By Khong Swee Lin

“In the territory of Pahang the main places are Hujung and Medini… as well as Kalantěn and Tringgano… Tumasik… The whole region as a group…”

Desawarnana, Canto 14

This epic poem by Prapanca from the court of Hayam Wuruk (r. 1350–1388), ruler of the Majapahit Kingdom of East Java, provides amongst other things, an account of lands under Majapahit influence, including “Tumasik”. Temasek was the landing point of choice for Palembang prince Sang Nila Utama, titled Sri Tri Buana, its first ruler some time in 1299.

The Cape of Stakes

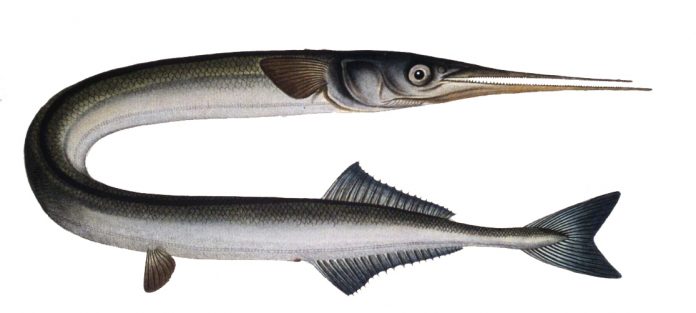

By the time Temasek’s fourth ruler Dam Raja (Sri Maharaja) ascended the throne (r. 1375–1388), Temasek seemed to be a busy trading port. Renamed “Singapura” by Sang Nila Utama, early Singapore was no stranger to unwelcome visitors, having encountered invading Siamese and Majapahit Javanese. This time, however, the predators were piscine. Shoals of garfish (Belone belone) impaled victims with their razor mouths. Even Sri Maharaja was nearly attacked while on an inspection tour atop his elephant.

With lives at stake, Sri Maharaja failed to realise the solution lay in, quite simply, stakes. It took a whiz kid of 11 years to suggest laying a stockade of banana trunks along the affected shoreline thus ensnaring the “built-in” weapons of the fish. The proposal was tested. The garfish arrived on schedule, but were caught off-guard as their mouths got stuck in the pagar (Malay for “fence”) of fleshy trunks. Tanjong Pagar, the Cape of Stakes, was an apt moniker.

Munshi Abdullah, the father of modern Malay literature and interpreter/secretary to Sir Stamford Raffles had a more prosaic explanation. He recorded that fishing stakes, or kelong, had been set up in the area. The Malay term kelong is very familiar to many Singaporeans who go fishing in the waters near the island, overnighting on the kelong, or fish traps.

“Strait-Through”

“The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things…

Of dragon’s teeth and sailing ships.

Of corsairs and kings…”

Lewis Carroll

In the olden times (or as the Malay language puts it poetically, di zaman dahulu), Singapore could have been “Sabana”, an “emporium” depicted on a map by Greek astronomer/cartographer Klaudios Ptolemy, located at the tip of the Malay Peninsula known to the Greeks as “The Golden Chersonese” in the mid-second century BC.

Few realised Tanjong Pagar was blessed with sheltered waters and a deep-water harbour, least of all a certain gentleman whose statue adorns a prominent part of this island. It was his Resident, William Farquhar, who informed Stamford Raffles of the existence of a (new) harbour in September 1819, now called Keppel Harbour.

Present-day Labrador Jetty could have provided a view of dragon’s teeth. In his 1349 journal, Daoyi Zhilue, intrepid Chinese traveller and trader Wang Dayuan describes the area as “Longyamen” (meaning “Dragon’s Tooth Gate”, and also known as “Dragon’s Teeth Straits”), alluding to two granite outcrops akin to dragon’s teeth and also to the term “dragon’s teeth” for pegs at the bows of Chinese junks. He writes, “[T]he Strait runs between the two hills of the Danmaxi (Temasek [?]) barbarians, which look like dragon’s teeth. Through the centre runs a waterway…” Obstacles to the entrance of Singapore’s new harbour, the rocks were blown up in 1848 by J.T. Thomson, Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements (1840–1855).

From the late 15th century, Portuguese ships began to probe Southeast Asian waters, portentously mugging Malacca in 1511. Besides “establishing” trading networks in major Southeast Asian ports, the Portuguese introduced a Western writing system, a new language, and Christianity.

Enter Manoel Godinho de Erédia (born to a Portuguese officer and Buginese princess), a cartographer and mathematician who charted a map of Singapore and its straits. His 1604 “chorographic description of the Straits of Sincapura” shows a passage past Tanjong Pagar marked as Estreito Velho, or Old Straits.

The “Battle” of Tanjong Pagar

In the tussle over control of maritime passages around the island, the Portuguese would not comply with the insistence of the Johore Sultan that Portuguese vessels sail through the Johore Straits instead of using the Old Straits. In retaliation, Sultan Ali Jalla decided in 1586 to launch an attack by sinking several galleys and blocking the harbour entrance, thus forcing the Portuguese to search for another route.

With the help of their trusty “batins”, or local pilots, known as orang laut, or “sea people” (corsairs to the Portuguese), they found another route to the south, naming it the “Santa Barbara Channel”, or “New Straits”. The orang laut were thus the original inhabitants of Tanjong Pagar.

Pulling the brakes: The final whistle at the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station

“When a train pulls into a great city I am reminded of the closing moments of an overture.”

(Henry) Grahame Green (1904–91), Travels with My Aunt (1969)

Passengers laden with assorted belongings scurry across the platform. From her black-and-white Spottiswoode Park home, Alice witnesses the nightly platform hustle

and bustle.

It is after nine in the evening. The night mail to Kuala Lumpur departs soon. Outside, the Greek-style statues stand proudly beneath the emblem “FMSR” – the Federated Malay States Railways – the crucial link allowing these economic pillars of agriculture, transport, industry and commerce to thrive. Inside, murals depict rubber growing, tin mining and other hallmarks of Malayan commercial life.

Enjoying their last sips of teh tarik (local “pulled” tea) or kopi (local coffee) at the station stalls, passengers reluctantly begin to board whilst the stationmaster checks the key token for the next stop, a traditional method permitting train drivers to proceed, dating from 1885.

Repair and maintenance sheds away from the hubbub have been busy looking after essential parts of this vital transport system. Domestic activities in little homes alongside the tracks give a “village” atmosphere to the august Tanjong Pagar Railway Station, designed in 1932 by D.S. Petrovich of Swan & McLaren Architects, with iconic art-deco style façade and station clock. Upper floors once housed the Station Hotel – shades of brass-buttoned white tunics, G&Ts and “tiffin”?

The night mail from Kuala Lumpur returns to Singapore next morning, halting briefly at the charming country station “Bukit Timah”, surrounded by kilometres of tumbling verdure, something rarely seen in urban Singapore. The stationmaster manually pulls the signal lever before the train arrives or departs and prepares the key token. It is signal lever No. 21, the “Raja” (Malay for “King”) of all levers, that is eventually pulled.

July 1, 2011. Alice’s fine black-and-white bungalow with train view was indiscriminately torn down years ago. The station has closed, its successor operating at Woodlands. The KTMB, the Keratapi Tanah Melayu (Malaysian Railways) and successor of the FMSR, left in style with the Sultan of Johor driving a special locomotive on June 30, 2011, leaving a heavy trail of nostalgia and a whole gamut of human emotion in its wake.

Dr Lai Chee Kien of the Faculty of Architecture, National University of Singapore, notes that the connection and relations between Singapore and Malaysia go beyond politics: “[W]e have economic, geographical, historical and social ties…”. Indeed, some of our forefathers travelled by

rail from Malaya to build a new life in Singapore, as did the writer’s father and grandparents.

These ties and beginnings could not have been created without the existence of this humble railway and its stations, big or small.

For more stories and photos, check out Asian Geographic Issue 113.

![The Road to Independence: Malaya’s Battle Against Communism [1948-1960]](https://asiangeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/WhatsApp-Image-2021-07-26-at-11.07.56-AM-218x150.jpeg)