We know of opium as the addictive narcotic that once held Asia drugged and spellbound. But the people of Myanmar, Laos and Thailand – still major producers of this “joy fruit” – once had a healthy relationship with its intoxicating effects

Fields of poppy flowers did not initially cover the lush highlands straddling Laos, Myanmar and Thailand. And while this region, known today as the Golden Triangle, maintains its reputation as the centre of illicit opium production in Southeast Asia, its peoples’ tumultuous history with the plant begins in a manner far more harmonious than modern developments would have observers believe. Even before colonial powers created new plantations across Southeast Asia to capitalise on lucrative sales following the Sino-British opium wars, poppies – and by extension, opium – was known and used by locals. The inhabitants of the Golden Triangle first conceived poppy latexes as a herb to be grown and eaten, and had little interaction with its modern (and more sinister) derivatives like heroin and morphine.

Opium was consumed by Burmese elites before the British arrived in the 1820s, writes Ashley Wright in the 2014 book Opium and Empire in South-East Asia. Jonathan Saha’s 2017 paper, “Colonizing Elephants: Animal Agency, Undead Capital and Imperial Science in British Burma”, claims the drug’s trance-inducing properties were also employed to treat sick elephants in Burmese elephant camps, acting as tranquilisers during medical procedures for the behemoths. Hans Derks, in his 2012 book History of the Opium Problem, listed the first reference to opium use in Southeast Asia as 1366 (Thailand) and 1519 (Myanmar). Though opium first originated from Mesopotamia and was first traded on a large scale by the Dutch, “Arab and Portuguese traders, respectively, must have brought [opium] as a present to native rulers,” Derks writes, in his tracing of how the poppy flower found its way into Southeast Asia. It has also been posited that the hill tribes migrated into the Golden Triangle already armed with poppy seeds and knowledge of its cultivation techniques thanks to Chinese influence.

Related: Uncharted Territories

Despite the availability of poppies in the Golden Triangle before imperialisation, “nowhere in those [intervening] years did any form of large scale opium business in Asia exist, and there was no opium problem whatsoever,” Derks writes. Rather, the Hmong and Mien hill tribes in the area used the plant in rituals and folk remedies to treat simple maladies like stress, coughs, and toothaches. Whenever opium was smoked – for it was – among the Hmong community, it never reached a state of hopeless intoxication as was infamously the case in China. Instead, it was only socially acceptable for elders to pass the remainder of their lives in the peaceful, euphoric embrace of the drug’s effects. Young people in the community who got addicted faced disgrace and social exclusion.

Related: The Himalayan Parasite Worth More Than Gold

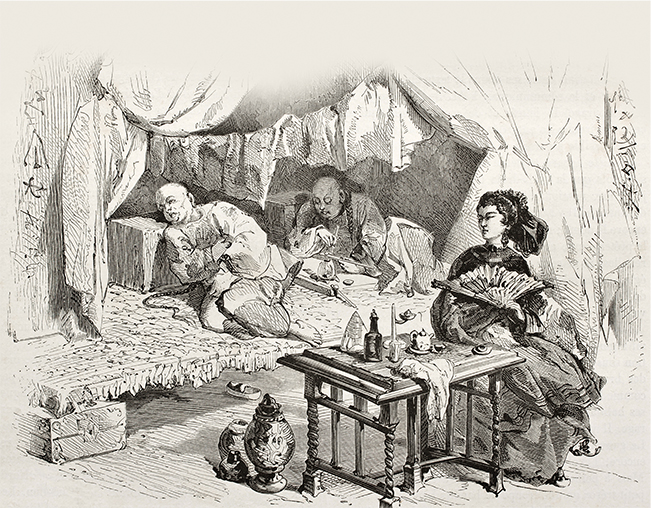

It was only after the widespread narcotic use of the drug did the evils of opium begin to reveal themselves across the region. Influenced by Chinese immigrants, opium farms and dens quickly began sprouting in countries like Singapore, Vietnam and Malaysia. Brothels began offering the drug, earning the pastime its permanent association with vice. In the meantime, British and French-led campaigns to encourage farmers in the Golden Triangle to grow ever more of the low-maintenance yet lucrative cash crop led to the beginning of their peoples’ addiction. Today, eradication programmes have vastly reduced the growing and use of opium – and its derivative, heroin – though it still remains a major problem in some areas. Addicts would do well to take a leaf out of the Hmongs’ book, and know their own limits…

Related: Ancient Remedies : East vs West

For other stories from this issue, see Asian Geographic Issue 131, 2018