(Text by Khong Swee Lin. Photos by Carl-Bernd Kaelig)

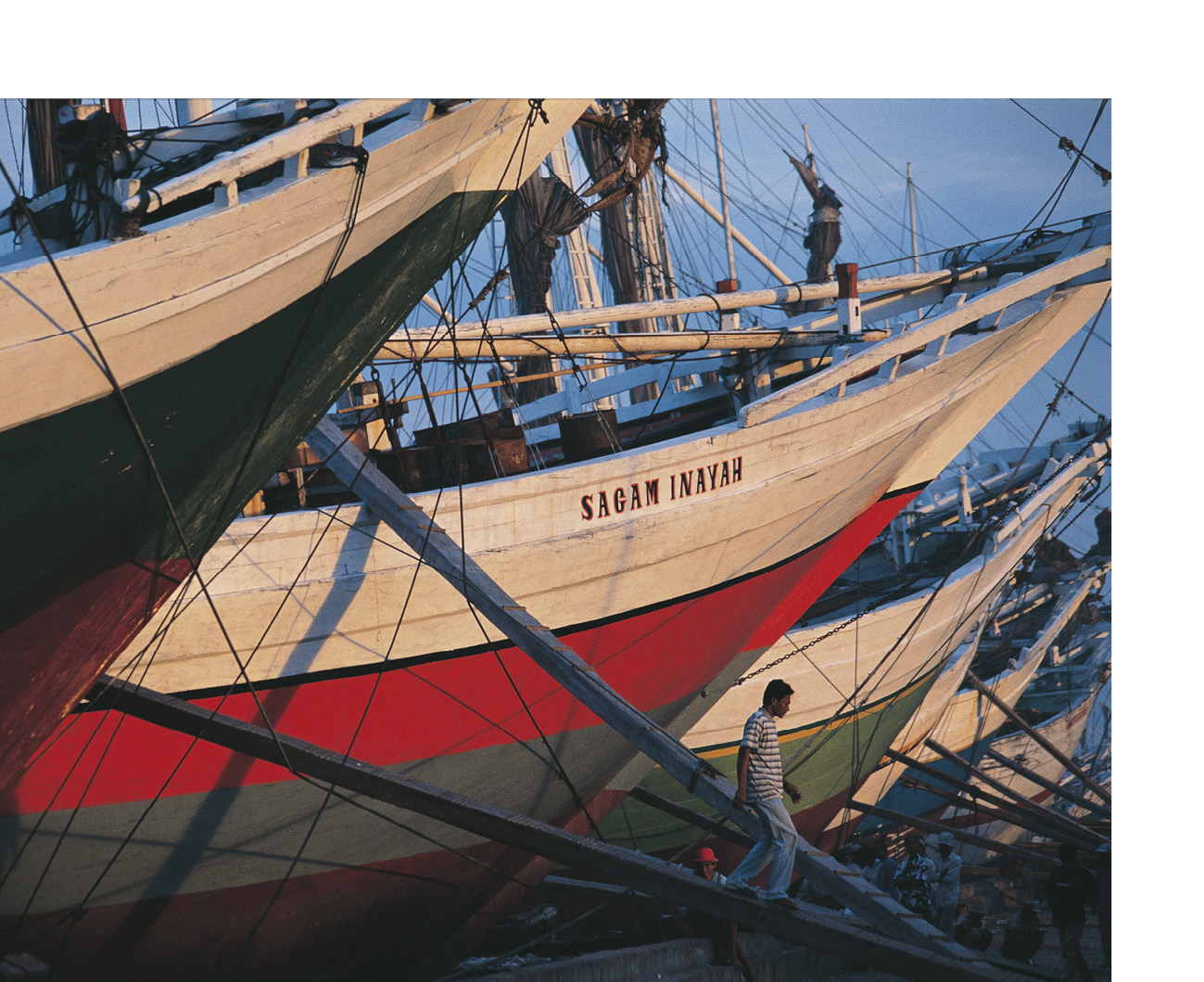

WORKING round the clock, stevedores trot up and down narrow gangplanks propped between port and deck, loading the holds of an armada of Buginese schooners commonly known as pinisi thronging the old harbour of Sunda Kelapa on Jakarta’s north coast. With double masts thrusting skywards, their sleek prows raised jauntily, they wait to be filled with treasures – perhaps electronic goods or just prosaic sacks of rice or cement – before gliding off on the warm waters of the Java Sea.

Accomplished seafarers since time immemorial, the Bugis have sailed the Seven Seas and more, venturing as far as China and even Madagascar without the benefit of compass or sextant and relying only on the stars, the winds and the drifts of the sea. Seamen, adventurers, warriors, slave runners, pirates – the feared and revered Bugis were all these exotica and more; also astute merchants, as Singapore knew them to be. Their trading craft (with distinctive rectangular tanjaq sails), known as padewakang, once fronted the beach at where else but Beach Road in Singapore, a stone’s throw from a street that pays homage to their maritime traditions – Bugis Street. As late as the 1980s, it was still possible to catch sight of a Buginese schooner off Singapore’s east coast.

And what would a sailor be without his boat? Due homage must also be paid to the master shipwright and craftsmen of South Sulawesi whose meticulous handwork enabled and encouraged their compatriots to blaze new watery trails. The palm-fringed beaches of Tanah Beru on the most southern coast of South Sulawesi have been and remain the birthplace of many a Buginese schooner.

The Latin term pinus or pinnasse in Dutch was adopted by the trading ships of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) that plied the trade routes between Holland and the East from the 17th century onwards. About 35 metres long and 8 metres wide, the pinisi typically had twin masts rigged with seven sails and two side rudders weighing between 50 and 200 tonnes. They would have a lifespan of roughly 40 years.

In the 18th century, the VOC began to build their ships in the local shipyards, paving the way for change in the maritime industry. Later, other entities followed suit, building in the Dutch style as the new style proved swifter than the traditional indigenous vessels. Modifications and combinations were tried and tested. As long as the best of Western and Eastern designs worked, they were adopted.

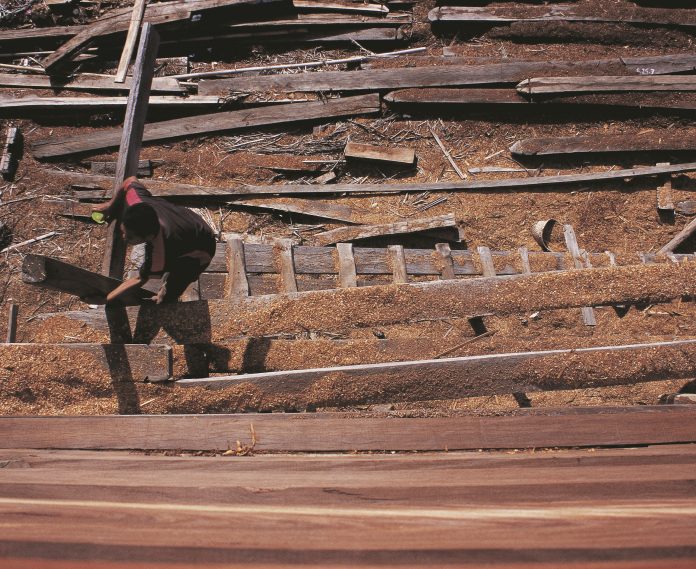

Here in idyllic Tanah Beru, generations of Buginese shipwrights and craftsmen have painstakingly fashioned vessels out of huge blocks of ironwood and teak without any recourse to drawings or plans. Measurements are determined and discussions ensue with the help of a kretek or two – that ubiquitous clove cigarette, itself an icon of Indonesia. Skeletons of boats, their ribbing exposed to the elements, are lined up as if in expectation of the ghostly “Flying Dutchman” taking his pick before embarking on his eternal voyage.

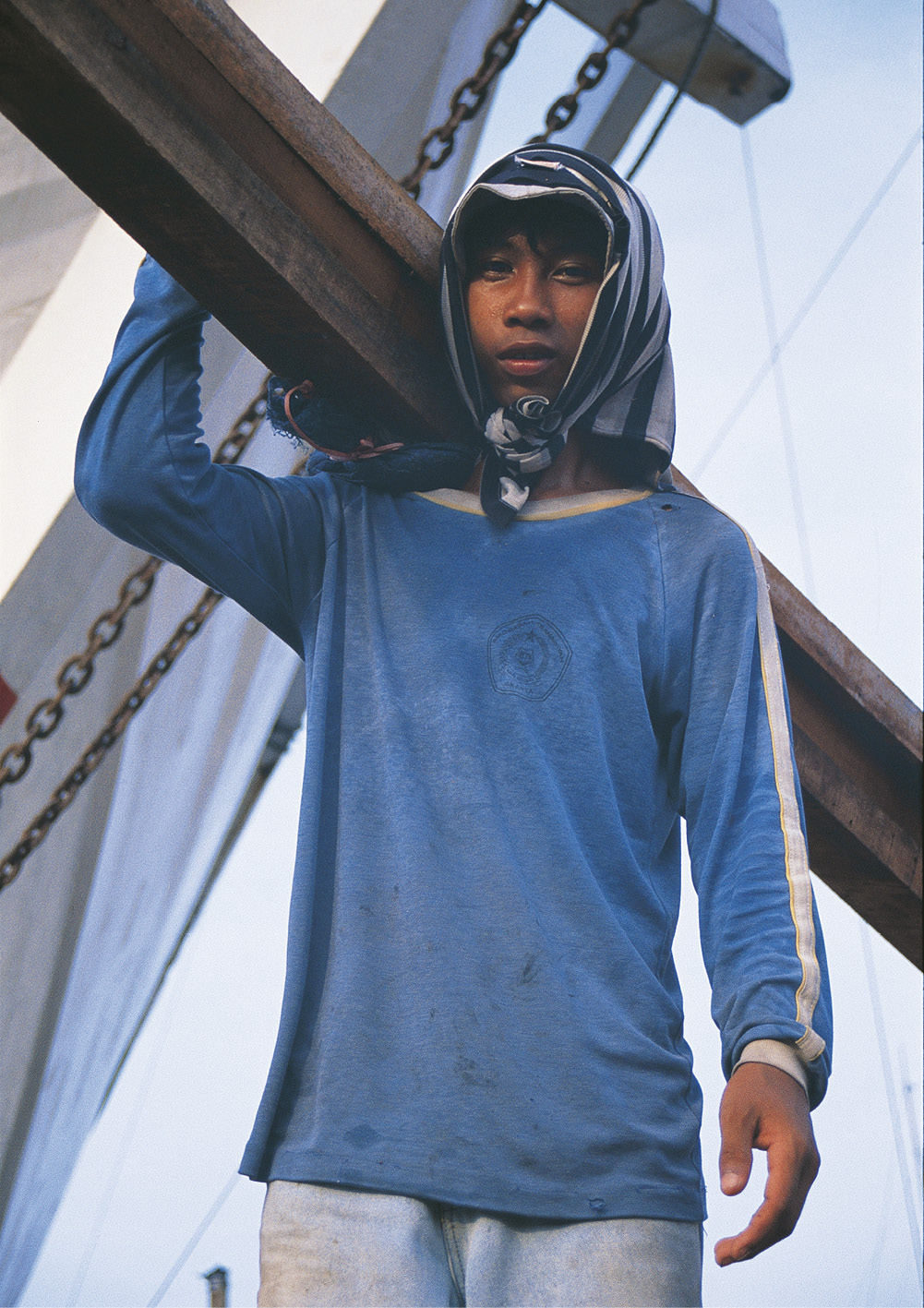

The beach resounds not with the melodious tinkle of the gamelan but the buzz of saws and incessant pounding of hammers ramming in wooden pegs in wooden hulls (though drills and other labour-saving devices have naturally made their mark). Traditions are still part and parcel of Tanah Beru itself. Ritual and ceremony lace every stage of the exacting project of boatbuilding.

“We’ll start work on Wednesday,” pronounces a village elder, except that it’s no ordinary Wednesday but the first Wednesday of an Islamic month. On that day, five or seven men enter the forest to choose the timber. Addressing the spirits of the forest, the chief shipwright notifies them of the men’s intention to fell a tree before starting on the task of selection. Needless to say, the timber has to be free of infestation and, amongst other requirements, fall in the appropriate direction when cut. It is also imperative that the site selected for building a vessel be ritually cleansed beforehand.

With diminishing forests, and practically no teak and ironwood trees left in South Sulawesi, boatbuilders have to journey to the source of timber, usually Kalimantan, the Indonesian portion of Borneo. That source is rapidly shrinking as well.

Laying the keel is of prime importance as this is the initial act that kicks off the entire construction process. Two ironwood planks form the base of the keel and they are as heavy as their name suggests. The keel measures 17 metres in length and 60 centimetres in width. Within the keel is laid a sacrificial offering of a black goat, doubtless recalling ancient times when human sacrifices were once carried out.

The union of keel and hull serves as a symbol of union between male and female. Tradition dictates that while working on the keel, shipwrights do so under a piece of white cloth; placing within a hole ritualistic objects such as gold, iron and rice. Chicken blood is thereafter smeared on the keel. Their significance is clear: gold for wealth, iron for strength, rice for prosperity and blood serves as purification.

After the keel is laid, planks for the hull are pegged together. Of all the planks, the most important is the bengo, meaning, “confused”. Cut from the first tree, it must be perfectly aligned with the sternpost. Any fault or crack is problematic, as that would cause confusion amongst the crew.

For the rest of this article (Asian Geographic No.78 Issue 1/2011) and other stories, check out our past issues here or download a digital copy here

![The Road to Independence: Malaya’s Battle Against Communism [1948-1960]](https://asiangeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/WhatsApp-Image-2021-07-26-at-11.07.56-AM-218x150.jpeg)