The natural heritage of Japan’s cedar trees

by YD Bar-Ness

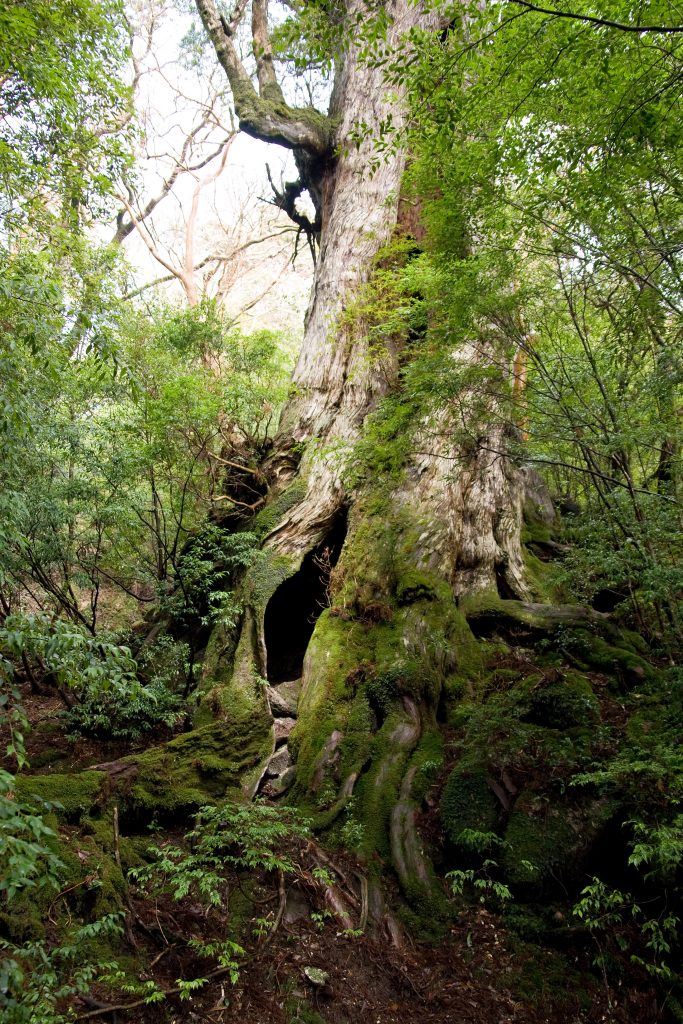

The ancient Yakusugi trees of Yakushima are amongst the very oldest and largest of Asia’s living things. These evergreen cedars can be found on the circular island of Yakushima, lying near the southern tip of the Japanese archipelago with a mountainous interior that is mostly forested wilderness. These World Heritage-listed groves, called Cryptomeria japonica, are the national tree of Japan and are nestled within the valleys of these hills.

Known locally as Sugi, the colossal trees on Yakushima are given the additional honorific of Yakusugi. These ancient conifers, lasting for millennia, have witnessed and survived immense changes of history from their isolated island home. In a country known for its gleaming skyscrapers and electronic industry, they provide a living link to a lost wilderness past and are the pillars of the archipelago’s most magnificent forest.

An evergreen interior

One arrives in Yakushima by boat from the southern port of Kagoshima, passing close by the active volcanoes of Sakurajima and Kuchinoerabu-jima to arrive at the northern coast. The mountain peaks tower two kilometres above, and are almost always clad in a thick veil of cloud. Exposed on their slopes are sculpted sweeps of weather-worn granite – continental rocks uplifted from below. These are quite young in geological time – only 15 million years – but still far older than the restless volcanoes nearby.

Yakushima is one of Japan’s wettest places; the wet valleys of the mountain slopes are drenched with 10 metres of rainfall annually and autumn brings powerful typhoons. The forests have the dark emerald colour of cedar scales, moss and ferns, and this evergreen interior lies between the alpine fields of the high plateau and the lush coastal jungles. Taken together they represent the best remaining example of Japan’s altitudinal ecological gradient.

As you walk, bike or drive up into the hills from the coastal palms, banyans and sugarcane trees, the subtropical jungles become cooler and mistier. You’ll soon get your first views of the Yakusugi – tall trees with a rich brown bark, deep green needles and a crisp smell.

Like the true-cedar trees of the Himalaya or the red-cedars of Taiwan, they are the most recognisable forest giants in a region of remarkable biodiversity. While sometimes confused with the true pines, the Pinaceae, the Yakusugi are part of the cypress family Cupressaceae. This group includes the very tallest and oldest living trees on earth, and is found from coastal deserts to high mountains. In a world where things change at ever-increasing speeds, these evergreens remind us of a slower, more methodical way of life.

Elders of the forest

This species – Cryptomeria japonica – is familiar to citizens of the country as a beloved tree of temples and plantations. Across eastern Asia, Cryptomeria trees are grown for their aromatic, rot-resistant timber and are known to bring solitude and serenity. Unfortunately, the vast quantities of pollen have brought misery to many Japanese in the form of allergic reactions. The swollen eyes and hay fever of kanfusho afflict one in five Japanese people.

On Yakushima however, people come to see the remaining elders of the forest. Many of these have been given names and are well-known across the country. The most famous of these, Jomon Sugi, is named for the prehistoric period of Japanese archaeology beginning 100 centuries ago through to 300 BC. This tree is widely recognised as Japan’s oldest, and various estimates range from 3,000 through to 7,200 years. Other giant Yakusugi, such as Yayoi Sugi and Kigen Sugi, are more reliably estimated to be three millennia old, making these amongst the very oldest of living things on earth.

Protecting a national treasure

The Yakusugi trees have not always been protected. In the 1500s, harvesting of these trees began and timber was shipped to the mainland as a valuable commodity. The rot-resistant wood was highly prized for roofing shingles, temple structures and boat-building. In those days, immense effort was required to fell and transport a tree and despite constant demand, there were still some areas of uncut forest remaining by the start of the 20th century. In 1923, large parts of forested interior were declared a National Monument, and in 1964, a National Park.

However, the forests remaining outside of the Park were then threatened by the most dangerous technology yet – the chainsaw. Only a fifth of the forest remained uncut. In 1979, a typhoon triggered 150 landslides across the island – all of them occurring at areas that had been cut. This clear linkage of cause and effect triggered local public outcry against clearing of the virgin forest, but it would be another three years before the Tokyo-based National Forestry Agency would be convinced. In 1982, the remaining old forests were set aside as a scientific reserve, and in 1993, Yakushima’s forest became the first of Japan’s World Heritage listed properties. It is now the premiere eco-tourism destination within Japan, and the standing trees are valued highly as living things.

Yakushima holds a special place in the fabric of modern-day Japan and the global forest, and is of great value for tourism, conservation, history and culture. Because of its rarity in its natural forests, Cryptomeria japonica has been listed as Near-Threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

In the popular anime film Mononoke-hime, or Princess Mononoke (1997), the cool forests of Yakushima were portrayed as a magical forest of gods, beasts and spirits. In Japanese, the spirit of the tree is known as kodama and in the ancient Sugi forests of Yakushima, they are protected and revered as a pillar of the Japanese natural world.

For more stories and photos, check out Asian Geographic Issue 115.