By Khong Swee Lin

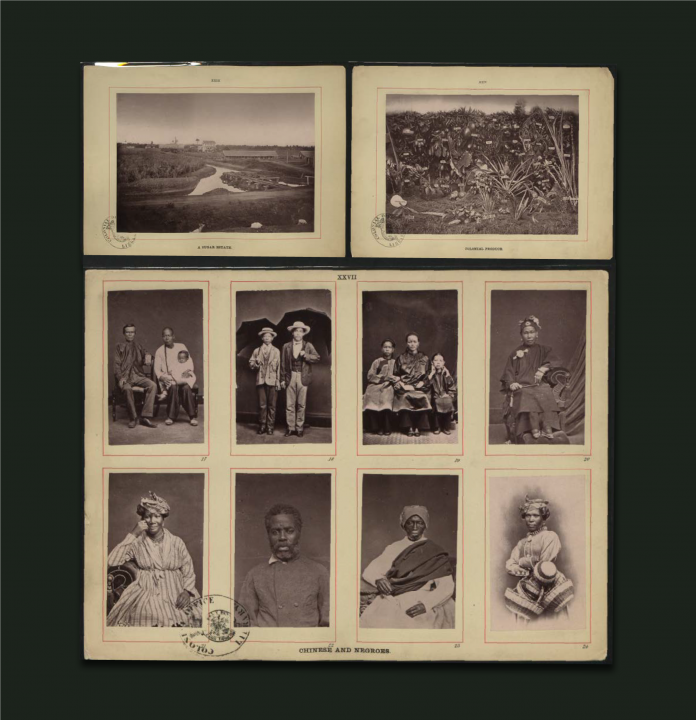

The Abundant Delta

Sometime in 1859, 20-year-old Fung A Pan, a native of Poon Ye in the heart of the Pearl River Delta, left home. The little county of Poon Ye, so named in the Cantonese dialect, but called Pan Yu in Mandarin, was once one of the oldest cities in China. Dating back to 214 BC, it was conquered by none other than Qin Shi Huang, China’s first Emperor who thereafter established it as the capital of Nanyue around 206 BC. It held the honour of being a prosperous commercial centre as apparently Arab and Southeast Asian artefacts were found there. It was also the former name of Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong.

Saccharum Officinarum L., or hybrids of the species, more commonly known as sugarcane, was not only a major crop of the Pearl River Delta, but a symbol of protection and prosperity to some Southern Chinese. The finality of leaving home was especially poignant to young pedlar, Fung as he was never to set foot again in his ancestral home. Sugarcane, which he was well acquainted with, was to dominate his new life in a totally unfamiliar setting, thousands of miles away from the familiar Delta area.

Sailing Abroad

On Christmas Eve in 1859, Fung boarded the clipper ship “Whirlwind” from Hong Kong. He was paid an advance of eight Spanish dollars (out of which two Spanish dollars were to be paid to his parents in Poon Ye). The 78-day journey of roughly 16,897 kilometres or 9123.65011 nautical miles, ended on 11 March 1860 after stops at Singapore and Cape Town with disembarkation at British Guiana’s capital, Georgetown. A perusal of the Chinese Register and the National Archives of Guyana clearly showed that Fung went to work in the sugar plantations of British Guiana.

“The reed that produces honey without bees”, as the ancient Persians and Greeks described sugarcane, was introduced into Guyana by Dutch settlers with plants from the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch West Indies Company imported African slaves to deal with labour shortages and the British, who gained control of the country in 1814, did likewise. Demand for sugar meant enormous profits for the sugar trade and the colony was developed solely for that purpose.

However, change was in the air. Growing Western sentiment against the inhumane slave trade began to affect European colonial powers. So having no choice but to urgently turn to other sources of labour for their plantations, the colonial masters recruited workers from other countries.

The Chinese Coolie Trade

A look at the island of Penang in Malaysia convinced them to consider the import of Chinese labourers. Trev Sue-A-Quan’s quintessential book Cane Reapers cites a letter written by a planter to the West India Committee (the body representing the region’s business interests in Britain) in May 1843, following a trip made to Singapore, Malacca and Penang to observe Chinese labourers at work:

“At Prince of Wales Isle in Penang there are 2,000 acres of land cultivated exclusively by them; (Chinese labourers), and during the heat of the day, I have seen them cutting canes… And I can state, without hesitation going through all the work as well as the best picked men (Creoles) would do…. nowhere I have seen a people who would suit us and our purposes better.”

In order to escape growing lawlessness, famine and strife, many South Chinese left via nearby ports, and so the coolie trade evolved. The term “coolie” is believed to have came from the Chinese word “ku”, meaning bitter, as emigration of this nature was anything but sweet. Although labourers could be categorised as “free” or “contract”(i.e. “indentured”), it was the latter system that kept profits rolling in for Caribbean sugar plantations, often at great personal cost to the labourer.

A contract of indenture for an initial term of five years was not foolproof. Signed before the vessel set sail, contracts could be torn up by the ship’s captain once it reached international waters, or underhandedly “substituted” with onerous terms or even sold to other parties upon arrival. Those heading for Cuba and Peru could be greeted with the unwelcome surprise of being sold into slavery. Naturally, luck played a part.

Transitions and Transplants

Fortunately for Fung A Pan, his vessel “The Whirlwind” was true to name and made a quick run of only 78 days. Not only was it a propitious journey, all 372 passengers remained alive and in good health. On arrival at Georgetown, Fung was sent to Plantation Montrose east of the Demerara River.

Plantation life was tough as expected, and as the Chinese were not homogeneous, living and working in a strange land with unfamiliar “compatriots” of differing dialects would have exacerbated conditions all the more. Many complaints revolved around food, especially the insufficient supply and steep price of rice and new arrivals were often in trouble with the law for stealing food.

Stated to be a mere five feet two inches in height, Fung A Pan must have been of sturdy stock to withstand two terms of indenture. There, he married Yung Shee who was not indentured as she had travelled on the “Claramont” as wife of Chow-A-Ming, an interpreter. She was separated from him some time thereafter. Marriages of convenience prior to boarding were common as a bounty of 20 Spanish dollars would be given to a married man, though many were never paid.

By the time Fung A Pan and Yung Shee were baptised at the Chinese community’s St Saviour’s Church in 1879, taking the names “Jacob” and “Abigail” respectively, they were already building a family. Nine of 11 children made it to adulthood – Philip (b.1863), Isaac (Teen-Yong, b.1868), Mary Jane (Aliku), Frederick (A-Yow), Abraham (A-Choi), Joseph (Wallah, b.1877), William (Masha), Jacob (Apaca, b.1875) and Cecilia (Yuku, b.1882).

It is interesting to note Andrew Fung’s observations on the naming of Fung A Pan’s children. Andrew is a present-day descendant of Isaac’s eldest son, Samuel who lives in Singapore today. He mentions that in the Biblical story, “Isaac begat Jacob” but in the Fung family it was the other way round. If anything, it showed the increasing Western and Christian influences within the Chinese community not only in British Guiana, but also in South China, thanks to the efforts of missionaries like Wilhelm Lobscheid and Hudson Taylor.

More Bitter than Sweet

Post-indenture, Fung A Pan could have returned to China with a token sum of 50 Spanish dollars, but few took up this stingy offer. Entrepreneurship was key to survival and provision shops on plantations were opened by many Chinese supplying rice, necessities and alcohol. Fung A Pan, now known as Jacob, followed the trend with four shops between 1880–1886. His son, Isaac was also involved in the businesses.

However, in 1886, a case of bad timing in the formation of a partnership led to the eventual insolvency of Jacob. His wife, Abigail, while going about her shopping one day accompanied by her granddaughter, was fatally stabbed in the neck by Jacob’s ex-employee later declared insane. The full story of this tragedy may be found in Laura Hall’s paper, “Debt and Death in British Guiana”. Laura is a descendant of Isaac and Mary, through her mother, Phyllis Lee. Isaac, on the other hand proved to be adept in business and made a name for himself in cocoa in the district of Essequibo. Cocoa became a popular crop, with local demand termed “steady”.

Isaac and his wife Mary Chin-A-Yun had 10 children, the eldest son Samuel born in 1890. Samuel’s birth was significant, for the boy was to uproot himself just as his grandfather left Poon Ye to establish himself in a foreign land. The Chinese community have always emphasised the importance of education, and a parent’s dearest wish would be fulfilled if a child attained a higher level of education than the parent. In Samuel Fung’s case, off he went to London to read law at the Middle Temple, but nobody could have anticipated the outcome.

In Grandfather’s Footsteps

After his call to the Bar in 1913, Samuel returned home to practice law before travelling to the Crown Colony of Penang ostensibly for a holiday in 1919. For Samuel, the trip would have echoed that of his forefather in looking for greener pastures. The unexpected happened and he married Miss Cheah Phaik Har from a prominent Penang Hokkien family in 1920.

Samuel was one of the first few Chinese lawyers to qualify in the UK. An entry in a list of Malayan law firms established prior to independence states “Samuel Fung – Penang & Batu Pahat (1910s–1930s)”. By 1929, he had settled in Singapore. Although Samuel and his family moved to Singapore, their five children Eddie (b.1922), Kismet (b.1923), William (b.1925), George (b.1927) and Kathie (b.1928) were all Penang-born. Life was peaceful until the storm clouds of the second world war gathered on the horizon, for life was never going to be the same again.

As the island of Singapore fell to Japanese invaders, Chinese men were being rounded up and summarily executed by Japanese military as part of the Sook Ching Massacre from February to March 1942. Samuel was not hauled up then, but subsequently received the dreaded “summons” to report to the Japanese Kempetai at the infamous YMCA building. He was never seen again. His wife Phaik Har passed away in 1943 from diabetes.

Certainly the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–1945) was just as much a time of testing for Samuel’s children as it was for Jacob almost a century ago upon losing his wife Abigail. Resilience and definitely fortitude were two necessary traits of the Fung psyche that surfaced to enable the families not only to survive but to build on for the future. Samuel’s sons, the Fung brothers, Eddie, William and George explored many wartime ventures including “Kill-Em”, a kerosene-based insect repellent spray.

Samuel’s decisions to journey to Penang and to lay down roots in the Straits Settlements was one that changed their family history. The Southeast Asian branch of the Fung diaspora as represented by the descendants of Samuel now boasts 24 grandchildren, 45 great grandchildren and one great-great grandchild. In the post-war era, Samuel’s five children contributed in many ways to Singapore.

The Land of Waters

The name Guyana as spelt today means “Land of Waters” in the indigenous Amerindian language. Guyana is water-rich, and its uses are many. Water fed sugarcane fields, water symbolises wealth in Feng Shui, ships travelled on water to bring men to the plantations and men relied on water for their livelihoods, whether for crop planting, gold-panning, rum-making or laundry-running.

Within this land, the sugarcane grass was once king. As men toiled to satisfy its great thirst, hurt by its sharp blades shielding its prized yield, they stoically and resolutely helped to build a society and an economy. Many of their descendants are now scattered far and wide, across waters, dispersed as if by the wind that pollinates the sugarcane’s inflorescence. The sugarcane reapers of the early 19th century contributed in no small measure to their communities and countries just as Fung A Pan surely did.

For more stories and photos, check out Asian Geographic Issue 119.

![The Road to Independence: Malaya’s Battle Against Communism [1948-1960]](https://asiangeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/WhatsApp-Image-2021-07-26-at-11.07.56-AM-218x150.jpeg)