(Text and photos: Boaz Rottem)

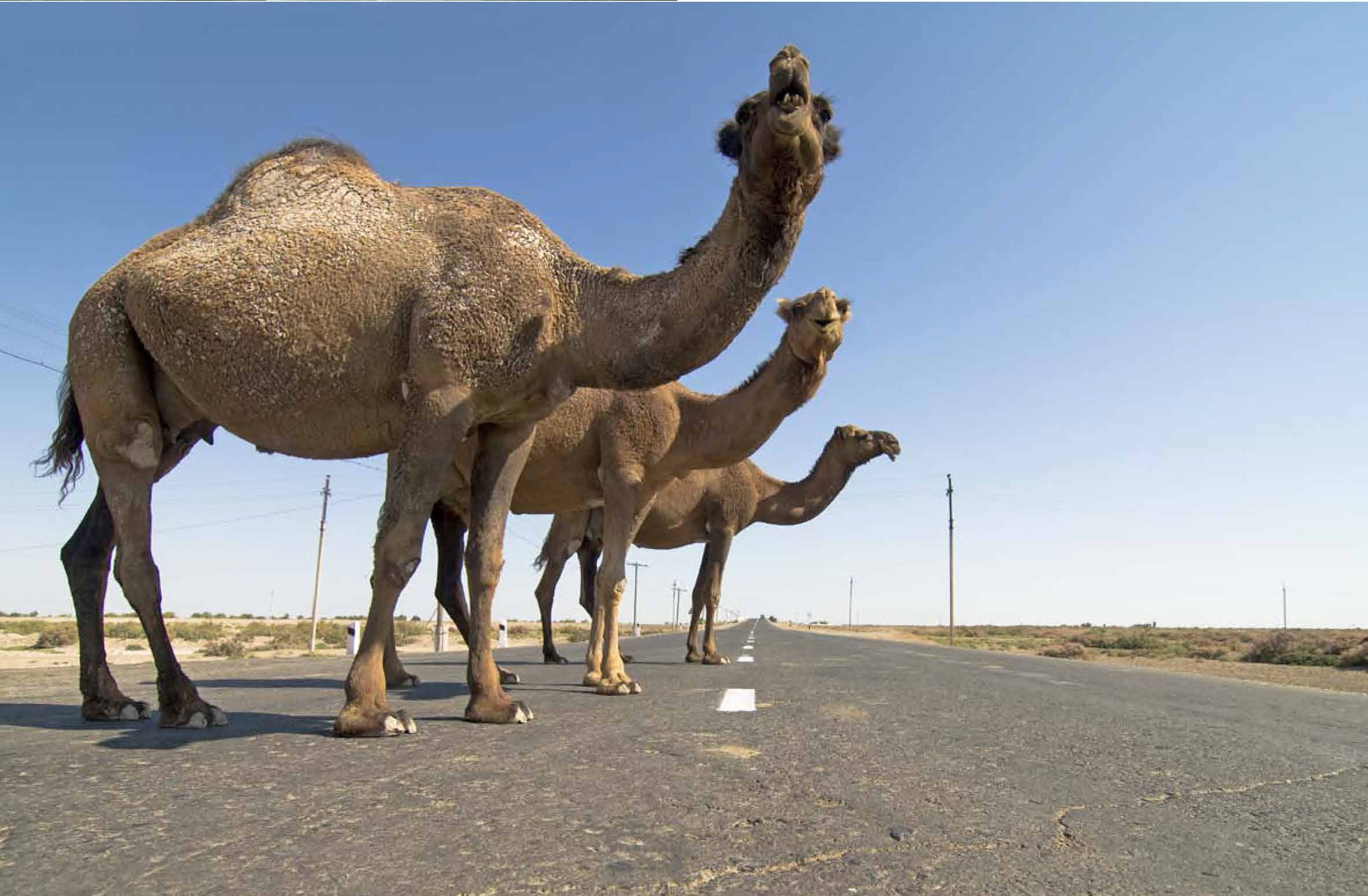

EARLY MORNING. A clear autumn day. The arid climate is palpable. Seated in the back of a brand new Uzbek-made Korean car, we are driving along the straight road that leads to the town of Moynaq, smack in the middle of the now-parched seabed of the Aral Sea. This deserted town in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic of Uzbekistan, is infamous for being the “boat graveyard” for the rusting fishing vessels that once plied the waters of the once-abundant sea. The vastness of the Kyzyl Kum desert spreads for many kilometres on both sides of the road, with the occasional herd of camels crossing the asphalt to get to better feeding grounds.

After two hours in this desolate wilderness, a sign for the fishing town of Moynaq indicates that we were close. A short time later, a billboard welcomes us to this remote place. The huge sign, slowly deteriorating, is a reminder of Moynaq’s heyday, when it was a flourishing fishing town. It is now but an empty shell, a ghost town, forgotten in time and space. I am headed for the other side, towards the shores of the Aral Sea.

Hearing about the disaster is one thing, but seeing it with your own eyes is a completely different experience. The dramatic view doesn’t disappoint: a vast expanse of earth, dried up and formed into an irregular crust, littered with decaying metal giants. Fishing boats, big and small, stand abandoned in what used to be the port.

I descend onto the parched seabed for an unforgettable walk between these stranded beauties. It is a poignant moment. It seems like the boats are waiting – but for what? I’m reminded of a quote by humorist Don Marquis: “What man calls civilisation always results in deserts.”

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE ARAL SEA?

The Aral Sea is – or was – actually not a sea at all. It was an immense lake, a body of fresh water that was once the world’s fourth largest lake. But in the last 50 years, more than 85 percent of the lake has disappeared.

In the 1960s, the Soviet Union undertook a major water diversion project on the arid plains of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The region’s two major rivers, fed by snowmelt and precipitation in faraway mountains, were used to transform the desert into farms for cotton and other crops. Before the project, the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya rivers flowed down from the mountains, cut northwest through the Kyzyl Kum desert, and finally pooled together in the lowest part of the basin to form the Aral Sea.

While the irrigation project made the desert bloom, it devastated the Aral Sea. The Northern Aral Sea (sometimes called the Small Aral Sea) separated from the Southern (Large) Aral Sea. The Southern Aral Sea split into eastern and western lobes, which remained tenuously connected at both ends.

In 1965, the Aral Sea was receiving about 50 cubic kilometres (or 50 trillion litres) of fresh water per year. By the early 1980s, that number had fallen to zero. As a consequence, concentrations of salts and minerals began to rise sharply in the shrinking body of water. This change in chemistry led to staggering alterations in the lake’s ecology, causing precipitous drops in the fish population.

The Aral Sea supported a thriving commercial fishing industry employing roughly 60,000 people in the early 1960s. The fish harvest had been reduced by 75 percent by 1977, and by the early 1980s the commercial fishing industry had been eliminated. The shrinking Aral Sea has also had a noticeable affect on the region’s climate. The growing season is now shorter, causing many farmers to switch from cotton to rice, which demands even more diverted water.

By 2001, the southern connection had been severed, and the shallower eastern part retreated rapidly over the next several years. Especially large retreats in the eastern lobe of the Southern Aral Sea occurred between 2005 and 2009, when drought limited and then cut off the flow of the Amu Darya. Water levels then fluctuated annually between 2009 and 2012 in alternately dry and wet years.

As the lake dried up, fisheries and the communities that depended on them collapsed. The increasingly salty water became polluted with fertiliser and pesticides. The blowing dust from the exposed lakebed, contaminated with agricultural chemicals, became a public health hazard. The salty dust blew off the lakebed and settled onto fields, degrading the soil. Croplands had to be flushed with larger and larger volumes of river water. The loss of the moderating influence of such a large body of water made winters colder and summers hotter and drier.

Read the rest of this article in No.95 Issue 2/2013 of Asian Geographic magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.