text SHAILENDRA BHANDARE

photos ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

AS everyone knows from the old English adage, the answer to the title of this tale is money. It comes to us in its three most ubiquitous forms – coins, banknotes and cards, or “plastic” – and we use it to make payments. That remains the most simplistic definition of “money”, but almost anything that can be used to make a payment can be money. Indeed, societies across the globe used various objects as money in different sorts of circumstances. People on the island of Yap in the Caroline Islands group (Micronesia) used doughnut-shaped stones as money. During World War I, the French used postage stamps enclosed in tin casing as money. Even today, simple objects like mints and candy assume the role of money from time to time in certain countries to alleviate the shortfall of a more familiar form of money, metallic coins.

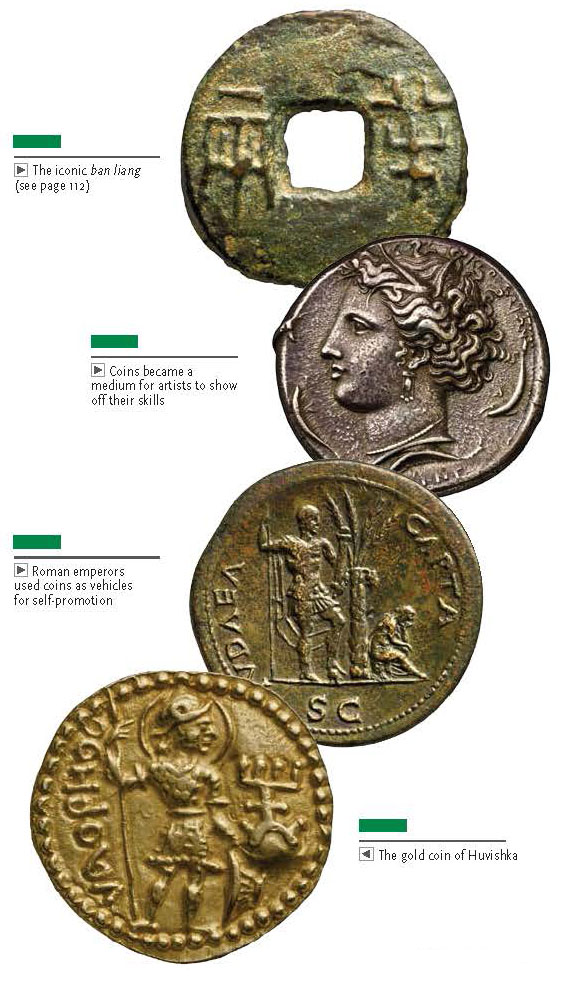

Coins were “invented” as a form of money in about the seventh century BC, but metal, as a medium of exchange, goes back much further. We have references from the earliest civilisations such as the Babylonian where pre-weighed metal functioned as money in the form of bars, ingots, wire and plate. Indeed, the Babylonians had already developed the concepts of credit, debt and interest in the third millennium BC. What sets coins apart from simple metal being used as “money” is the stamp of authority that they bear. The stamp vouches for the weight and purity of the metal and thus increases its scope of acceptance as payment to a “universal” level. Anyone who trusts in the authority could be rest assured that a product certified by it could be safely used in transactions.

The earliest coins date to about 650 BC and come from Asia Minor (western Turkey), a region that belonged to the classical Greek world at the time and was known as Lydia. Lydian coins are made of a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver called electrum and bear the dies that carry negative impressions of the motifs appearing on coins. When a piece of metal is stamped either by or between such devices, these impressions are transferred onto the metal, giving us a “coin”.

The idea of coins appears to have been simultaneously invented in other parts of Asia too. By 500 to 450 BC, coinage had been firmly established in India. Precisely how early Indian coins can be dated has been a matter of some debate, particularly because we do not have corroborative archaeological data to support their inception. But the Indian coinage tradition remains different from its Greek counterpart in being almost exclusively of silver and manufactured using multiple dies having small symbols,thereby having a “punch-marked” appearance. Indian coinage is based on indigenous weight standards, although Persian influence in the choice of weight is apparent in some cases as well.

In China, we have a slightly different picture. Evidence suggests that metallic objects were being used in China much earlier than the seventh century BC, during the Zhou Dynasty, but their forms were very different. In some cases, they evolved from the practice of cowry shells being used as money; in their metallic form, therefore, they resembled cowries as well. In other instances, their precursors were agricultural implements that were exchanged in transactions. Objects in the shape of spades and knives are thus the most well known amongst earliest Chinese “coins”. Chinese coins stand apart from Greek and Indian coins in being made exclusively of bronze and manufactured by casting from molten metal. The use of coins of different shapes came to an end after the unification of China under Qin Shih Huang-Di in 221 BC. He introduced a uniform currency throughout his empire composed of circular coins with a square hole in the centre, and called it the ban liang.

Check out the rest of this article in Asian Geographic No.88 Issue 3/2012 here or download a digital copy here

![The Road to Independence: Malaya’s Battle Against Communism [1948-1960]](https://asiangeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/WhatsApp-Image-2021-07-26-at-11.07.56-AM-218x150.jpeg)