Text Sophie Ibbotson & Max Lovell-Hoare

Every carpet tells two stories: the story the carpet weaver intended and the story of the carpet weaver himself. Both of these stories are told with knots, not words, and the finest Persian carpets can contain as many as 1,032 knots per square inch (kpsi). If you examine the carpet under a magnifying glass, you will see each one of these knots, each made by hand, but it is only when you step back and survey the carpet from a distance that you can appreciate the complete design.

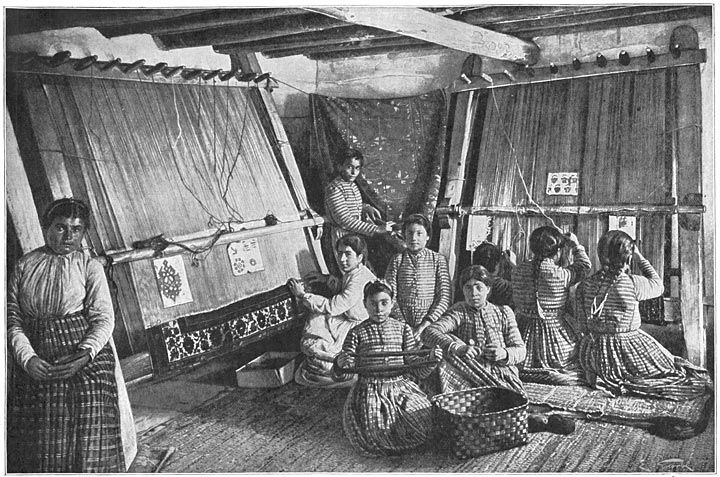

The complex art of carpet making using knots dates back some 2,500 years and it spread along the Silk Road from ancient Persia to India, Afghanistan, Central Asia and China. Working on simple looms, artisans made their carpets from silk and woollen threads, and then as now, a skilled weaver would hand tie and cut approximately 12 knots per minute. Even at this speed, it would therefore take four to five experienced artisans working six hours a day, six days a week over 14 months to complete a nine by 12-inch rug with 500 kpsi! Designs with a limited colour palette are faster to weave than those with a range of colours, and of course the more kpsi, the longer it will take to finish the final design.

Carpet making has always been a family business, with children assisting in the process from an early age and learning the craft as they grow up. Precision, speed and a flair for design are all important skills to learn and set a master craftsman apart from the rest.

There are two main forms of carpet design, nomad and city carpets. The designs of nomad carpets come from the imagination of the carpet weaver: although he might have a design in his head, he has nothing written down and can change his mind as he works. For this reason, you’ll usually find repeating geometric designs or floral motifs, a range of colours and shapes. There can be significant variation in the designs, even within a single carpet, as the artisan weaves what he feels like, and despite years of experience and plenty of care, the workmanship is not always consistent. Flat-woven carpets such as killims inevitably fall into the nomad category, but so too do some knotted designs.

City carpets are an altogether more formal affair, as the carpet weaver works from a prescribed pattern. The number of knots in a row, and the specific colour of those knots, is laid down on paper as a series of numbers, and the weaver translates each line of code as he works. It is a no less remarkable skill to be able to dream up a carpet design and to write out the code in the first place. This detailed planning, which may involve more than one carpet designer and maker, enables the creation of far more complex and accurately executed designs, and the quality of the final carpet consequently tends to be finer.

Though few carpets are signed or dated, that is not to say that the weaver can’t leave his mark, and there are differences between the work of individual artisans, as well as between regional carpet-making schools. The choice and quality of materials, including the types of dyes, have a substantial impact on the appearance of the finished carpet, as well as its durability. There are carpet weavers who deliberately weave symbols or specific marks into the carpet, regardless of the specified design, so that even centuries after their demise, it is possible to identify their work.

For more stunning stories and photographs from this issue, check out Asian Geographic Issue 110.

For more stunning stories and photographs from this issue, check out Asian Geographic Issue 110.