By Karin Ronnow Photos Erik Petersen

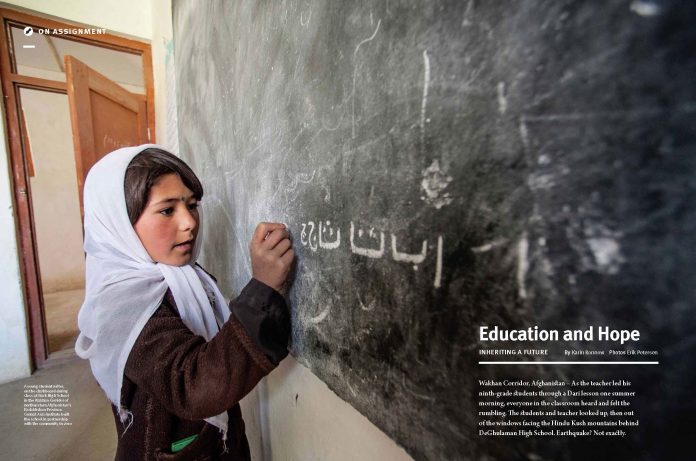

Wakhan Corridor, Afghanistan – As the teacher led his ninth-grade students through a Dari lesson one summer morning, everyone in the classroom heard and felt the rumbling. The students and teacher looked up, then out of the windows facing the Hindu Kush mountains behind DeGhulaman High School. Earthquake? Not exactly.

Within seconds, a herd of huge, burly yaks stampeded past the school, thundering toward the river. The yaks’ hoof beats shook the ground and momentarily drowned out the voices in the classroom. As the yaks thinned out, the students turned their attention back to the teacher and did not notice the young boy in threadbare clothes and Chinese rubber boots rounding up the stray yaks.

The boy should be in school. But like millions of children in Pakistan and Afghanistan, he has to work instead. When children reach school age in these impoverished societies, parents must weigh their two options: work or school.

“Everyone has a fierce desire for education, but where there is such abject poverty and survival depends on manual labour, many children are deprived of school,” says Greg Mortenson, co-founder of Central Asia Institute (CAI), a non-profit organisation that built DeGhulaman’s first school.

In DeGhulaman, most adults are illiterate and there are no paying jobs. Families herd sheep, goats and yaks, and grow small plots of grain and vegetables in the arid, high-altitude landscape.

The village children rise before sun-up, fetch water and collect dry yak dung and brush to fuel the fire. They milk the goats, sheep and camels, and later take the animals high into the mountains to graze. Everything is done by hand: ploughing, building, sewing. There are no shortcuts. In the face of such adversity, parents too often have no choice but to keep their children home from school to help support the family.

The UN Declaration of Human Rights unequivocally states that every child has a right to education. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, governments, community leaders and humanitarian groups like CAI are working with communities to make that right a reality. But the work is slow, labour-intensive and expensive.

“Grow Our Brain”

For centuries, education wasn’t even a dream in many places where CAI works. One generation of illiterate people succeeded another.

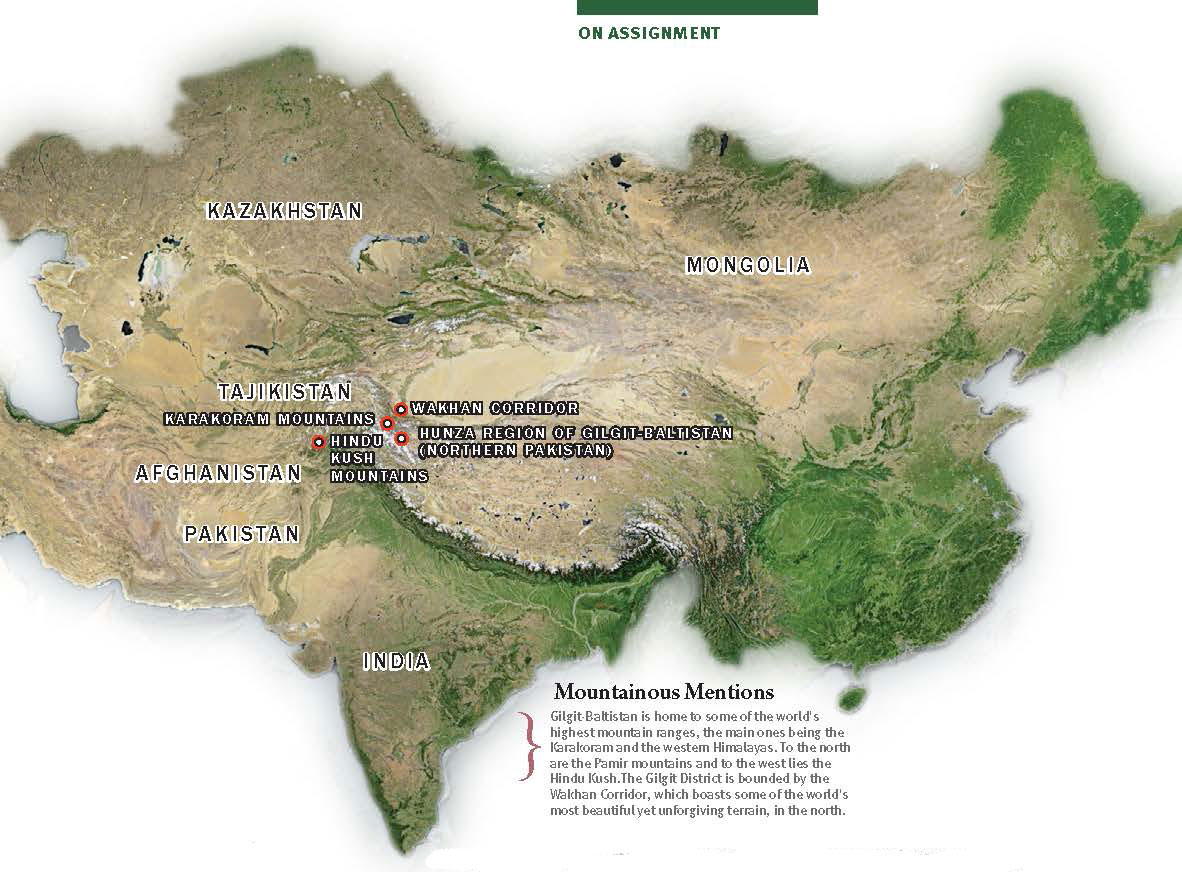

CAI began its work in the Karakoram mountains of northern Pakistan in the mid-1990s. According to Taha, village chief of Korphe, at the far end of Braldu Valley, in those days, thousands of climbers and trekkers came through the region, en route to K2 and the other famous nearby peaks. The area was renowned for its Marco Polo sheep, ibex and snow leopards. “But we had no school, books or pencils,” he says.

Communities had already begun to sense that something had to change. Populations were growing, putting pressure on limited resources, says Saidullah Baig, CAI’s programme manager in the Hunza region of Gilgit-Baltistan, in northern Pakistan. He cites the trend in remote areas for inherited land to be divided among so many family members and generations as to make parcels nearly worthless. “Eventually, they have no land there; it’s finished. That’s why we need men and women to work together for education and a better future.”

Wakhi poet and teacher Nazir Bulbul concurs. “The community believes the first priority is education. Because our land pieces are shrinking and there are no more job opportunities in those mountain areas, the only thing we could grow is our brain, so we want to do that.”

CAI’s work started in Pakistan’s northern areas and then expanded into Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Over the past two decades, CAI has helped establish or support nearly 300 schools, mostly in places that define the word “remote”. To get there requires traversing vertigo-inducing roads along mountain ridges and cliffs, through glacial streams, and over treacherous talus slopes. The destination is invariably well off the beaten path, where medical care is basic or non-existent, clean drinking water is rare, and sewer drainawge is primitive.

Although literacy rates are slowly increasing as students complete school, the adult literacy rates in many of these areas are still just climbing out of the single digits, especially among women.

“This work takes time,” admits Mortenson. “It takes patience and persistence, continuity and commitment.”

Check out the rest of this article in Asian Geographic No.111 Issue 3/2015 ) here or download a digital copy here