The Old City of Jerusalem is but one kilometre square. Within it is a microcosm of a whole world – the city markets still echo the great monumental scale of the Roman Cardo and Decumanus. What was once a 20-metre-wide grand arcade street – running north-south from city gate to city gate, along which were strung the great civic buildings, palaces, temples and gymnasia – gave structure to the city. Now, somewhat reduced in scale, the grand arcade is composed of three markets carved into the space of the singular Cardo, running parallel to each other – the butcher, the vegetable and the spice markets. Vaulted stone structures crowned by dramatic skylights provide shelter while allowing in daylight. Vendors push their merchandise out into a path four metres wide.

In the north-south direction, one is always walking at the same level from Damascus Gate (Bab al-Nasr in Arabic, Sha’ar Shkhem in Hebrew) to Zion Gate (Bab Harat al-Yahud in Arabic, Sha’ar Zion in Hebrew). In contrast, the east-west markets originate in Jaffa Gate (Bab el-Khalil in Arabic, Sha’ar Yafo in Hebrew), descend via steps, moving east towards the gateway of the Temple Mount.

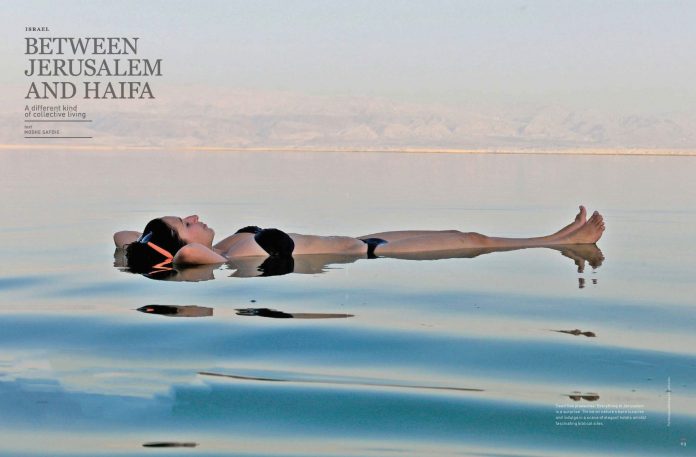

Not far from the crossroads of the markets, perched on an escarpment at the edge of the Jewish Quarter, is my house. It sits on a site where a Herodian Palace was once located, its ground level is Crusader, its mid-level Ottoman. The top floor is my own addition overlooking a 270-degree view of the Old City from the Holy Sepulchre to the northwest, the Western Wall and the Temple Mount, with the Rock of the Dome to the east, and the village of Silwan, the Dead Sea and the mountains of Moab in Jordan to the south.

Like many of the Old City buildings, two of my rooms consist of bridges across the pedestrian street below, and like many buildings of that era, they are stabilised by flying buttresses – arches supported by surrounding buildings. These structures are interdependent. It is more as if the Old City began as a solid mass out of which streets, terraces and houses were carved, forming one continuous, fractalised surface.

Below, you can walk in shade; above are terraces and dome structures. Today, unfortunately, these are covered by solar heaters, out-of-use TV antennas now replaced by satellite dishes and a multitude of other adaptations quite insensitive to the historic setting in which they are located.

To wander the alleys of the Old City is to be forever surprised. An innocent door in a wall opens up into a giant courtyard, beyond which is the imposing great dome of the Holy Sepulchre. Enter the Sepulchre and climb up one of the stairs towards the east and you emerge in a rooftop courtyard, surrounded by cypress trees and chambers inhabited by Ethiopian monks. Exit the courtyard towards the south and you are in one of the alleys of the Muslim Quarter.

Check out the rest of this article in Asian Geographic No.97 Issue 4/2013 here or download a digital copy here