TWENTY TO 50 MILLION TONNES* of e-waste is generated annually worldwide. In Europe and the US, we throw away an old computer, on average, every two years. In the US, for every new machine bought, an old one is thrown away.

Each year, thousands of tonnes of old computers, mobile phones, batteries, cables, old cameras and other e-waste are dumped in landfill sites or burned. Thousands more are shipped, illegally, from Europe, the UK and the US to India and other developing countries for “recycling”. Some is sent as scrap, some as charity donations.

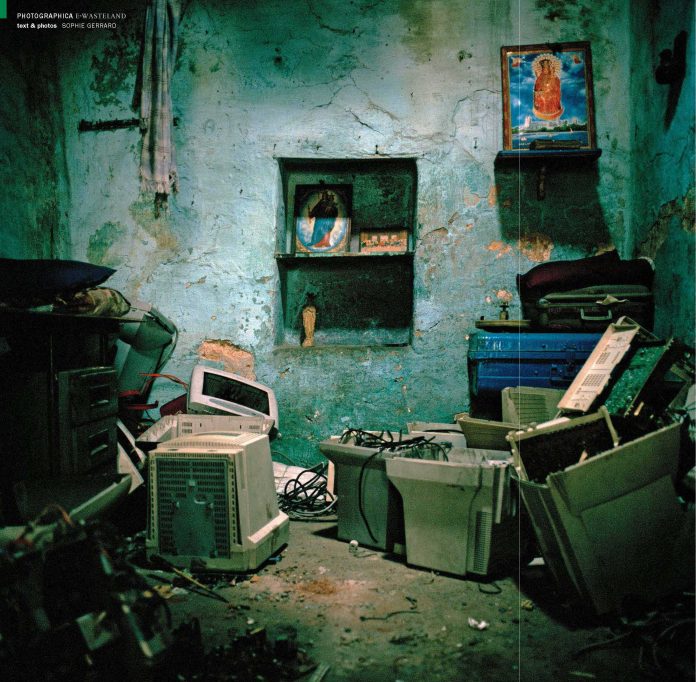

Shot in backyard recycling yards and scrap heaps on the outskirts of India’s major cities, E-wasteland explores the toxic truth behind the disposal of waste electronics from the West.

Documenting the problem of computer recycling in India through this set of images involved a lot of time spent trudging through back alleyways and toxic wastelands on the outskirts of India’s major cities. I met people whose everyday lives were completely polluted with the toxins and poisons from e-waste. Sitting among piles of debris, I met the men, women and children who dismantle and recycle the products we so heavily rely on.

These photographs explore the scale, repetitiveness and claustrophobic atmosphere of the unregulated and highly potent e-waste industry. Yet, it also documents the hidden and uncomfortable beauty in the mountains of poisonous computer parts. I didn’t want to present my audience with a view of India they’d seen before; instead, I photographed an almost hideous beauty in a way, something only made clearer when examined in detail.

For me, the tool of photography gives freedom to visually communicate stories and the lives of people and places I find interesting; that’s what it’s all about. So the aesthetics of an image is important. I want to attract my viewer and draw them in, make them give the image a second look – and then once their attention is captured, hope that they look even closer. It’s then that the context and captions become important. I researched the story of e-waste closely, using scientific articles, interviews and reports. The images I make are there to educate and inform.

India has become one of the world’s largest dumping grounds for e-waste. The problem is growing fast. E-waste is highly toxic. It contains lead, cadmium, mercury, tin, gold, copper, PVC and brominated, chlorinated and phosphorus-based flame retardants. Many of these heavy metals and contaminants are extremely harmful to humans, as well as to animals and plants.

When the e-waste arrives in India’s ports, it is dismantled by hand, incinerated and soaked in acid

by workers in backyard recycling scrap yards on the outskirts of many major cities. The workers have no form of health and safety assurance; they work in closed workshops without gloves, masks or eye protection and no regard for the environment. Once valuable materials like copper, gold and lead have been removed, the unwanted parts are then indiscriminately dumped into rivers and on wasteland or sent to landfill sites where lethal toxins contaminate the soil, groundwater and air.

E-wasteland presents the viewer with an aesthetic perspective of a deadly issue – a toxic landscape slowly poisoning its inhabitants and the environment.

Read the rest of this article in No. 97 Issue 4/2013 of Asian Geographic magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.