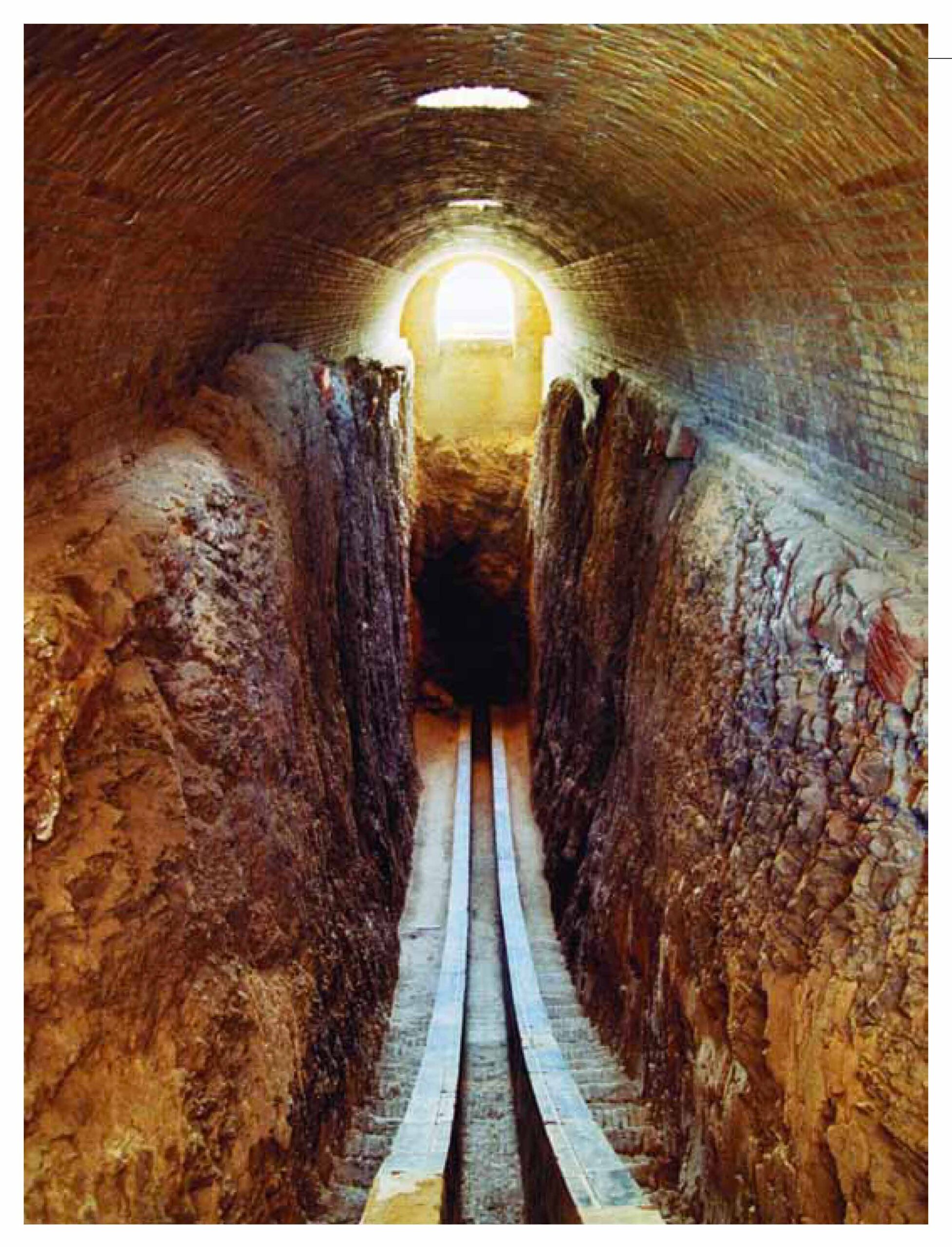

Given that Ulugh Beg and his astronomers were working without optics, the accuracy of their calculations is startling. Even today we do not have a more accurate calculation of the Earth’s axial tilt than Ulugh Beg’s 23.52 degrees, and his assertion that the year is 365 days, 6 hours, 10 minutes and 8 seconds in length is only one minute longer than modern electronic calculations. Had Ulugh Beg had more time to study the stars, he may have made more impressive measurements still, but fate was to intervene: in 1449, the observatory was destroyed by religious fanatics and would lie forgotten underground until it was rediscovered by an archaeologist in 1908. Ulugh Beg himself hardly met a more glamorous fate: he was beheaded by his own son en route to Mecca and his remains were interred in Tamerlane’s tomb.

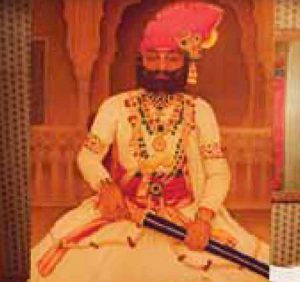

Two hundred and fifty years later, and a thousand miles away, another boy king would look to the stars and wonder what fortunes the heavens held for him. When Maharaja Jai Singh II succeeded his father to the throne of Amber in 1699, he was barely able to support 1,000 cavalry, and the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb was flexing his muscles across India. It would be over 30 years before Jai Singh could secure his territories and engage in his twin passions of architecture and astronomy.

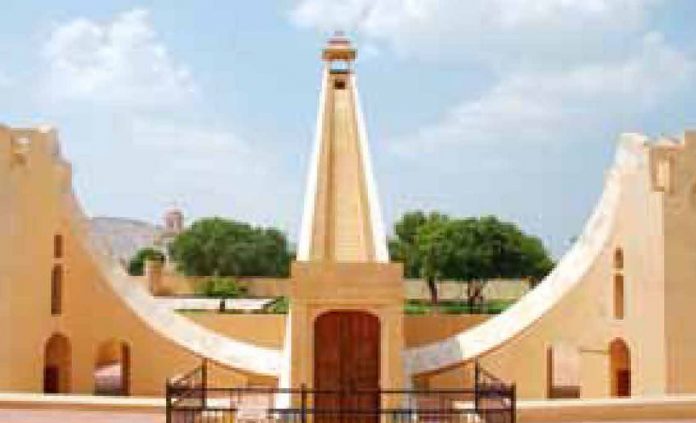

Jai Singh constructed five observatories, four of which remain. Each observatory consisted of a central Ram Yantra (a cylindrical building with an open top and a pillar in its centre), a concave hemisphere called the Jai Prakash, the Samrat Yantra (an equinoctial dial), the Digamsha Yantra (a pillar surrounded by two circular walls) and the Narivalaya Yantra (a cylindrical dial). The finest of these observatories, known as the Jantar Mantar (meaning “instrument” and “formula” or “calculation”), is next to the palace in Jaipur, the city Jai Singh planned and began building in Rajasthan in 1727. The new city quickly replaced his capital at Amber, and the instruments were used to predict eclipses and other astronomical events that were important in the Hindu calendar.

In the design of his observatories, Jai Singh incorporated early Greek and Persian elements he had read about. However, his designs were far larger and more complex, and calculations were made to a correspondingly greater accuracy. Perhaps of greatest interest are the 12 Rasivalayas, the zodiac-linked structures that enable astronomers to directly measure the latitude and longitude of a celestial object as it crosses the meridian line. The Samrat Yantra is, at over 22 metres, the largest sundial in the world, and the time can be accurately measured as the shadow that is cast passes over the quadrant scale beneath. Unlike a normal sundial, the Samrat Yantra could also be used to tell the time at night, as astronomers could calculate the position of prominent stars relative to the meridian.

Read the rest of this article in No.82 Issue 5/2011 of Asian Geographic magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.

![The Road to Independence: Malaya’s Battle Against Communism [1948-1960]](https://asiangeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/WhatsApp-Image-2021-07-26-at-11.07.56-AM-218x150.jpeg)