Storms of dust and sand

By YD Bar-Ness

I stood on the balcony in New Delhi, looking towards the horizon as a dark cloud swooped towards the megacity. When it finally arrived minutes later, I raced indoors to escape.

Despite shuttered windows and closed doors, a thick layer of dust collected on every surface, decorating everything in the apartment with a fine grey powder. Relieved that I was safely indoors, I wondered what this strange silt was, and where it had come from.

Was this the sands of the Sahara? Or the precious topsoil of another nation?

From Dust We Are Made, to Dust We Will Go

There exists in the atmosphere a fantastic mixture of microscopic particles. With each indrawn breath, you bring into your lungs the fine dust that is suspended in the air: traces of minerals, petrochemical haze, wood smoke, plant pollen, skin flakes, ocean salt, bacteria, road tar, heavy metals, plastic vapours, moss fragrance, fungal spores, and more.

There is a staggering and unimaginable variety to these atmospheric particles and yet our lungs constantly filter out most, if not all, of this airborne dust. Sometimes, however, it can accumulate into atmospheric streams and become an awesome natural phenomenon – a dust storm. When the weather, terrain and human activity conspire, these thick storms can choke and blind. Such events are often utterly terrifying.

Natural dust and novel chemistry

Dust storms can be small and localised, but they can also transcend national boundaries and illustrate some of the more extreme dynamics of the landscape. They are natural phenomena associated with drier and less-fertile parts of the world, but their severity and composition can be drastically affected by our land management.

The population centres of Asia are most often dusted by the vast Sahara Desert of North Africa, and the dry upland plateau of Mongolia. Winds blowing from West to East can pick up sand grains, eroded soil, salt evaporites and other sediments, and take them on a long aerial journal to the lungs of some of the world’s largest cities.

Poor irrigation practices and intensive farming have been implicated as worsening this dynamic. The phrase “Dust Bowl” was used to describe the nightmarish storms in the 1930s triggered by the clearing of the native vegetation of the North American Great Plains. Besides the haze and storms affecting people downwind, it’s important to remember that those upwind are losing life-sustaining and irreplaceable soil.

Loess: The fertility of the wind

In some regions of the world, the fertile soil actually arrives on the wind. Known as “loess” (cognate to the English word “loose”), it is found as massive soil layers on the Huangtu Plateau of the Yellow River of China. The river itself is named after the colouring of this wind-borne material.

Loess is also found in the American Midwest and Central Europe. These deposits, however, arrived over long time-spans, measured in the hundreds or thousands of years. While they may provide or receive the dust from storms, they are a product of a relatively stable dynamics rather than particular storm events.

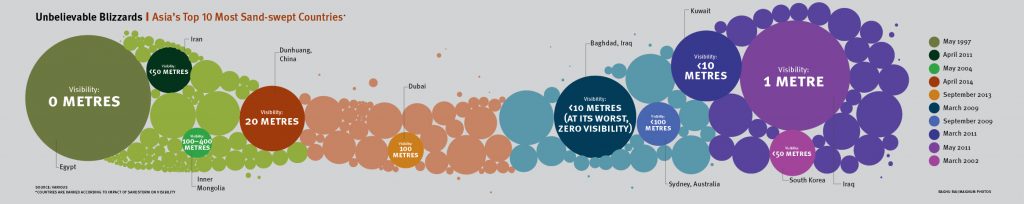

Asian dust storm dynamics

Two major storm pathways are responsible for the largest and most prominent dust events in Asia (although dust storms can occur on much smaller scales). The southern pathway begins as Atlantic winds sweeping over the vast Sahara Desert and collecting sand grains. It can accumulate as a dust storm, which visits, and sometimes builds strength, in the dry areas of Arabia and Iran before continuing over Pakistan and India. Satellite imagery now allows us to observe the path of this airborne material over long distances. When the storm I experienced hit Delhi, it was a distinct thing from the daily haze of motor-vehicle emissions and had very possibly travelled hundreds or thousands of kilometres.

The other Asian storm pathway that brings dust into densely populated areas begins as cold winds in Siberia, and pushes across the desert areas of Mongolia and China. It then continues its voyage eastward, bringing blizzards of fine dust and artificial pollution to the eastern seaboard of China and the cities of Korea and Japan, and then onwards into the Pacific.

We are all downwind

While the natural materials in a

dust storm are the most abundant, an aerial stream of dust can also deliver artificial pollutants. Humanity has brewed up a potent cocktail of chemicals and radiation, and these are being transported far from their point of utility.

This air pollution is uncontrollable and controversial: Dust storms can begin in one country, travel across another and bring a toxic dusting to yet another. Like issues of water pollution, these circumstances are especially difficult for those on the receiving end. Unlike water pollution, though, air pollution is impossible to channel. Ultimately, we are all downwind of someone else’s industry, and we all breathe the same planetary atmosphere.

The dust can travel even longer distances and have unexpected impacts. Saharan dust has been found on the ice in Greenland, in the forests of the Amazon and covering the corals of the Caribbean.

Dust also plays an ecological role in distributing terrestrial nutrition into the oceans, where it promotes the growth of phytoplankton. Earth’s dust dynamics are a complex and poorly understood part of our natural world, and dust storms are merely the most noticeable phenomena.

Take care if you are in the path of such a storm, but also marvel at its energy – dust surrounds us, and with each breath, it is within each of us.

For more stunning stories and photographs from this issue, check out Asian Geographic Issue 109.