Explore the rich history of Zorostrianism — the world’s first monotheistic faith

Text Sophie Ibbotson

Adam and Eve, if they existed, would have known God in the wonder of the natural world, the earth, the air, and water. Jesus Christ was not a Christian, but a Jew, and he knew better than anyone that God is multifaceted. Although Jewish scholars and theologians name Abraham as the first Jew because he rejected idolatry and recognised one god, the concept of monotheism – which passed from Jews to Christians, and then to Muslims, too – was not something new. Abraham just happened to be the man who made it famous, and whom popular history has recorded as the originator, the first believer.

But before Abraham, and what we know as the three Abrahamic faiths, there were already those who worshipped one god: the Zoroastrians, or Parsis, as many of the modern-day adherents of the religion are known. A small community, who traditionally marry amongst themselves and have no doctrinal requirement to proselytise, their history and the tenets of their faith are poorly understood by outsiders. But the impact of their ideas over the past 3,000 years has been nothing short of revolutionary. Zoroastrianism transformed the dominant belief systems from the polytheistic worship of gods representing natural phenomenon, and Mother Earth figures representing fertility and harvest, to the conceptualisation and worship of a single, male god.

The prehistoric roots of Zoroastrianism are to be found in northern Iran, and what is now Azerbaijan, in the early second millennium BC. The faiths of Indo-Iranian peoples at this time typically focused on cosmic mythology, and groups of deities embodying (for example) water and rivers, the sun, spirits, and primordial serpents or dragons. These religious beliefs and rites were closely related to those of Vedism, the forerunner to Hinduism in India; during this early period, there was undoubtedly a cross-fertilisation of concepts between India and Iran.

The ancient prophet credited with amalgamating these numerous deities into a single, umbrella god was Zoroaster, or Zarathustra, as he would have been in the Avestan language. There is no consensus amongst scholars as to when exactly he lived, but the respected philologist Mary Boyce, who was until her death in 2006 the foremost authority on Zoroastrianism, suggests he may have been born as early as 1,700 BC.

Certainly, Zoroastrianism was already long-established when it became a significant religion of the Medes in the 8th century BC, and the official religion of the Achaemenid Empire 200 years later.

Zoroastrian beliefs

The ideas which Zoroaster espoused did not materialise out of the blue: It is likely that many of the concepts attributed to him were already gaining currency in society at the time. Zoroaster was a reformer, able to refine and communicate those ideas in a way which was accessible to the masses.

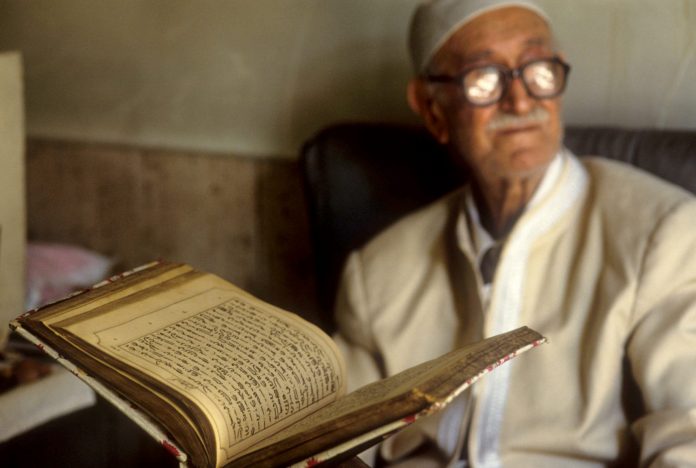

The sacred text of the Zoroastrians, the Avesta (“Book of the Law”), a fragmentary collection of sacred writings compiled over many centuries, includes the Gathas, hymns of praise ascribed to Zoroaster, but also invocations and rituals, spells against demons, and prescriptions for purification. These types of materials would have been commonplace across the ancient world, but Zoroaster and his followers changed their focus. Zoroaster’s single most important theological concept is that of dualism: that two opposites co-exist.

The creator god is Ahura Mazda, the lord or spirit of wisdom. He alone should be invoked and worshipped, because he is the highest power of all, and it is he who sustains the world. The name Ahura Mazda was attributed to an ancient Iranian spirit prior to the birth of Zoroaster, but it was Zoroaster who proclaimed him to be an “uncreated spirit”. This placed him as present before the beginning of the world, positioning Ahura Mazda as the ultimate creator of all things.

This revelation was revealed to Zoroaster in a vision. At the age of 30, Zoroaster was led into the presence of Ahura Mazda, taught the cardinal principles of Zoroastrianism, and thenceforth felt that he was divinely appointed to preach what he had learned.

Ahura Mazda was designated the supreme being, or God. But in a dualistic universe, Ahura Mazda must, of course, have an opposite, and that is Angra Mainyu, a destructive spirit akin to the devil, or a demon. Angra Mainyu is not Ahura Mazda’s equal – how could he be? – but nevertheless, he and his hostile force of daevas (evil spirits) attempt to distract humankind from the path of righteousness.

For Zoroastrians, Ahura Mazda represents the truth, and that which is good; and Angra Mainyu is the embodiment of evil (moving away from truth and goodness). Humankind has free will – we are not the playthings of an immortal – and so we must choose of our own volition which path we will follow. The decisions we make are of cosmic importance, and affect our eternal destiny. People whose good deeds in life outweigh their wrongdoings will be taken into “heaven” – the abode of Ahura Mazda – when they die, but “hell” awaits those whose balance of thoughts and actions tend towards the wicked.

When we commit sin, it is our responsibility to repent, confess our sins to a priest, and resolve not to sin again. But even doing this, and purifying ourselves with sacred recitations, fasting, or conducting ceremonies around a sacred fire, our sins remain. We cannot undo our previous thoughts, words, and actions, but carry them with us, even in death. It is for this reason that Zoroastrians have very particular funeral rites: Burying the body would pollute the soil; cremating it would pollute the air. The corpse is therefore taken to Dakhmeh-ye Zartoshtiyu – “the Tower of Silence” – and exposed there, naked. Vultures come to strip the bones, which, once dried by the sun, can then be collected and placed in an ossuary.

We can appreciate, then, some core tenets of the later monotheistic religions already emerging in Zoroastrian theology: There is a single god juxtaposed with the devil; good is pitted against evil, heaven against hell. It is the ethics of our thoughts, words, and deeds as individuals which will dictate the outcome for us in the afterlife. We must repent our sins and purify our bodies, but recognise that we are forever impure. Significantly, we have the right and ability to choose, even if Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu and his daevas seek to influence our decisions.

Impact on World Religions

Today, it is estimated that there are fewer than 190,000 Zoroastrians worldwide, with the major populations located in India, Iran and Iraq, with some in Central Asia and the US. They are typically of Iranian origin, and referred to as Parsis. The population appears to be shrinking due to low birth rates, marriage with non-Zoroastrians, and migration into communities where Zoroastrianism isn’t practised. However, that is not to say that the legacy of Zoroastrianism is dying; in fact, it is stronger than ever.

Zoroastrianism was the official religion of the Achaemenid Empire, which stretched from Bulgaria and Romania in the west, across Egypt and the Middle East, through Persia and the Caucasus to Russia, and east through Afghanistan to what is now the heart of Pakistan. There was a mass migration of Zoroastrians to India in the 8th century AD, and subsequent waves of migration to South and Central Asia. This movement of people, and their faith, meant that the core concepts of Zoroastrianism were widely heard, discussed, and gained credibility, especially in the commercial and intellectual centres of the time.

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam were all conceived, born, and developed in their early years in the same intellectual and cultural sphere: the Middle East. Zoroastrianism had already sown its seeds in this fertile ground, and these bore fruit as these Abrahamic faiths flourished, propagating Zoroastrianism’s most crucial ideas. But this was not the only way in which these faiths would entwine with their forefather.

In the Christmas story, you’ll recall that three wise men came from the east – probably from Persia – to visit the infant Jesus. They’re often referred to as the magi. The term “magi” has been used since at least the 6th century BC to denote Zoroastrian priests. They were known in the ancient world for their study of astrology, and they believed that the appearance of certain stars heralded the birth of rulers. What is more, the earliest surviving depiction of the magi, a 6th century AD mosaic in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, shows three pale-skinned men wearing distinctive red Phrygian caps, and pointed shoes. These items were the traditional garb of the Zoroastrian priests, suggesting that the artisans who made the mosaic accepted that identity.

Today, the Zoroastrian population has dispersed, and many of their temples lie in ruin, their places of worship and their theology replaced by those of newer faiths. But with monotheists now numbering an estimated 55 percent of the world’s population, their beliefs directly descended from those of Zoroaster, the significance of its impact is incontestable.

For more stories and photos, check out Asian Geographic Issue 122.

![The Road to Independence: Malaya’s Battle Against Communism [1948-1960]](https://asiangeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/WhatsApp-Image-2021-07-26-at-11.07.56-AM-218x150.jpeg)