Text and Photos Tripp Burwell

“No, no. You go first,” I exhaled, as I hauled myself up another knife-sharp limestone boulder.

The Indian Forest Officer, carrying a loaded gun, heaved himself up and around me. He had slipped while clambering up the limestone face, barely catching himself. I ushered him ahead.

Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk! The slow three-beat staccato continued to draw us onward. We had started at dawn with a few dozen men. Finally, we were reaching the source of the sound. Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk! All the male villagers in Kosi Gittim (gittim meaning “village” in the local Garo tongue) looked to me for the next move. Shrugging my shoulders, I simply pointed towards the noise as it rippled through the forest on the edge of Balpakram National Park. Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk!

We continued slowly. The men in front paused behind bus-sized boulders, lest we were seen too early by the loggers. Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk! Yet around every corner, we only saw more empty forest. Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk! Cut logs lined the path, waiting to be transported down the stream bed to nearby Bangladesh, whose minarets called to us in the still evenings of the dry season.

First one man, then another, turned back from a hilltop. Stage whispers floated down a ridge where our previously strung-out group had pooled together. Thwunk! The men of Kosi shouted. Thwunk! There was no third axe stroke this time, only the loud flow of our group charging clumsily over boulders and the sound of sandals swishing across leafy forest floor as the shocked loggers sprinted from our nervous advance.

“Have you ever bought firewood?” Kamal Medhi asked the group of men huddled around the fire. Everyone in Kosi Gittim laughed. Who would buy firewood? All the firewood the village could ever need grew within a short walk of the gittim.

“Five, 10 years ago, how many streams did you have?” Kamal continued. The laughter eased as members of the gittim pondered the question over lips bulging with gui, or a red paste made from areca nut. They concluded that the village had had nine permanent streams, all of which now only bore water during the height of the wet season.

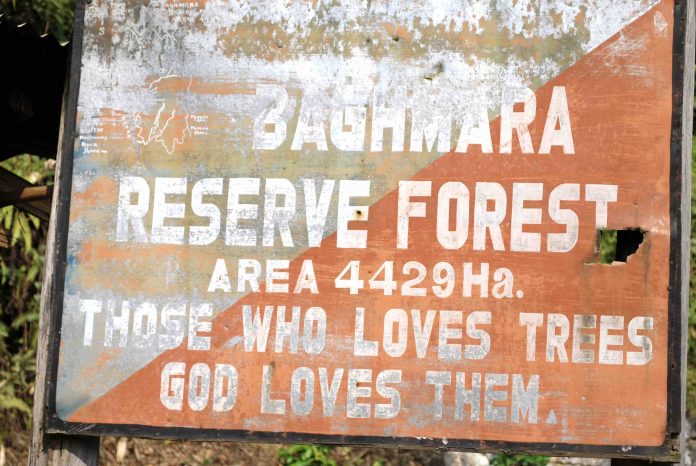

Kamal nodded; he knew this refrain. Kamal was a Field Manager for Samrakshan Trust, an NGO working to encourage environmental conservation throughout India. The Indian government had promoted orchards for soil conservation and income generation. It was a good idea for some areas, but in places like Kosi Gittim, turning jungle to orchard could create more problems than it solved. Kosi Gittim lies in northeast India, outside Balpakram National Park in the state of Meghalaya, two long bus rides away from the closest major airport in Guwahati, Assam.

I had come from the US to teach the Samrakshan staff how to map forest cover. One of the first steps in saving the jungle is to determine where it still stands. We visited gittims around Balpakram, showing maps of the area, laced with blue lines of stream beds. Concentric circles tightened around the tops of hills. Demonstrating our position on the map – “Do you see this hill here?” – we would ask members of the gittim about how they used the land. “Where is your forest? Where are your orchards? Can you draw it for us?”

Kamal and I hoped to link community education with our mapping for a broader impact in the gittims. Explaining the connection between deforestation and the depletion of water resources, Kamal told members of the gittim, “We must ask ourselves why our streams are drying up.” They replied, “Not enough rain.” Kamal pointed out that the rain had remained steady in recent years, while the number of trees around the gittim had decreased significantly.

“It happened to us in America as well,” I chimed in. “We cut down too many trees too fast and our rivers either ran dry or flooded. It has taken us many years to recover. In some places, we have still not recovered. We did not take responsibility for our land.”

After much discussion about the concepts of run-off, the men of Kosi agreed that there were far fewer trees, which might be related to the poor quality of their streams. However, they attributed the greatest tree loss to an illegal Bangladeshi logging ring, which had plagued the area for several years. Kamal had heard this deflection before. Though Kosi was on the Indian side of multiple layers of barbwire border fence, it sat just uphill from Bangladesh. Disdain towards the Bangladeshis, who are uniformly Muslim and generally poorer than the mostly Christian Garos, was common. Rather than argue with the Kosi residents about the source of the gittim’s resource depletion, Kamal countered, “Do the Bangladeshi loggers irritate you? It’s like someone stealing your property while you are asleep. Do you want to stop it? If you want to stop it, we want to help.”

Murmurs of agreement slowly crawled around the fire. The nokma, or headman, consented. A long conversation ensued, detailing the ways in which the men of Kosi would seek retribution upon the Bangladeshis the next morning.

While the sun still floated low above the trees, all the men of the gittim arrived at the house of the nokma. Before we set off, the local Forest Officer joined our hearty group, feeling it his duty to be present for such an occasion. The laughter and noise of the excited men sprang ahead of us. We tried first one path, then another, not knowing quite how to locate members of an illegal logging ring on the edge of a dense national park.

Late in the morning, we reached a string of squarely trimmed logs, ready for transport. Black, ashy remnants of small fires freckled the path’s brown dirt. We had found a hopeful trail at last and began to slide carefully around boulders to follow it. Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk! Everyone paused. Thwunk! Thwunk! Thwunk!

The 25th anniversary of the largest and longest running dive show, Asia Dive Expo (ADEX) is set to occur on the 11-14th April 2019. Centred on the theme – Plastic free Future, ADEX is more than just a dive show with its commitment to the environment. Among an exciting lineup of programs, attendees can look forward to a Future Forward Series of Panel Discussion on the Single-Use Plastic Conundrum in Asia, on 13th April.

So join us at the event, get inspired and for all you know, you might just liberate the inner diver in you! More details of the event here.

For the rest of this article (Asian Geographic No.107 Issue 4 /2014 ) and other stories, check out our past issues here or download a digital copy here