By YD Bar-Ness

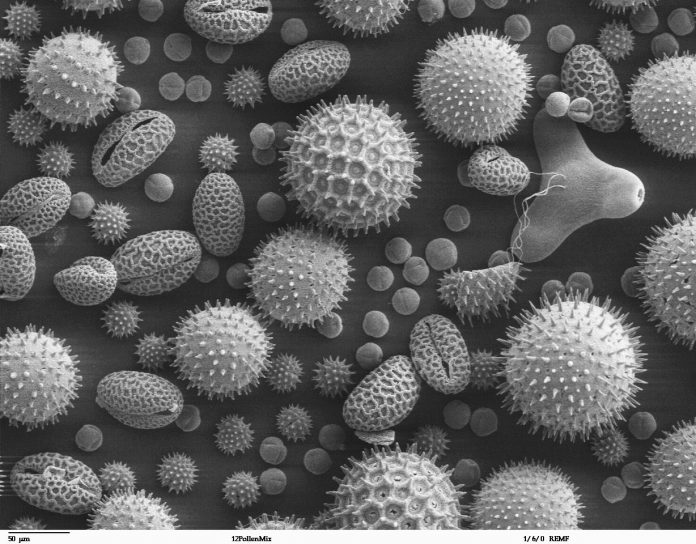

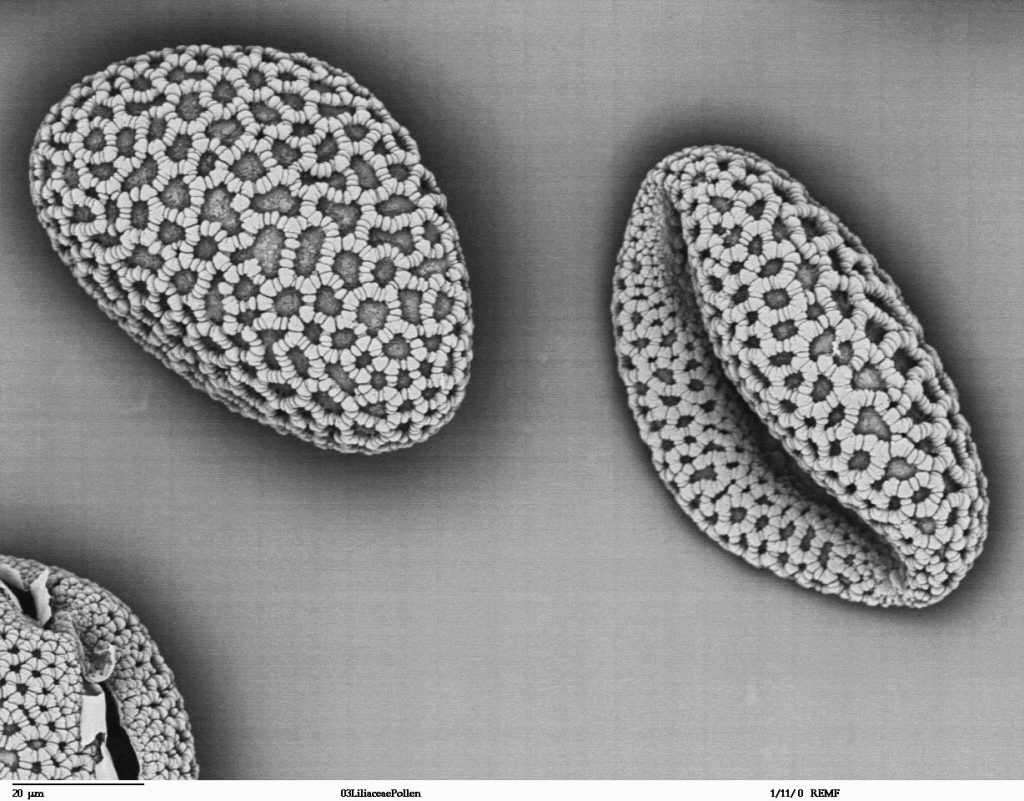

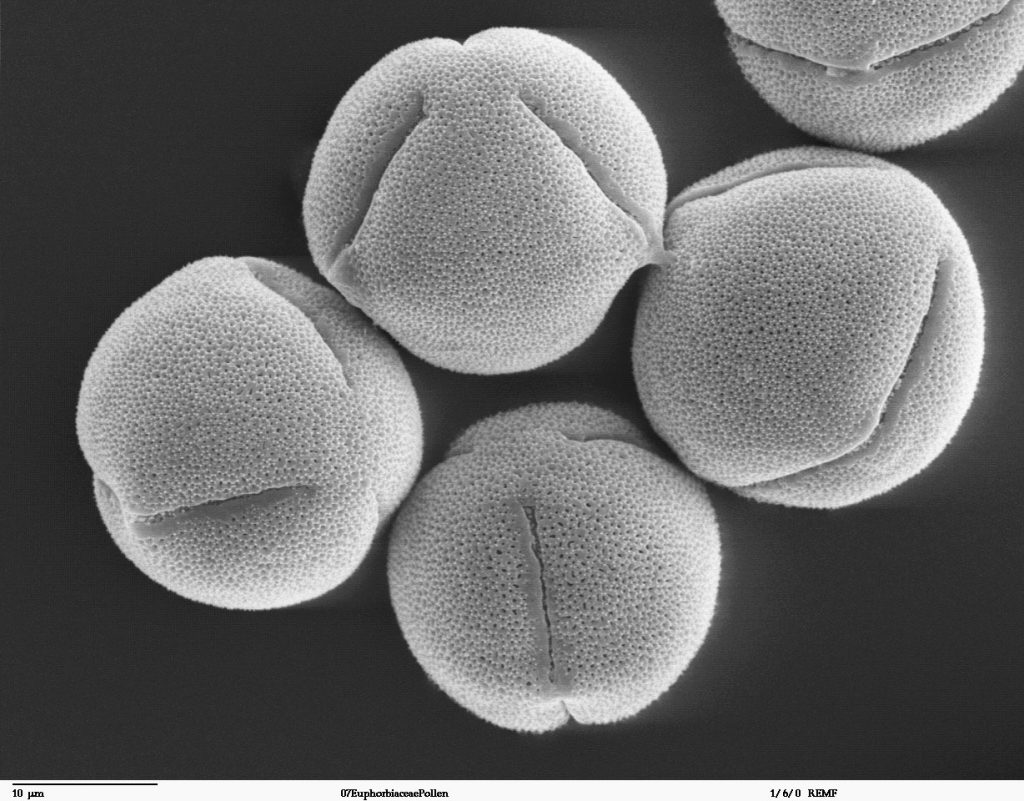

The fantastic variability that we see in the flowers growing around us hides a marvellous secret known to only a few. While we breathe in aerial pollen grains with every inhalation, few of us are aware of the remarkable shapes in this genetic dust. The geometric form of pollen – the male part of the higher plants – is as strikingly beautiful as the plants from which they come.

The flowering plants are amongst the most diverse and extensive living things on the planet. With the other seed plants, such as the conifers and the cycads, they form pollen that is spread throughout the world. The ability of plants to colonise and survive in new habitats comes from the rapidity with which these populations can develop new lifestyles and strategies.

The engines driving this speed are the new combinations that appear when two individuals share their genetic blueprint. Sexual reproduction creates novelty at a far greater speed than the random mutations that occur in asexual reproduction, and pollen is the mobile agent that travels between the plants.

Pollen, like animal sperm, originally evolved within watery environments, but has now adapted to a terrestrial world. Two hundred million years ago, the land was covered by plants that used the wind as a transport mechanism for their mating, but in the last 65 million years, the flowering plants have come up with a far cleverer method.

The pollen of the flowering plants takes advantage of the innumerable insects and, to a lesser extent, the birds and mammals. These animals visit the flowers to consume the pollen or a gift of nectar, and the plant takes advantage of the opportunity to dust these visitors with the pollen.

With scanning electron micrography, humans have finally been able to glimpse this hidden world. Different groups of plants have different shapes for their pollen, and they are marvellous – spiked spheres, orbs with evenly spaced apertures, three-lobed stars, curved plates, and polygons beyond description.

The identification of pollen has become a useful tool in determining past environments and solving modern mysteries. The mud at the bottom of lakes accumulates pollen from the vegetation nearby, and can therefore record changes in vegetation over hundreds or even thousands of years. Within rock layers, ancient pollen can also be extracted, providing a sense of plant communities at a distance of millions of years.

Pollen identification has helped archaeologists to determine ancient human activities and environmental changes, and as a forensic tool to determine facts within a crime investigation. And, as any allergy sufferer will tell you, the daily pollen counts published by meteorological organisations are a constant reminder of the presence of this sometimes-mischievous powder.

These beautiful grains are almost impossible to see with the naked eye, but pollen dusts the surfaces of our environment and the air we inhabit. They are the method by which the green world adapts to a dynamic planet.

For more stunning stories and photographs from this issue, check out Asian Geographic Issue 111.