(Text by Matt Bile. Illustrations by Bill Rebsamen)

LIFE exists on Earth because of the sea. Life awoke in the sea, reached its greatest diversity in the sea, and conquered the land by crawling from the sea. Since the first primitive humans beheld the oceans, we have wondered at their secrets and the life hidden within their 1.3 billion cubic kilometres of water.

One thing scientists agree on is that we still don’t know all about such life. According to the 10-year Census of Marine Life (CoML), which reported on 6,000 new species and estimated that there were hundreds of thousands more, we don’t even come close.

The majority of still-undiscovered species probably lie in what we may call the Old World Seas, the waters fished and traversed by the oldest human civilisations. The Pacific and Indian Oceans, along with the Red and Mediterranean Seas encompass some 245 million square kilometres. The peoples living around the Old World Seas have always known they held countless fishes and other animals: some well-known now, but also some of whose existence we have only hints and legends.

Species found in this century include a new sponge and a new crab off Singapore, a new genus of shrimp near Sri Lanka, and a lighted 70-centimetre squid from Indian waters. Indonesia’s Ambon Bay yielded a psychedelically coloured frogfish that hops on its fins, while the furry-looking “yeti crab” was found near the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge.

Madagascarene waters yielded a huge (four-kilogramme) lobster, and a “Jurassic shrimp” thought extinct for 50 million years was caught in the Coral Sea. By one count, 100 new marine fishes turn up worldwide every year, and five new marine invertebrates are discovered every day.

The pursuit of new or presumed-extinct animals includes the controversial subspecialty of cryptozoology – the study of “hidden” animals. All biological scientists look for new species, but cryptozoologists look for clues in a broader variety of references, including myths and legends as well as modern sightings, and are willing to investigate some animals most scientists think are fanciful.

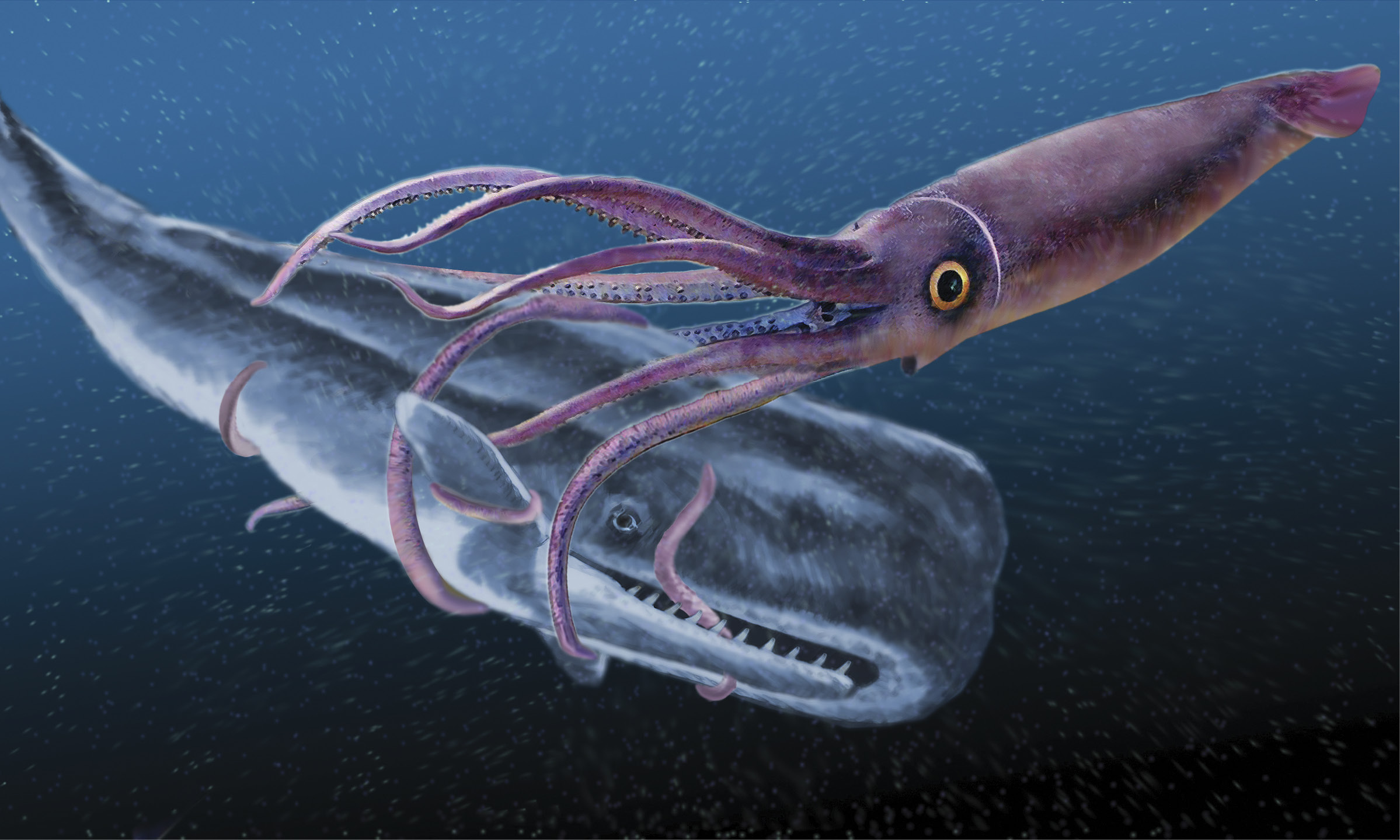

The giant squid and colossal squid were once dismissed as myths, and this is understandable: they may measure 15 metres or more (perhaps much more) and are so strange they could easily be pictured in the seas of some alien planet.

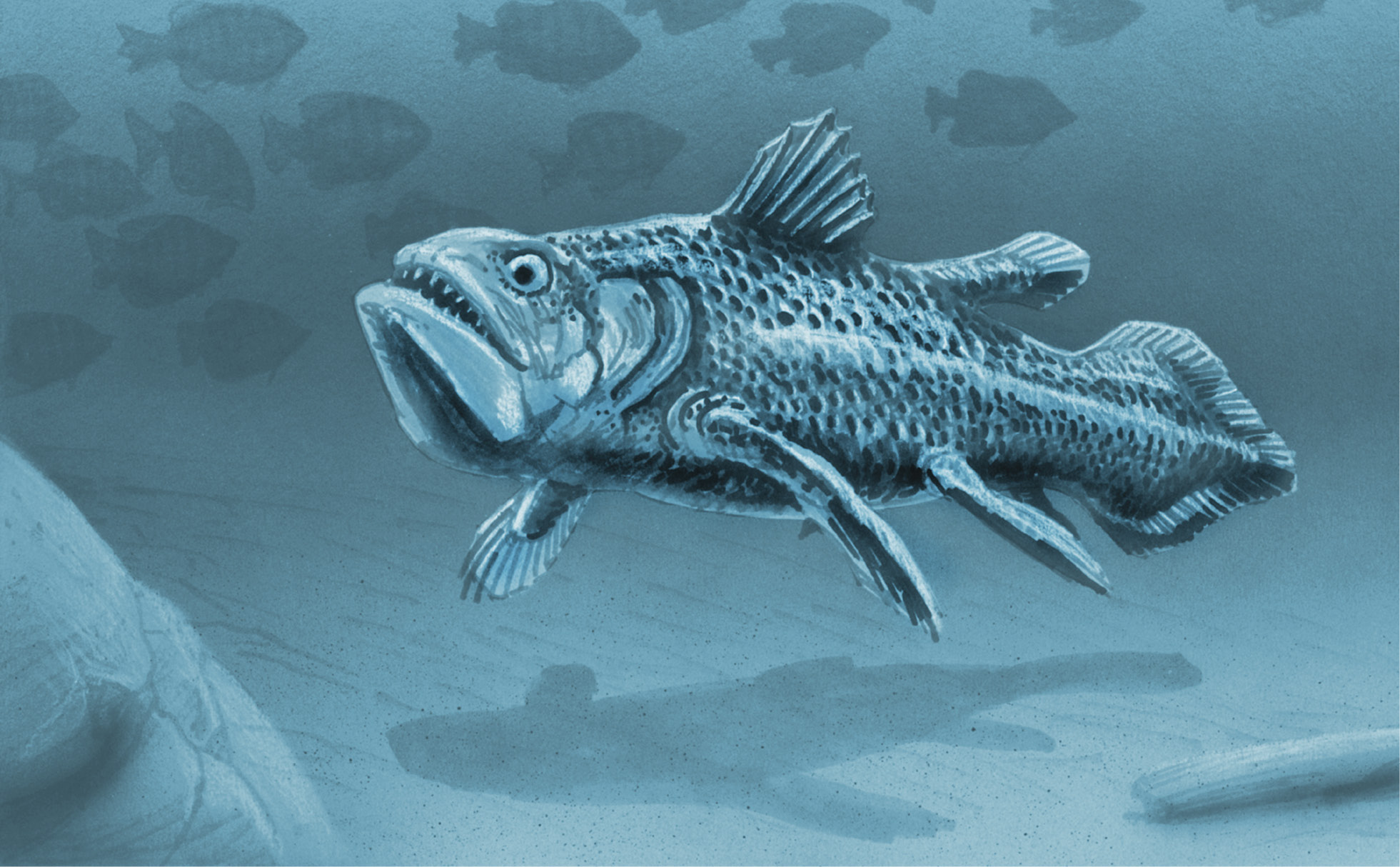

The most famous discovery of the past century was the coelacanth, collected from the western Indian Ocean in 1938. This chunky fish astonished scientists because the youngest known coelacanth fossils dated back 60 million years. In 1998, a second species of coelacanth was discovered in Indonesia. After two visiting scientists saw a coelacanth being taken to market on Sulawesi, a search began that ended when fisherman Om Lameh Sonathon delivered a live specimen of the fish known locally as rajah laut – “king of the sea”.

In 1998, scientists found a huge jellyfish, a metre across and coloured a striking blood red, in a marine canyon off California. This came only a year after the description of the similar-sized Chrysaora achlyos, a surface dweller whose metre-wide bell supports pleated oral arms extending seven metres and tentacles trailing well beyond that.

Still awaiting a scientific name is the bizarre squid, over six metres long with huge terminal fins and long, slender tentacles with “elbow” bends, videotaped at depths over 2,000 metres in the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans.

Nothing in the sea is stranger than the mimic octopus, a small cephalopod discovered off Sulawesi. The species can arrange its entire shape, texture and colour to mimic a stingray, a flounder, a starfish, a jellyfish, a sea snake, an eel, a lionfish or a baby cuttlefish. It is one of an estimated 150 new species of octopus collected in this region in just the last decade.

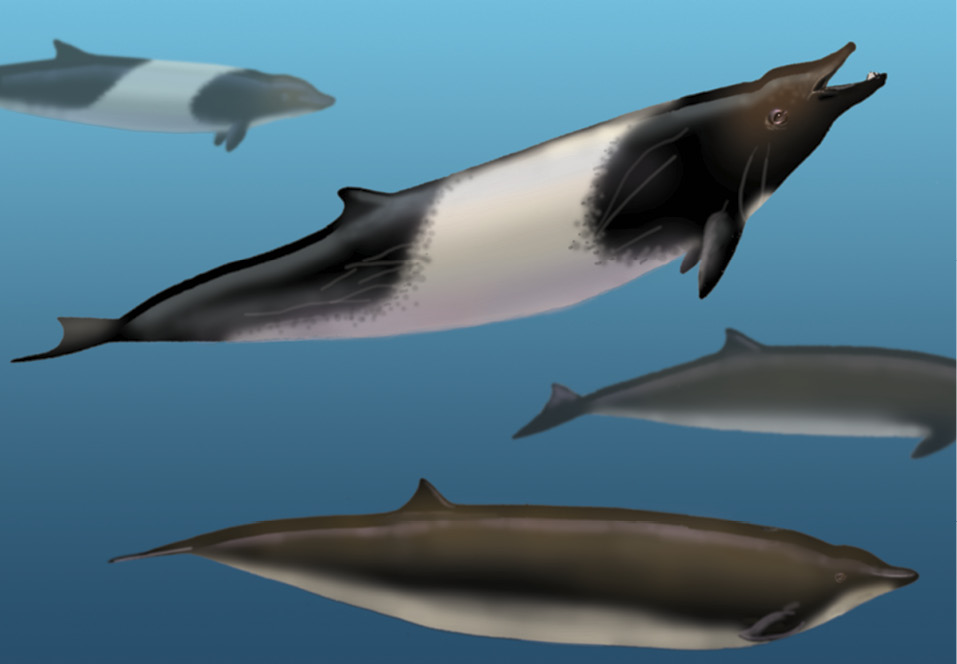

Discoveries and mysteries include some very large animals. For decades, the Indo-Pacific beaked whale (or Longman’s beaked whale) was known only from two skulls. Cetologists knew nothing about it until 2003, when sightings and stranded specimens were matched to the original skulls to confirm a new cetacean, seven metres long. Also in 2003, a Japanese team announced that whales from the Solomon Sea and the eastern Indian Ocean, thought to be unusually small fin whales (about 10 metres), were in fact the new species Balaenoptera omurai.

The hulking five-metre megamouth shark, caught in 1976, seemingly sprang from nowhere: there were no fossils, no reports of sightings, not even folklore about this deep-water species. Rafters on the 1947 Kon-Tiki expedition watched luminescent, oval forms 10 metres long circle beneath them without ever surfacing or giving a clue to their identity. Still unidentified is the fish two American oceanographers saw from a submersible in the San Diego Trough in 1966. This was described as 10 metres long with a rounded tail and “plate-sized” eyes.

There is no doubt the waters of the Old World Seas still hold undescribed species, many of them sizable and some likely to be spectacular. Could they include some “monsters” from legend? We don’t know.

What we do know is that conservation and wise use of marine resources demand we keep up our efforts to learn what is out there. The first rule of conservation is to know what it is you are trying to conserve. In a world of which we know only so much, the next discovery is always imminent, and new wonders of the sea are still awaiting us. AG

For the rest of this article (Asian Geographic No.78 Issue 1/2011) and other stories, check out our past issues here or download a digital copy here