The natural wealth of the Philippines has spilt across the 7,107 islands of the archipelago. However, in a twist of fate, much of the diversity is now restricted to the areas of its natural origins – the slopes of the volcanic mountains. A recent expedition explored one such area in northern Negros, revealing an “old world” forest, concealing a rich natural, social and geologic history not tainted by the hand of progress, or even witnessed by “outside eyes”.

The Philippines rose from the collision of tectonic plates and volcanic activity. More than 50 million years ago, a series of “island arcs” rose far out in the Pacific Ocean. Following these, small but permanent islands protruded above sea level. Their shorelines rose and fell with the ice ages, some connected to one another by land bridges.

As time progressed and plate-tectonic movement continued, more islands of different shapes and sizes were established several hundred miles away from South-East Asia. As such, migration was virtually impossible for most creatures, and individual islands or island groups within the Philippines evolved in virtual isolation. The cocktail of volcanic creation and geographic isolation meant the islands became incubators of unique species.

No matter which group you consider – the birds, reptiles, amphibians – on average nearly 60 percent of all terrestrial vertebrate animals are unique to the Philippines. The diversity also differs between the islands groups, so much so that each could be considered a world unto itself. Such diversity is driven by abundant moisture, solar energy and the volcanic mountainous islands, which provide a spectrum of altitudes, creating a range of microclimates and thus growing conditions. Here, a huge variety of specialised plants and animals can find their own niche. The undulating islands were thus once cloaked in a range of forest types that covered 95 percent of the country.

However, the dual pressures of natural and anthropogenic influences means that much of the remaining forest (and inherent biodiversity) remains only in montane areas. The lowlands have been largely cleared; with forest now covering less than 15 percent. That which remains is closely associated with the volcanic mountains since it has limited development or agriculture potential but is still under threat from hunting and illegal logging, amongst other pressures. As such, these areas are coming under increasing conservation focus, yet many remain unexplored.

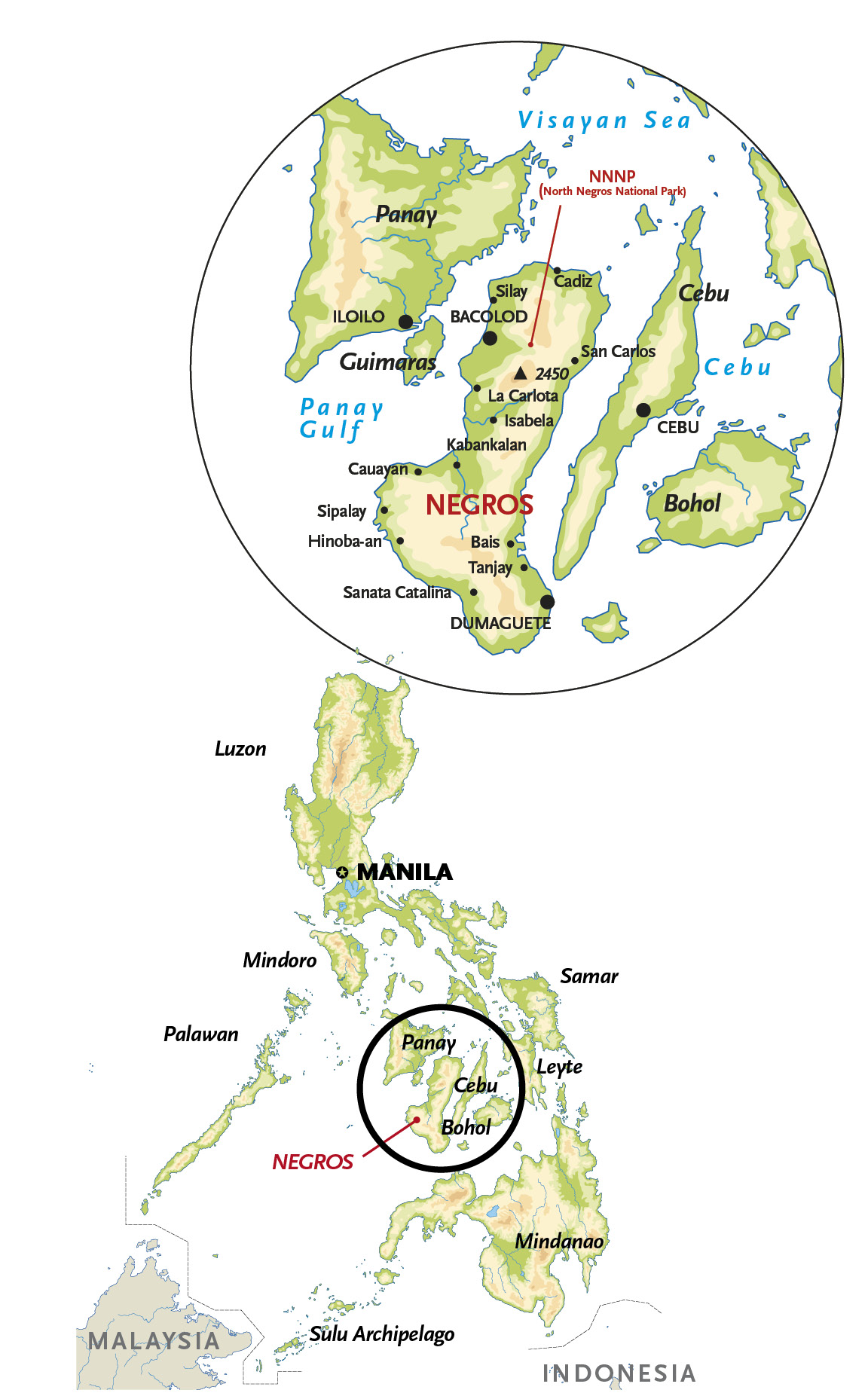

In April 2009, a small team undertook the Negros Interior Biodiversity Expedition (www. rainforestexpedition.org) to explore the “interior” forest of the North Negros Natural Park (NNNP), formerly the North Negros Forest Reserve. The park gravitates around the peaks of Mount Mandalagan and Mount Silay in the northern part of Negros Island in the central Philippines. The forests of the NNNP are surrounded by an encroaching wave of subsistence agriculture. Whilst researchers and conservationists had begun to explore the outer slopes of the park, none had ventured into the “interior” forest. They were perhaps held at bay by the terrain, which is typified by precipitous ridgelines and peaks, making movement on foot arduous and difficult. Landslides are common and mild tectonic activity still exists.

The interior is a raised plateau of primary forest, believed to be part of the old ash cone of an extinct volcano, which has been eroded by hydrological forces into its current form. The self sufficient expedition team traversed the park and documented on the outer edges the changing human impact, from the past history of Japanese occupation to unexploded WWII bombs, evidence of past rebel group activity and current signs of hunting and plant collection. Further in, the team also witnessed the natural power of the creation of the Philippines. Breaks in the forest revealed active sulphur vents roaring like jet engines and the lost worlds of volcanic craters; clear evidence of the origins of the island and still shrouded in much of its original forest cover.

For the rest of this article (Asian Geographic No.70 Issue 1/2010) and other stories, check out our past issues here or download a digital copy here