Jia Sidao, the ambitious chancellor of the Song dynasty, creeps over to the daughter of the late emperor. He lulls the trusting little girl into a gripping story about binding one’s feet and then swiftly breaks her foot in a bid to subject her to the practice while her mother is away.

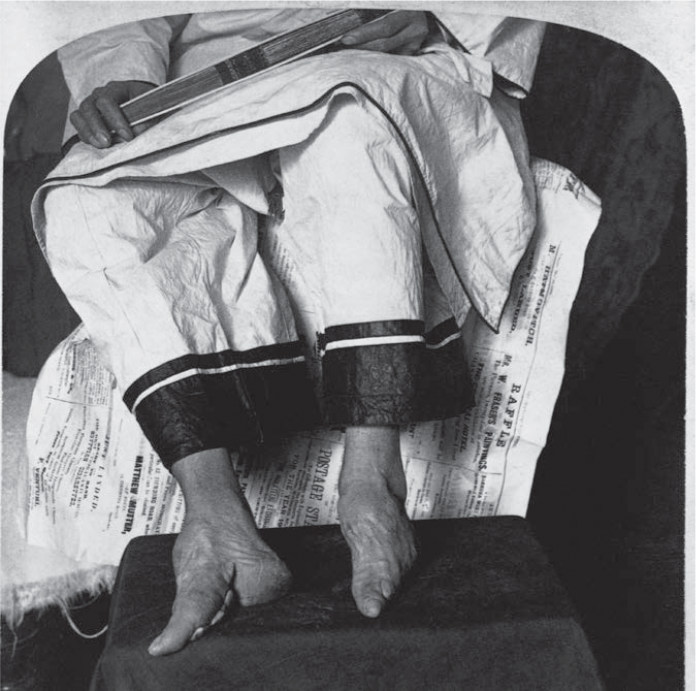

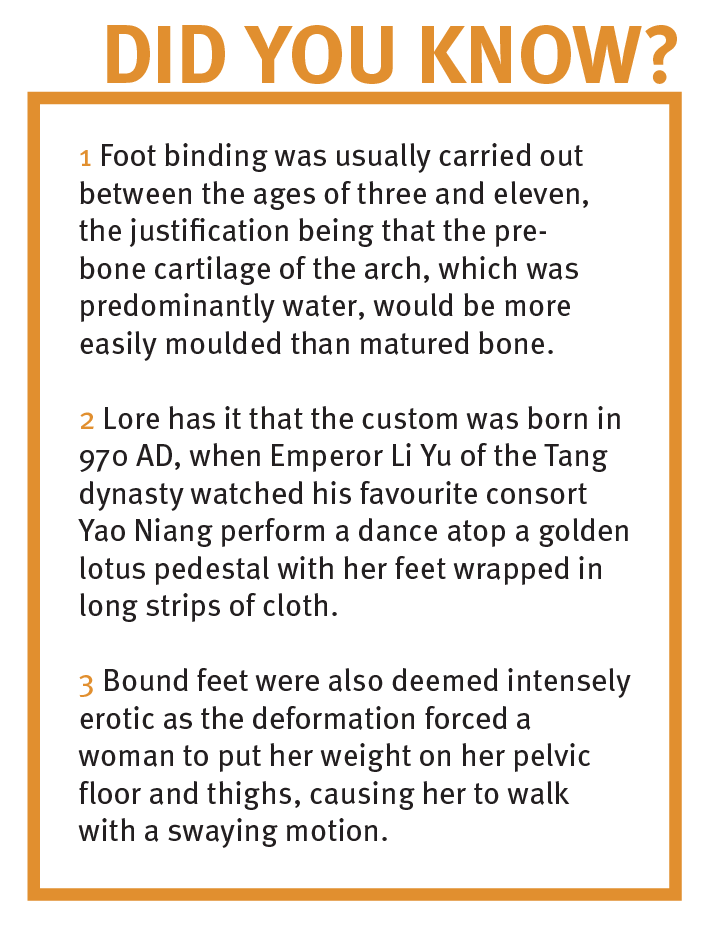

This is a heart-wrenching scene out of Marco Polo, a popular American television drama series set in the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). It depicts an ancient tradition known as chan zu, where girls had their feet forcefully manipulated to keep them narrower and shorter. The shoes were called san cun jin lian – three-inch golden lotus – because they “ideally” accommodated feet no longer than that measure, about eight centimetres.

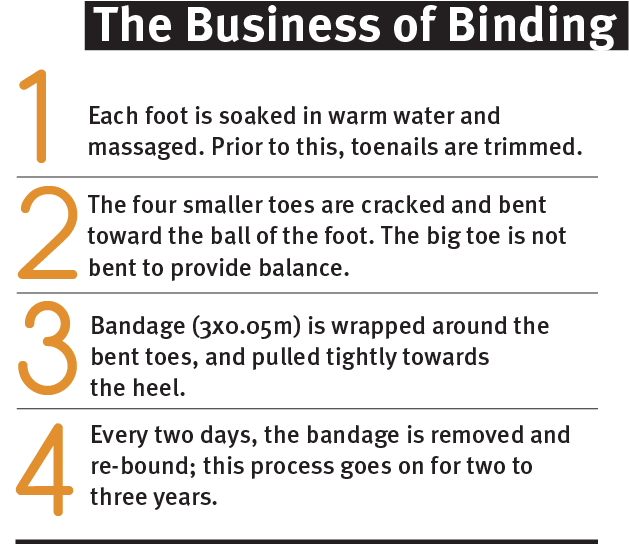

Lasting nearly 1,000 years, foot binding was initially neither considered mutilation nor punishment, but a form of embellishment to the human body. The thinking was that the smaller the woman’s feet, the more desirable she would be in marriage. Beginning around 970 AD, it later became a fashionable feature among court dancers of the Song dynasty. In 1271, when the Mongols founded the Yuan dynasty, they supported foot binding for all the females in China, mainly because it curtailed their physical freedom and made them more submissive.

This “prerequisite for marriage” belied the extreme cruelty being inflicted – foot binding resulted in crippling infections, blood poisoning and, in severe cases, even death. After a few failed attempts to abolish the practice during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661–1722), it was finally outlawed through the revolution of Sun Yat-sen in the early 20th century – leaving behind the remains of a vanished phenomenon marked for female repression.

Check out the rest of this article in Asian Geographic No.110 Issue 2/2015 by downloading a digital copy here. And subscribe here!